“Blood grows hot, and blood is spilled. Thought is forced from old channels into confusion. Deception breeds and thrives. Confidence dies, and universal suspicion reigns. Each man feels an impulse to kill his neighbor, lest he be first killed by him. Revenge and retaliation follow. And all this … may be among honest men only. But this is not all. Every foul bird comes abroad, and every dirty reptile rises up. These add crime to confusion.”

— Abraham Lincoln, letter to the Missouri abolitionist Charles D. Drake, 1863

I. ON THE BRINK

In the weeks before Labor Day 2020, Ted Wheeler, the mayor of Portland, Oregon, began warning people that he believed someone would soon be killed by extremists in his city. Portland was preparing for the 100th consecutive day of conflict among anti-police protesters, right-wing counterprotesters, and the police themselves. Night after night, hundreds of people clashed in the streets. They attacked one another with baseball bats, Tasers, bear spray, fireworks. They filled balloons with urine and marbles and fired them at police officers with slingshots. The police lobbed flash-bang grenades. One man shot another in the eye with a paintball gun and pointed a loaded revolver at a screaming crowd. The FBI notified the public of a bomb threat against federal buildings in the city. Several homemade bombs were hurled into a group of people in a city park.

Extremists on the left and on the right, each side inhabiting its own reality, had come to own a portion of downtown Portland. These radicals acted without restraint or, in many cases, humanity.

In early July, when then-President Donald Trump deployed federal law-enforcement agents in tactical gear to Portland—against the wishes of the mayor and the governor—conditions deteriorated further. Agents threw protesters into unmarked vans. A federal officer shot a man in the forehead with a nonlethal munition, fracturing his skull. The authorities used chemical agents on crowds so frequently that even Mayor Wheeler found himself caught in clouds of tear gas. People set fires. They threw rocks and Molotov cocktails. They swung hammers into windows. Then, on the last Saturday of August, a 600-vehicle caravan of Trump supporters rode into Portland waving American flags and Trump flags with slogans like TAKE AMERICA BACK and MAKE LIBERALS CRY AGAIN. Within hours, a 39-year-old man would be dead—shot in the chest by a self-described anti-fascist. Five days later, federal agents killed the suspect—in self-defense, the government claimed—during a confrontation in Washington State.

What had seemed from the outside to be spontaneous protests centered on the murder of George Floyd were in fact the culmination of a long-standing ideological battle. Some four years earlier, Trump supporters had identified Portland, correctly, as an ideal place to provoke the left. The city is often mocked for its infatuation with leftist ideas and performative politics. That reputation, lampooned in the television series Portlandia, is not completely unwarranted. Right-wing extremists understood that Portland’s reaction to a trolling campaign would be swift, and would guarantee the celebrity that comes with virality. When Trump won the presidency, this dynamic intensified, and Portland became a place where radicals would go to brawl in the streets. By the middle of 2018, far-right groups such as the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer had hosted more than a dozen rallies in the Pacific Northwest, many of them in Portland. Then, in 2020, extremists on the left hijacked largely peaceful anti-police protests with their own violent tactics, and right-wing radicals saw an opening for a major fight.

What happened in Portland, like what happened in Washington, D.C., on January 6, 2021, was a concentrated manifestation of the political violence that is all around us now. By political violence, I mean acts of violence intended to achieve political goals, whether driven by ideological vision or by delusions and hatred. More Americans are bringing weapons to political protests. Openly white-supremacist activity rose more than twelvefold from 2017 to 2021. Political aggression today is often expressed in the violent rhetoric of war. People build their political identities not around shared values but around a hatred for their foes, a phenomenon known as “negative partisanship.” A growing number of elected officials face harassment and death threats, causing many to leave politics. By nearly every measure, political violence is seen as more acceptable today than it was five years ago. A 2022 UC Davis poll found that one in five Americans believes political violence would be “at least sometimes” justified, and one in 10 believes it would be justified if it meant returning Trump to the presidency. Officials at the highest levels of the military and in the White House believe that the United States will see an increase in violent attacks as the 2024 presidential election draws nearer.

In recent years, Americans have contemplated a worst-case scenario, in which the country’s extreme and widening divisions lead to a second Civil War. But what the country is experiencing now—and will likely continue to experience for a generation or more—is something different. The form of extremism we face is a new phase of domestic terror, one characterized by radicalized individuals with shape-shifting ideologies willing to kill their political enemies. Unchecked, it promises an era of slow-motion anarchy.

Consider recent events. In October 2020, authorities arrested more than a dozen men in Michigan, many of them with ties to a paramilitary group. They were in the final stages of a plan to kidnap the state’s Democratic governor, Gretchen Whitmer, and possessed nearly 2,000 rounds of ammunition and hundreds of guns, as well as silencers, improvised explosive devices, and artillery shells. In January 2021, of course, thousands of Trump partisans stormed the U.S. Capitol, some of them armed, chanting “Where’s Nancy?” and “Hang Mike Pence!” Since then, the headlines have gotten smaller—or perhaps numbness has set in—but the violence has continued. In June 2022, a man with a gun and a knife who allegedly said he intended to kill Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh was arrested outside Kavanaugh’s Maryland home. In July, a man with a loaded pistol was arrested outside the home of Pramila Jayapal, the leader of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. She had heard someone outside shouting “Fuck you, cunt!” and “Commie bitch!” Days later, a man with a sharp object jumped onto a stage in upstate New York and allegedly tried to attack another member of Congress, the Republican candidate for governor. In August, just after the seizure of documents from Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home, a man wearing body armor tried to breach the FBI’s Cincinnati field office. He was killed in a shoot-out with police. In October, in San Francisco, a man broke into the home of Nancy Pelosi, then the speaker of the House, and attacked her 82-year-old husband with a hammer, fracturing his skull. In January 2023, a failed Republican candidate for state office in New Mexico who referred to himself as a “MAGA king” was arrested for the alleged attempted murder of local Democratic officials in four separate shootings. In one of the shootings, three bullets passed through the bedroom of a state senator’s 10-year-old daughter as she slept.

