Critics have been raking Ridley Scott’s new movie about Napoléon Bonaparte over the coals for its many historical inaccuracies.

As a scholar of French colonialism and slavery who studies historical fiction, or the fictionalization of real events, I was much less bothered by most of the liberties taken in “Napoleon” – although shooting cannons at the pyramids did seem like one indulgence too far.

I have argued elsewhere that historical fictions need not necessarily be judged by adherence to facts. Instead, inventiveness, creativity, ideology and, ultimately, storytelling power are what matter most.

But in lieu of offering a fresh and imaginative take on Napoléon, Scott’s film rehearsed the well-known battles of Austerlitz, Wagram and Waterloo, while erasing perhaps the most momentous – and consequential – of Bonaparte’s military campaigns.

As with every other Napoléon movie, Scott’s version will leave viewers with no understanding of the genocidal war to restore slavery that Bonaparte waged against Black revolutionaries in the French colony of Saint-Domingue – what’s known as Haiti today.

To me, leaving out this history is akin to making a movie about Hitler without mentioning the Holocaust.

‘I am for the whites, because I am white’

France’s seemingly eternal on-again, off-again war with Great Britain did not change the immediate boundaries of either country. These wars were often fought over land in the American hemisphere and included a historic contest over Martinique, a small island in the Caribbean, whose fate had far-reaching repercussions for slavery.

In 1794, following three years of slave rebellions in Saint-Domingue – events now known as the Haitian Revolution – the French government abolished slavery in all French overseas territories.

Martinique, however, was not included: The French had recently lost the island to the British in battle.

In a 1799 speech to the French government, Bonaparte explained that if he had been in Martinique at the time the French lost the colony, he would have been on the side of the British – because they never dared to abolish slavery.

“I am for the whites, because I am white,” Bonaparte said. “I have no other reason, and this is the right one. How could anyone have granted freedom to Africans, to men who had no civilization.”

Once he rose to power, Bonaparte signed the 1802 Treaty of Amiens with the British, which returned Martinique to French rule. Afterward, he passed a law permitting slavery to continue in Martinique. And in July 1802, Bonaparte formally reinstated slavery on Guadeloupe, another French colony in the Caribbean. Slavery then persisted in France’s overseas empire until 1848, long after his death in 1821.

Meanwhile, in Saint-Domingue, Bonaparte authorized his generals to eliminate the majority of the adult Black population, and he signed a law to reinstate the slave trade to the island.

A Black general’s rise

For the mission to succeed, Bonaparte’s troops would have to contend with a formerly enslaved man called Toussaint Louverture, who had become a prominent leader during the early years of the Haitian Revolution.

After general emancipation, when the Black population had become citizens – rather than slaves – of France, Louverture joined the French army. He went on to play a key role in helping France combat and eventually defeat Spanish and British forces, who had since invaded the colony in an attempt to take it over.

Recognizing his military prowess, the French consistently promoted Louverture until he became the second Black general in a French army – after General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, father of the famous French novelist Alexandre Dumas. (Thomas-Alexandre Dumas incidentally appears in the film as a character with a nonspeaking part.)

In 1801, as a testament to his growing authority, Louverture issued a famous constitution that appointed him governor-general of the whole island. Yet he still professed fealty to France even as the colony became semi-autonomous.

By then, however, Bonaparte had assumed power as first consul of France – and had made it his mission to “annihilate the government of the Blacks” in Saint-Domingue so he could bring back slavery.

In January 1802, Bonaparte sent his brother-in-law Charles Victor Emmanuel Leclerc to Saint-Domingue with tens of thousands of French troops.

Arrest Louverture and reinstate slavery.

The fall of Louverture

One of the film’s writers, David Scarpa, said Napoléon represents for him “the classic example of the benevolent dictator.”

If that Napoléon ever did exist, Louverture never met him.

In June 1802, Napoléon’s army arrested Louverture and deported him to France. As Louverture wasted away in a French prison, Bonaparte refused to put Louverture on trial. Throughout his incarceration, the guards at the jail denied Louverture food, water, heat and medical care. Louverture subsequently starved and froze to death.