Experts I interviewed told me they worry about political violence in broad regions of the country—the Great Lakes, the rural West, the Pacific Northwest, the South. These are places where extremist groups have already emerged, militias are popular, gun culture is thriving, and hard-core partisans collide during close elections in politically consequential states. Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Georgia all came up again and again.

For the past three years, I’ve been preoccupied with a question: How can America survive a period of mass delusion, deep division, and political violence without seeing the permanent dissolution of the ties that bind us? I went looking for moments in history, in the United States and elsewhere, when society has found itself on the brink—or already in the abyss. I learned how cultures have managed to endure sustained political violence, and how they ultimately emerged with democracy still intact.

Some lessons are unhappy ones. Societies tend to ignore the obvious warning signs of endemic political violence until the situation is beyond containment, and violence takes on a life of its own. Government can respond to political violence in brutal ways that undermine democratic values. Worst of all: National leaders, as we see today in an entire political party, can become complicit in political violence and seek to harness it for their own ends.

II. SALAD-BAR EXTREMISM

If you’re looking for a good place to hide an anarchist, you could do worse than Barre, Vermont. Barre (pronounced “berry”) is a small city in the bowl of a steep valley in the northern reaches of a lightly populated, mountainous state. You don’t just stumble upon a place like this.

I went to Barre in October because I wanted to understand the anarchist who had fled there in the early 1900s, at the beginning of a new century already experiencing extraordinary violence and turbulence. The conditions that make a society vulnerable to political violence are complex but well established: highly visible wealth disparity, declining trust in democratic institutions, a perceived sense of victimhood, intense partisan estrangement based on identity, rapid demographic change, flourishing conspiracy theories, violent and dehumanizing rhetoric against the “other,” a sharply divided electorate, and a belief among those who flirt with violence that they can get away with it. All of those conditions were present at the turn of the last century. All of them are present today. Back then, few Americans might have guessed that the violence of that era would rage for decades.

In 1901, an anarchist assassinated President William McKinley—shot him twice in the gut while shaking his hand at the Buffalo World’s Fair. In 1908, an anarchist at a Catholic church in Denver fatally shot the priest who had just given him Communion. In 1910, a dynamite attack on the Los Angeles Times killed 21 people. In 1914, in what officials said was a plot against John D. Rockefeller, a group of anarchists prematurely exploded a bomb in a New York City tenement, killing four people. That same year, extremists set off bombs at two Catholic churches in Manhattan, one of them St. Patrick’s Cathedral. In 1916, an anarchist chef dumped arsenic into the soup at a banquet for politicians, businessmen, and clergy in Chicago; he reportedly used so much that people immediately vomited, which saved their lives. Months later, a shrapnel-filled suitcase bomb killed 10 people and wounded 40 more at a parade in San Francisco. America’s entry into World War I temporarily quelled the violence—among other factors, some anarchists left the country to avoid the draft—but the respite was far from total. In 1917, a bomb exploded inside the Milwaukee Police Department headquarters, killing nine officers and two civilians. In the spring of 1919, dozens of mail bombs were sent to an array of business leaders and government officials, including Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes.

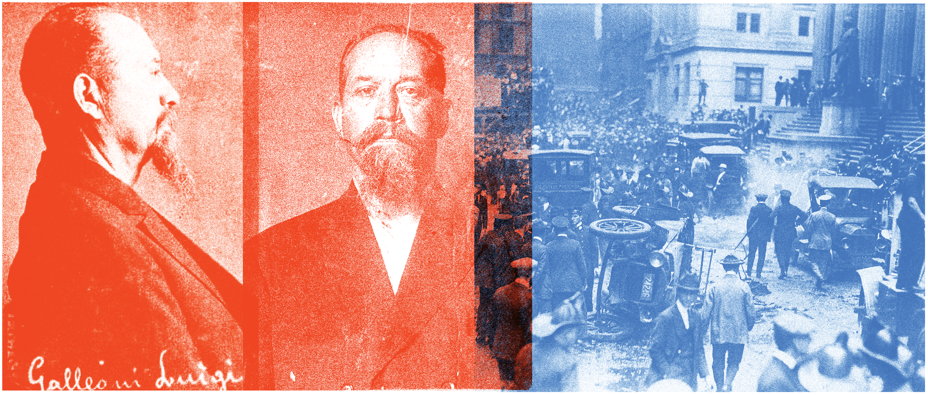

All of this was prologue. Starting late in the evening on June 2, 1919, in a series of coordinated attacks, anarchists simultaneously detonated massive bombs in eight American cities. In Washington, an explosion at the home of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer blasted out the front windows and tore framed photos off the walls. Palmer, in his pajamas, had been reading by his second-story window. He happened to step away minutes before the bomb went off, a decision that authorities believed kept him alive. (His neighbors, the assistant secretary of the Navy and his wife, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, had just gotten home from an evening out when the explosion also shattered their windows. Franklin ran over to Palmer’s house to check on him.) The following year, a horse-drawn carriage drew up to the pink-marble entrance of the J. P. Morgan building on Wall Street and exploded, killing more than 30 people and injuring hundreds more.

From these episodes, one name leaps out across time: Luigi Galleani. Galleani, who was implicated in most of the attacks, is barely remembered today. But he was, in his lifetime, one of the world’s most influential terrorists, famous for advancing the argument for “propaganda of the deed”: the idea that violence is essential to the overthrow of the state and the ruling class. Born in Italy, Galleani immigrated to the United States and spread his views through his anarchist newspaper, Cronaca Sovversiva, or “Subversive Chronicle.” He told the poor to seize property from the rich and urged his followers to arm themselves—to find “a rifle, a dagger, a revolver.”

Galleani fled to Barre in 1903 under the name Luigi Pimpino after several encounters with law enforcement in New Jersey. He attracted disciples—“Galleanisti,” they were called—despite shunning all forms of organization and hierarchy. He was quick-witted, with an imposing intellect and a magnetic manner of speaking. Even the police reports described his charisma.

The population of Barre today is slightly smaller than it was in Galleani’s day—roughly 10,000 then, 8,500 now—and it is the sort of place that is more confused by the presence of strangers than wary of them. The first thing you notice when you arrive is the granite. There is a mausoleum feel to any granite city, and on an overcast day the gray post-office building on North Main Street gives the illusion that all of the color has suddenly vanished from the world. Across the street, at city hall, I wandered into an administrative office where an affable woman—You came to Barre? On purpose?—generously agreed to take me inside the adjacent opera house, which, recently refurbished, looks much as it did on the winter night in 1907 when Galleani appeared there before a packed house to give a speech alongside the anarchist Emma Goldman.

Galleani almost certainly could have disappeared into Barre with his wife and children and gotten away with it. He did not want that. In his own telling, Galleani’s anger was driven by how poorly the working class was treated, particularly in factories. In Barre, granite cutters spent long hours mired in the sludge of a dark, unheated, and poorly ventilated workspace, breathing in silica dust, which made most of them gravely ill. Seeing the town, even a century after Galleani was there, I could understand why his time in Vermont had not altered his worldview. In the foreword to a 2017 biography, Galleani’s grandson, Sean Sayers, put a hagiographic gloss on Galleani’s legacy: “He was not a narrow and callous nihilist; he was a visionary thinker with a beautiful idea of how human society could be—an idea that still resonates today.” For Galleani and other self-identified “communist anarchists” like him, the beautiful idea was a world without government, without laws, without property. Other anarchists did not share his idealism. The movement was torn by disagreements—they were anarchists, after all.

In Galleani’s day, as in our own, the lines of conflict were not cleanly delineated. American radicalism can be a messy stew of ideas and motivations. Violence doesn’t need a clear or consistent ideology and often borrows from several. Federal law-enforcement officials use the term salad-bar extremism to describe what worries them most today, and it applies just as aptly to the extremism of a century ago.

When Galleani had arrived in America, he’d encountered a nation in a terrible mood, one that would feel familiar to us today. Galleani’s children were born into violent times. The nation was divided not least over the cause of its divisions. The gap between rich and poor was colossal—the top 1 percent of Americans possessed almost as much wealth as the rest of the country combined. The population was changing rapidly. Reconstruction had been defeated, and southern states in particular remained horrifically violent toward Black people, for whom the threat of lynching was constant. The Great Migration was just beginning. Immigration surged, inspiring intense waves of xenophobia. America was primed for violence—and to Galleani and his followers, destroying the state was the only conceivable path.

The spectacular violence of 1919 and 1920 proved a catalyst. A concerted nationwide hunt for anarchists began. This work, which culminated in what came to be known as the Palmer Raids, entailed direct violations of the Constitution. In late 1919 and early 1920, a series of raids—carried out in more than 30 American cities—led to the warrantless arrests of 10,000 suspected radicals, mostly Italian and Jewish immigrants. Attorney General Palmer’s dragnet ensnared many innocent people and has become a symbol of the damage that overzealous law enforcement can cause. Hundreds of people were ultimately deported. Some had fallen afoul of a harsh new federal immigration law that broadly targeted anarchists. One of them was Luigi Galleani. “The law was kind of designed for him,” Beverly Gage, a historian and the author of The Day Wall Street Exploded, told me.

The violence did not stop immediately after the Palmer Raids—in an irony that frustrated authorities, Galleani’s deportation made it impossible for them to charge him in the Wall Street bombing, which they believed he planned, because it occurred after he’d left the country. Nevertheless, sweeping action by law enforcement helped put an end to a generation of anarchist attacks.

That is the most important lesson from the anarchist period: Holding perpetrators accountable is crucial. The Palmer Raids are remembered, rightly, as a ham-handed application of police-state tactics. Government actions can turn killers into martyrs. More important, aggressive policing and surveillance can undermine the very democracy they are meant to protect; state violence against citizens only validates a distrust of law enforcement.

But deterrence conducted within the law can work. Unlike anti-war protesters or labor organizers, violent extremists don’t have an agenda that invites negotiation. “Today’s threats of violence can be inspired by a wide range of ideologies that themselves morph and shift over time,” Deputy Homeland Security Adviser Josh Geltzer told me. Now as in the early 20th century, countering extremism through ordinary debate or persuasion, or through concession, is a fool’s errand. Extremists may not even know what they believe, or hope for. “One of the things I increasingly keep wondering about is—what is the endgame?” Mary McCord, a former assistant U.S. attorney and national-security official, told me. “Do you want democratic government? Do you want authoritarianism? Nobody talks about that. Take back our country . Okay, so you get it back. Then what do you do?”

III. CREEPING VIOLENCE

In another country, and in a time closer to our own, a sustained outbreak of domestic terrorism brought decades of attacks—and illustrates the role that ordinary citizens can sometimes play, along with deterrence, in restoring stability.

On Saturday, August 2, 1980, a bomb hidden inside a suitcase blew up at the Bologna Centrale railway station, killing 85 people and wounding hundreds more, many of them young families setting off on vacation. The explosion flattened an entire wing of the station, demolishing a crowded restaurant, wrecking a train platform, and freezing the station’s clock at the time of the detonation: 10:25 a.m.

The Bologna massacre remains the deadliest attack in Italy since World War II. By the time it occurred, Italians were more than a decade into a period of intense political violence, one that came to be known as Anni di Piombo, or the “Years of Lead.” From roughly 1969 to 1988, Italians experienced open warfare in the streets, bombings of trains, deadly shootings and arson attacks, at least 60 high-profile assassinations, and a narrowly averted neofascist coup attempt. It was a generation of death and bedlam. Although exact numbers are difficult to come by, during the Years of Lead, at least 400 people were killed and some 2,000 wounded in more than 14,000 separate attacks.