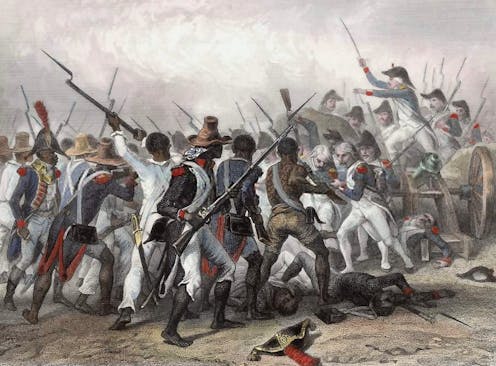

With Louverture gone, Napoléon’s army operated with more bloodlust than ever before. In addition to conventional weapons, his troops fought the freedom fighters with floating gas chambers, mass drownings and dog attacks – all in the name of restoring slavery.

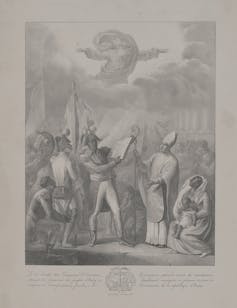

The Black freedom fighters, now calling themselves the armée indigène, led by Haiti’s founder General Jean-Jacques Dessalines, definitively defeated French forces in the historic Battle of Vertières on Nov. 18, 1803. On Jan. 1, 1804, they officially declared independence from France and changed the name of the island to Haiti.

‘A fatal move’

If the filmmakers had included Napoléon’s failed mission to restore slavery in Saint-Domingue, it could have served as a propitious moment to tie the movie back to one of its only coherent arcs: Napoléon’s undying love for Joséphine de Beauharnais, his first wife.

In one memorable scene in the film, Joséphine tells Bonaparte that he is nothing without her, and he agrees.

However, Joséphine’s posthumously published memoir suggests that Bonaparte disregarded his wife’s most prescient counsel. Joséphine wrote that she urged her husband not to send an expedition to Saint-Domingue, prophesying this as a “fatal move” that “would forever take this beautiful colony away from France.” She advised Bonaparte, alternatively, to “keep Toussaint Louverture there. That is the man required to govern the Blacks.”

She subsequently asked him, “What complaints could you have against this leader of the Blacks? He has always maintained correspondence with you; he has done even more, he has given you, in some sense, his children for hostages.”

Louverture’s children had attended Paris’ storied Collège de la Marche, alongside the children of other prominent Black Saint-Domingue officials. Although Bonaparte ended up sending Louverture’s children back to the colony with Leclerc, another Black general from Saint-Domingue who fought to oppose slavery’s reinstatement was not so lucky.

Just before Bonaparte’s troops began their genocidal war in the name of restoring slavery, Haiti’s future king, General Henry Christophe, sent his son, François Ferdinand, to the Collège de la Marche.

After the Haitian revolutionaries defeated France and declared the island independent in 1804, Bonaparte ordered the school closed. Many of its Black students, like young Ferdinand, were then thrown into orphanages. The abandoned child died alone in July 1805 at the age of 11.

Only at the end of his life, during his second exile on the remote island of St. Helena, did Napoléon express remorse for any of this.

“I can only reproach myself for the attempt on that colony,” the defunct emperor said. “I should have contented myself with governing it through Toussaint.”

A missed opportunity

By including some of this rich material, Ridley Scott could have made a truly original film with historical and contemporary relevance.

After all, Napoléon’s history of trying to stop the Haitian Revolution – the most significant revolution for freedom the modern world has ever seen – has never been depicted on a Hollywood screen.

Instead, hiding behind beautiful cinematography, magnificent costuming and Vanessa Kirby’s masterful portrayal of Joséphine, Scott ultimately produced an unimaginative film about the already well-trodden military successes and failures of the man depicted as having literally crowned himself France’s emperor.

If “Napoleon” doesn’t exactly glorify its main subject, its creators certainly seemed to sympathize with the man whose wars were responsible for more than 3,000,000 deaths, as the film’s final caption reads.

The film did not say whether that number includes the tens of thousands of Black people Napoléon’s army killed in Saint-Domingue.

Marlene Daut does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.