As I sat at the Bologna Centrale railway station in September, a place where so many people had died, I found myself thinking, somewhat counterintuitively, about how, in the great sweep of history, the political violence in Italy in the 1970s and ’80s now seems but a blip. Things were so terrible for so long. And then they weren’t. How does political violence come to an end?

No one can say precisely what alchemy of experience, temperament, and circumstance leads a person to choose political violence. But being part of a group alters a person’s moral calculations and sense of identity, not always for the good. Martin Luther King Jr., citing the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, wrote in his “Letter From Birmingham Jail” that “groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.” People commit acts together that they’d never contemplate alone.

Vicky Franzinetti was a teenage member of the far-left militant group Lotta Continua during the Years of Lead. “There was a lot of what I would call John Wayneism, and a lot of people fell for that,” she told me. “Whether it’s the Black Panthers or the people who attacked on January 6 on Capitol Hill, violence has a mesmerizing appeal on a lot of people.” A subtle but important shift also took place in Italian political culture during the ’60s and ’70s as people grasped for group identity. “If you move from what you want to who you are, there is very little scope for real dialogue, and for the possibility of exchanging ideas, which is the basis of politics,” Franzinetti said. “The result is the death of politics, which is what has happened.”

In talking with Italians who lived through the Years of Lead about what brought this period to an end, two common themes emerged. The first has to do with economics. For a while, violence was seen as permissible because for too many people, it felt like the only option left in a world that had turned against them. When the Years of Lead began, Italy was still fumbling for a postwar identity. Some Fascists remained in positions of power, and authoritarian regimes controlled several of the country’s neighbors—Greece, Portugal, Spain, Turkey. Not unlike the labor movements that arose in Galleani’s day, the Years of Lead were preceded by intensifying unrest among factory workers and students, who wanted better social and working conditions. The unrest eventually tipped into violence, which spiraled out of control. Leftists fought for the proletariat, and neofascists fought to wind back the clock to the days of Mussolini. When, after two decades, the economy improved in Italy, terrorism receded.

The second theme was that the public finally got fed up. People didn’t want to live in terror. They said, in effect: Enough. Lotta Continua hadn’t resorted to violence in the early years. When it did grow violent, it alienated its own members. “I didn’t like it, and I fought it,” Franzinetti told me. Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi, a sociology professor at UC Santa Barbara who lived in Rome at the time, recalled: “It went too far. Really, it reached a point that was quite dramatic. It was hard to live through those times.” But it took a surprisingly long while to reach that point. The violence crept in—one episode, then another, then another—and people absorbed and compartmentalized the individual events, as many Americans do now. They did not understand just how dangerous things were getting until violence was endemic. “It started out with the kneecappings,” Joseph LaPalombara, a Yale political scientist who lived in Rome during the Years of Lead, told me, “and then got worse. And as it got worse, the streets emptied after dark.”

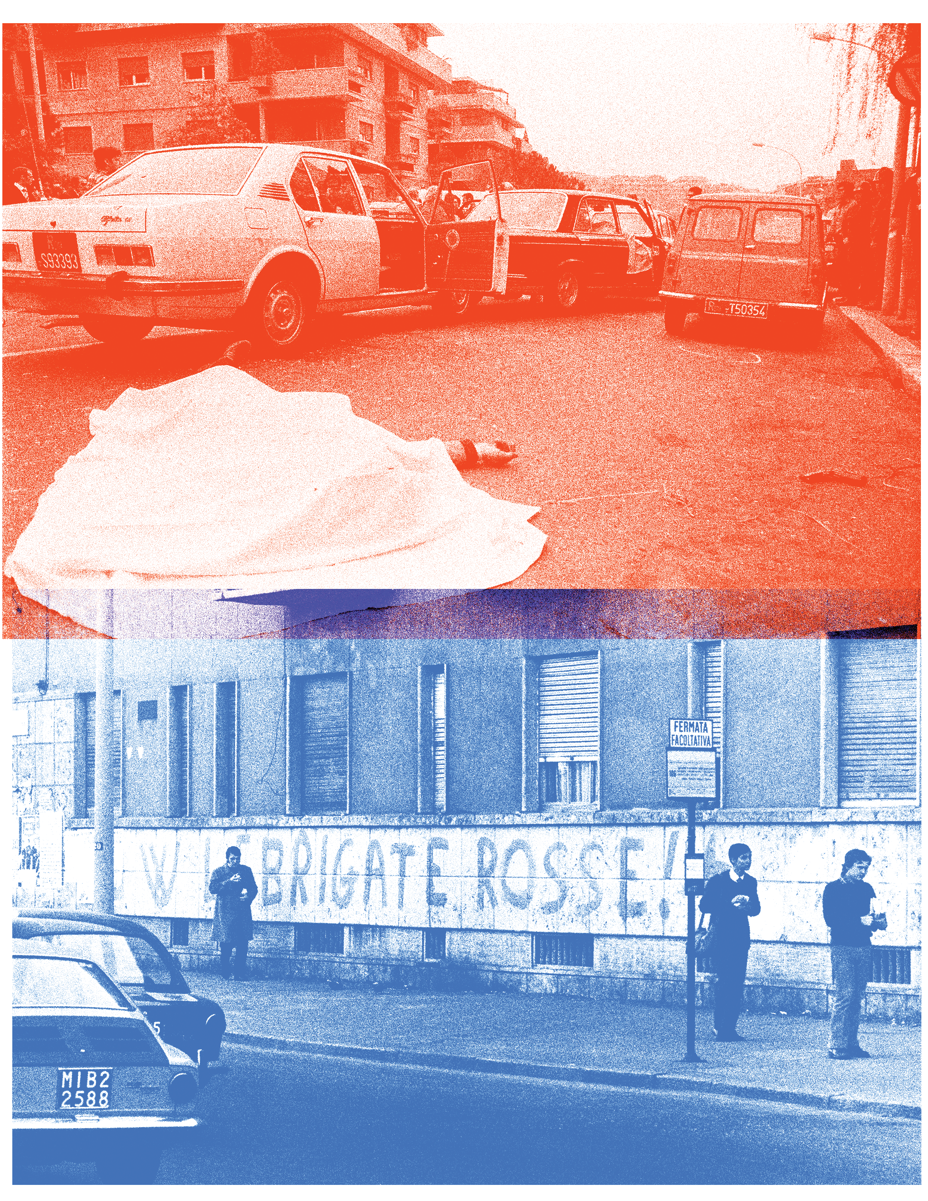

A turning point in public sentiment, or at least the start of a turning point, came in the spring of 1978, when the leftist group known as the Red Brigades kidnapped the former prime minister and leader of the Christian Democrats Aldo Moro, killing all five members of his police escort and turning him into an example of how We don’t negotiate with terrorists can go terrifically wrong. Moro was held captive and tortured for 54 days, then executed, his body left in the back of a bright-red Renault on a busy Rome street. In a series of letters his captors allowed him to send, Moro had begged Italian officials to arrange for his freedom with a prisoner exchange. They refused. After his murder, the final letter he’d written to his wife, “my dearest Noretta,” roughly 10 days before his death, was published in a local newspaper. “In my last hour I am left with a profound bitterness at heart,” he wrote. “But it is not of this I want to talk but of you whom I love and will always love.” Moro did not want a state funeral, but Italy held one anyway.

The conventional wisdom among terrorism experts had been that terrorists wanted publicity but didn’t really want to kill people—or, as the Rand Corporation’s Brian Jenkins put it in 1975, “Terrorists want a lot of people watching, not a lot of people dead.” But conditions had become so bad by the time Moro was murdered that newspapers around the world were confused when days passed without a political killing or shooting in Italy. “Italians Puzzled by 10-Day Lull in Terrorist Activity,” read one headline in The New York Times a few weeks after Moro’s murder. “When he was killed, it got a lot more serious,” Alexander Reid Ross, who hosts a history podcast about the era called Years of Lead Pod, told me. “People stopped laughing. It was no longer something where you could say, ‘It’s a sideshow.’ ”

The Moro assassination was followed by an intensification of violence, including the Bologna-station bombing. People who had ignored the violence now paid attention; people who might have been tempted by revolution now stayed home. Meanwhile, the crackdown that followed—which involved curfews, traffic stops, a militarized police presence, and deals with terrorists who agreed to rat out their collaborators—caused violent groups to implode.

The example of Aldo Moro offers a warning. It shouldn’t take an act like the assassination of a former prime minister to shake people into awareness. But it often does. William Bernstein, the author of The Delusions of Crowds, is not optimistic that anything else will work: “The answer is—and it’s not going to be a pleasant answer—the answer is that the violence ends if it boils over into a containable cataclysm.” What if, he went on—“I almost hesitate to say this”—but what if they actually had hanged Mike Pence or Nancy Pelosi on January 6? “I think that would have ended it. I don’t think it ends without some sort of cathartic cataclysm. I think, absent that, it just boils along for a generation or two generations.” Bernstein wasn’t the only expert to suggest such a thing.

No wonder some American politicians are terrified. “We’ve had an exponential increase in threats against members of Congress,” Senator Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat from Minnesota, told me in January. Klobuchar thought back to when she was standing at President Joe Biden’s inauguration ceremony, two weeks after the attempted insurrection. At the time, as Democrats and most Republicans came together for a peaceful transfer of power, she felt as though a violent eruption in American history might be ending. But Klobuchar now believes she was “naive” to think that Republicans would break with Trump and restore the party’s democratic values. “We have Donald Trump, his shadow, looming over everything,” she said.

This past February, Biden sought to dispel that shadow as he stood before Congress to deliver his State of the Union address. “There’s no place for political violence in America,” he said. “And we must give hate and extremism in any form no safe harbor.” Biden’s speech was punctuated by jeers and name-calling by Republicans.

IV. A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT

The taxonomy of what counts as political violence can be complicated. One way to picture it is as an iceberg: The part that protrudes from the water represents the horrific attacks on both hard targets and soft ones, in which the attacker has explicitly indicated hatred for the targeted group—fatal attacks at supermarkets and synagogues, as well as assassination attempts such as the shooting at a congressional-Republican baseball practice in 2017. Less visible is the far more extensive mindset that underlies them. “There are a lot of people who are out for a protest, who are advocating for violence,” Erin Miller, the longtime program manager at the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database, told me. “Then there’s a smaller number at the tip of the iceberg that are willing to carry out violent attacks.” You can’t get a grip on political violence just by counting the number of violent episodes. You have to look at the whole culture.

A society’s propensity for political violence—including cataclysmic violence—may be increasing even as ordinary life, for many people, probably most, continues to feel normal. A drumbeat of violent attacks, by different groups with different agendas, may register as different things. But collectively, as in Italy, they have the power to loosen society’s screws.

In December, I spoke again with Alexander Reid Ross, who in addition to hosting Years of Lead Pod is a lecturer at Portland State University. We met in Pioneer Courthouse Square, in downtown Portland. I had found the city in a wounded condition. This was tragic to me two times over—first, because I knew what had happened there, and second, because I had immediately absorbed Portland’s charm. You can’t encounter all those drawbridges, or the swooping crows, or the great Borgesian bookstore, or the giant elm trees and do anything but fall in love with the place. But downtown Portland was not at its best. The first day I was there I counted more birds than people, and many of the people I saw were quite obviously struggling badly.

On the gray afternoon when we met, Ross and I happened to be sitting at the site of the first far-right protest he remembers witnessing in his city, back in 2016; members of a group called Students for Trump, stoked by Alex Jones’s disinformation outlet, Infowars, had gathered to assert their political preferences and provoke their neighbors. Ross is a geographer, a specialty he assumed would keep him focused on land-use debates and ecology, which is one of the reasons he moved to Oregon in the first place. After that 2016 rally, Ross paid closer attention to the political violence unfolding in Portland. We decided to take a walk so that Ross could point out various landmarks from the—well, we couldn’t decide what to call the period of sustained violence that started in 2016 and was reignited in 2020. The siege? The occupation? The revolt? What happened in Portland has a way of being too slippery for precise language.

We walked southwest from the square before doubling back toward the Willamette River. Over here was the historical society that protesters broke into and vandalized one night. Over there was where the statues got toppled. (“Portland is a city of pedestals now,” Ross said.) A federal building still had a protective fence surrounding it more than a year after the street violence had ended. At one point, the mayor had to order a drawbridge raised to keep combatants apart.

On the evening of June 30, 2018, Ross found himself in the middle of a violent brawl between hundreds of self-described antifa activists and members of the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer, a local pro-Trump offshoot. Ross described to me a number of “ghoulish” encounters he’d had with Patriot Prayer, and I asked him which moment was the scariest. “It’s on video,” he told me. “You can see it: me getting punched.” I later watched the video. In it, Ross rushes toward a group of men who are repeatedly kicking and bludgeoning a person dressed all in black, lying in the street. Ross had told me earlier that he’d intervened because he thought he was watching someone being beaten to death. After Ross gets clocked, he appears dazed, then dashes back toward the fight. “That’s enough! That’s enough!” he shouts.

By the time of this fight, Patriot Prayer had become a fixture in Portland. Its founder, Joey Gibson, has said in interviews that he was inspired to start Patriot Prayer to fight for free speech, but the group’s core belief has always been in Donald Trump. Its first event, in Vancouver, Washington, in October 2016, was a pro-Trump rally. From there, Gibson deliberately picked ultraliberal cities such as Portland, Berkeley, Seattle, and San Francisco for his protests, and in doing so quickly attracted like-minded radicals—the Proud Boys, the Three Percenters, Identity Evropa, the Hell Shaking Street Preachers—who marched alongside Patriot Prayer. These were people who seemed to love Trump and shit-stirring in equal measure. White nationalists and self-described Western chauvinists showed up at Gibson’s events. (Gibson’s mother is Japanese, and he has insisted that he does not share their views.) By August 2018, Patriot Prayer had already held at least nine rallies in Portland, routinely drawing hundreds of supporters—grown men in Boba Fett helmets and other homemade costumes; at least one man with an SS neck tattoo. In 2019, Gibson himself was arrested on a riot charge. Patriot Prayer quickly became the darling of Infowars.

The morning after I met Ross, I drove across the river to Vancouver, a town of strip-mall churches and ponderosa pine trees, to meet with Lars Larson, who records The Lars Larson Show—tagline: “Honestly Provocative Talk Radio”—from his home studio. Larson greeted me with his two dogs and a big mug of coffee. His warmth, quick-mindedness, and tendency to filibuster make him irresistible for talk radio. And his allegiance to MAGA world helps him book guests like Donald Trump Jr., whom Larson introduced on a recent episode as “the son of the real president of the United States of America.” Over the course of our conversation, he described January 6 as “some ruined furniture in the Capitol”; suggested that the city government of Charlottesville, Virginia, was secretly behind the violent clash at the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally; and made multiple references to George Soros, including suggesting that Soros may have paid for people to come to Portland to tear up the city. When I pressed Larson on various points, he would walk back whatever he had claimed, but only slightly. He does not seem to be a conspiracy theorist, but he plays one on the radio.

Larson blamed Portland’s troubles on a culture of lawlessness fostered by a district attorney who, he said, repeatedly declined to prosecute left-wing protesters. He sees this as an uneven application of justice that undermined people’s faith in local government. It is more accurate to say that the district attorney chose not to prosecute lesser crimes, focusing instead on serious crimes against people and property; ironically, the complaint about uneven application comes from both the far left and the far right. When I asked Larson whether Patriot Prayer is Christian nationalist in ideology, the question seemed to make him uncomfortable, and he emphasized his belief in pluralism and religious freedom. He also compared Joey Gibson and Patriot Prayer marching on Portland to civil-rights activists marching on Selma in 1965. “What I heard people tell Patriot Prayer is ‘If you get attacked every time you go to Portland, don’t go to Portland,’ ” he told me. “Would you have given that same advice to Martin Luther King?”

Gibson’s lawyer Angus Lee accused the government of “political persecution”; Gibson was ultimately acquitted of the riot charge. Patriot Prayer, Lee went on, is “not like these other organizations you referenced that have members and that sort of thing. Patriot Prayer is more of an idea.” Gibson himself once put it in blunter terms. “I don’t even know what Patriot Prayer is anymore,” he said in a 2017 interview on a public-access news channel in Portland. “It’s just these two words that people hear and it sparks emotions … All Patriot Prayer is is videos and social-media presence.”

The more I talked with people about Patriot Prayer, the more it began to resemble a phenomenon like QAnon—a decentralized and amorphous movement designed to provoke reaction, tolerant of contradictions, borrowing heavily from internet culture, overlapping with other extremist movements like the Proud Boys, linked to high-profile episodes of violence, and ultimately focused on Trump. I couldn’t help but think of Galleani, his “beautiful idea,” and the diffuse ideology of his followers. One key difference: Galleani was fighting against the state, whereas movements like QAnon and groups like Patriot Prayer and the Proud Boys have been cheered on by a sitting president and his party.

When I met with Portland’s mayor, Ted Wheeler, at city hall, he recalled night after night of violence, and at times planning for the very worst, meaning mass casualties. Portlanders had taken to calling him “Tear Gas Ted” because of the police response in the city. One part of any mayor’s job is to absorb the community’s scorn. Few people have patience for unfilled potholes or the complexities of trash collection. Disdain for Wheeler may have been the one thing that just about every person I met in Portland shared, but his job has been difficult even by big-city standards. He confronted a breakdown of the social contract.

“Political violence, in my opinion, is the extreme manifestation of other trends that are prevalent in our society,” Wheeler told me. “A healthy democracy is one where you can sit on one side of the table and express an opinion, and I can sit on the other side of the table and express a very different opinion, and then we have the contest of ideas … We have it out verbally. Then we go drink a beer or whatever.”

When extremists began taunting Portlanders online, it was very quickly “game on” for violence in the streets, Wheeler said. In this way, Portland stands as a warning to cities that now seem calm: It takes very little provocation to inflame latent tensions between warring factions. Once order collapses, it is extraordinarily difficult to restore. And it can be dangerous to attempt to do so through the use of force, especially when one violent faction is lashing out, in part, against state authority.

Aaron Mesh moved to Portland 16 years ago, to take a job as Willamette Week’s film critic, and since then has worked his way up to managing editor. He is sharp-tongued and good-humored, and it is obvious that he loves his city in the way that any good newspaperman does, with a mix of fierce loyalty and heaping criticism. Like Wheeler, he trained attention on the dynamic of action and reaction—on how rising to the bait not only solves nothing but can make things worse. “There was this attitude of We’re going to theatrically subdue your city with these weekend excursions,” Mesh said, describing the confrontations that began in 2016 as a form of cosplay, with right-wing extremists wearing everything from feathered hats to Pepe the Frog costumes and left-wing extremists dressed up in what’s known as black bloc: all-black clothing and facial coverings. “I do want to emphasize,” he said, “that everyone involved in this was a massive fucking loser, on both sides.”

It was as though all of the most unsavory characters on the internet had crawled out of the computer. The fights were enough of a spectacle that not everyone took them seriously at first. Mesh said it was impossible to overstate “the degree to which Portland became a lodestone in the imagination of a nascent Proud Boys movement,” a place where paramilitary figures on the right went “to prove that they had testicles.” He went on: “You walk into town wearing a helmet and carrying a big American flag” and then wait and see “who throws an egg at your car or who gives you the middle finger, and you beat the living hell out of them.”

Both sides behaved despicably. But only the right-wingers had the endorsement of the president and the mainstream Republican Party. “Despite being run by utter morons,” Mesh said of Patriot Prayer, “they managed to outsmart most of their adversaries in this city, simply by provoking violent reactions from people who were appalled by their politics.” The argument for violence among people on the left is often, essentially, If you encounter a Nazi, you should punch him. But “what if the only thing the Nazi wants is for you to punch him?” Mesh asked. “What if the Nazis all have cameras and they’re immediately feeding all the videos of you punching them to Tucker Carlson? Which is what they did.”

The situation in Portland became so desperate, and the ideologies involved so tangled, that the violence began to operate like its own weather system—a phenomenon that the majority of Portlanders could see coming and avoid, but one that left behind tremendous destruction. Most people don’t want to fight. But it takes startlingly few violent individuals to exact generational damage.

V. THE COMPLICIT STATE

America was born in revolution, and violence has been an undercurrent in the nation’s politics ever since. People remember the brutal opposition to the civil-rights struggle, and recall the wave of terrorism spawned by the anti-war movement of the 1960s. But the most direct precursor to what we’re experiencing now is the anti-government Patriot movement, which can be traced to the 1980s and eventually led to deadly standoffs between federal agents and armed citizens at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, in 1992, and in Waco, Texas, in 1993. Three people were killed at Ruby Ridge. As many as 80 died in Waco, 25 of them children. Those incidents stirred the present-day militia movement and directly inspired the Oklahoma City bombers, anti-government extremists who killed 168 people at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in 1995. The surge in militia activity, white nationalism, and apocalypticism of the 1990s seemed to peter out in the early 2000s. This once struck me as a bright spot, an earlier success we might learn from today. But when I mentioned this notion to Carolyn Gallaher, a scholar who spent two years following a right-wing paramilitary group in Kentucky in the 1990s, she said, “The militia movement waned very quickly in the 1990s not because of anything we did, but because of Oklahoma City. That bombing really put the movement on the back foot. Some groups went underground. Some groups dispersed. You also saw that happen with white-supremacist groups.”

A generation later, political violence in America unfolds with little organized guidance and is fed by a mishmash of extremist right-wing views. It predates the emergence of Donald Trump, but Trump served as an accelerant. He also made tolerance of political violence a defining trait of his party, whereas in the past, both political parties condemned it. At the height of the Patriot movement, “there was this fire wall” between extremist groups and elected officials that protected democratic norms, according to Gallaher. Today, “the fire wall between these guys and formal politics has melted away.” Gallaher does not anticipate an outbreak of civil strife in America in a “classic sense”—with Blue and Red armies or militias fighting for territory. “Our extremist groups are nowhere near as organized as they are in other countries.”

Because it is chaotic, Americans tend to underestimate political violence, as Italians at first did during the Years of Lead. Some see it as merely sporadic, and shift attention to other things. Some say, in effect, Wake me when there’s civil war. Some take heart from moments of supposed reprieve, such as the poor showing by election deniers and other extremists in the 2022 midterm elections. But think of all the ongoing violence that at first glance isn’t labeled as being about politics per se, but is in fact political: the violence, including mass shootings, directed at LGBTQ communities, at Jews, and at immigrants, among others. In November, the Department of Homeland Security issued a bulletin warning that “the United States remains in a heightened threat environment” due to individuals and small groups with a range of “violent extremist ideologies.” It warned of potential attacks against a long list of places and people: “public gatherings, faith-based institutions, the LGBTQI+ community, schools, racial and religious minorities, government facilities and personnel, U.S. critical infrastructure, the media, and perceived ideological opponents.”

The broad scope of the warning should not be surprising—not after the massacres in Pittsburgh, El Paso, Buffalo, and elsewhere. One month into 2023, the pace of mass shootings in America—all either political or, inevitably, politicized—was at an all-time high. “There’s no place that’s immune right now,” Mary McCord, the former assistant U.S. attorney, observed. “It’s really everywhere.” She added, “Someday, God help us, we’ll come out of this. But it’s hard for me to imagine how.”

The sociologist Norbert Elias, who left Germany for France and then Britain as the Nazi regime took hold, famously described what he called the civilizing process as “a long sequence of spurts and counter-spurts,” warning that you cannot fix a violent society simply by eliminating the factors that made it deteriorate in the first place. Violence and the forces that underlie it have the potential to take us from the democratic backsliding we already know to a condition known as decivilization. In periods of decivilization, ordinary people fail to find common ground with one another and lose faith in institutions and elected leaders. Shared knowledge erodes, and bonds fray across society. Some people inevitably decide to act with violence. As violence increases, so does distrust in institutions and leaders, and around and around it goes. The process is not inevitable—it can be held in check—but if a period of bloodshed is sustained for long enough, there is no shortcut back to normal. And signs of decivilization are visible now.

“The path out of bloodshed is measured not in years but in generations,” Rachel Kleinfeld writes in A Savage Order, her 2018 study of extreme violence and the ways it corrodes a society. “Once a democracy descends into extreme violence, it is always more vulnerable to backsliding.” Cultural patterns, once set, are durable—the relatively high rates of violence in the American South, in part a legacy of racism and slaveholding, persist to this day. In The Delusions of Crowds, William Bernstein looks further afield, to Germany. He told me, “You can actually predict anti-Semitism and voting for the Nazi Party by going back to the anti-Semitism across those same regions in the 14th century. You can trace it city to city.”

Three realities mark the current era of political violence in America as different from what has come before, and make dealing with it much harder. The first—obvious—is the universal access to weaponry, including military-grade weapons.

Second, today’s information environment is simultaneously more sophisticated and more fragmented than ever before. In 2006, the analyst Bruce Hoffman argued that contemporary terrorism had become dangerously amorphous. He was referring to groups like al-Qaeda, but we now witness what he described among domestic American extremists. As Hoffman and others see it, the defining characteristic of post-9/11 terrorism is that it is decentralized. You don’t need to be part of an organization to become a terrorist. Hateful ideas and conspiracy theories are not only easy to find online; they’re actively amplified by social platforms, whose algorithms prioritize the anger and hate that drive engagement and profit. The barriers to radicalization are now almost nonexistent. Luigi Galleani would have loved Twitter, YouTube, and Telegram. He had to settle for publishing a weekly newspaper. Because of social media, conspiracy theories now spread instantly and globally, often promoted by hugely influential figures in the media, such as Tucker Carlson and of course Trump, whom Twitter and Facebook have just reinstated.

The third new reality goes to the core of American self-governance: people refusing to accept the outcome of elections, with national leaders fueling the skepticism and leveraging it for their own ends. In periods of decivilization, violence often becomes part of a governing strategy. This can happen when weak states acquiesce to violence simply to survive. Or it can happen when politicians align themselves with violent groups in order to bolster authority—a characteristic of what Kleinfeld, in her 2018 book, calls a “complicit state.” This is a well-known tactic among authoritarian incumbents worldwide who wield power by mobilizing state and vigilante violence in tandem.

Complicity is insidious. It doesn’t require a revolution. You can see complicity, for example, in Trump’s order to the Proud Boys to “stand back and stand by” in the months ahead of January 6. You can see it in the Republican Party’s defense of Trump even after he propelled insurrectionists toward the U.S. Capitol. And you can see it in the way that powerful politicians and television personalities continue to cheer on right-wing extremists as “patriots” and “political prisoners,” rather than condemning them as vigilantes and seditionists.

Americans sometimes wonder what might have happened if the Civil War had gone the other way—what the nation would be like now, or whether it would even exist, if the South had won. But that thought experiment overlooks the fact that we do know what it looks like for violent extremists to win in the United States. In the 1870s, white supremacists who objected to Reconstruction led a campaign of violence that they perversely referred to as Redemption. They murdered thousands of Black people in terror lynchings. They drove thousands more Black business owners, journalists, and elected officials out of their homes and hometowns, destroying their livelihoods. Sometimes violence ends not because it is overcome, but because it has achieved its goal.

Norbert Elias’s warnings notwithstanding, dealing seriously with society’s underlying pathologies is part of the answer to political violence in the long term. But so, too, is something we have not had and perhaps can barely imagine anymore: leaders from all parts of the political constellation, and at all levels of government, and from all segments of society, who name the problem of political violence for what it is, explain how it will overwhelm us, and point a finger at those who foment it, either directly or indirectly. Leaders who understand that nothing else will matter if we can’t stop this one thing. The federal government is right to take a hard line against political violence—as it has done with its prosecutions of Governor Whitmer’s would-be kidnappers and the January 6 insurrectionists (almost 1,000 of whom have been charged). But violence must also be confronted where it first takes root, in the minds of citizens.

Ending political violence means facing down those who use the language of democracy to weaken democratic systems. It means rebuking the conspiracy theorist who uses the rhetoric of truth-seeking to obscure what’s real; the billionaire who describes his privately owned social platform as a democratic town square; the seditionist who proclaims himself a patriot; the authoritarian who claims to love freedom. Someday, historians will look back at this moment and tell one of two stories: The first is a story of how democracy and reason prevailed. The second is a story of how minds grew fevered and blood was spilled in the twilight of a great experiment that did not have to end the way it did.

*Lead image source credits from left to right: Kathryn Elsesser / AFP / Getty; Michael Nigro / Sipa USA / Alamy; Mathieu Lewis-Rolland / AFP / Getty; Alex Milan Tracy / AP; Michael Nigro / Sipa USA / Alamy; Michael Nigro / Sipa USA / AP; Mathieu Lewis-Rolland / AFP / Getty; Mark Downey / ZUMA / Alamy; Mathieu Lewis-Rolland / AFP / Getty

This article appears in the April 2023 print edition with the headline “The New Anarchy.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.