ARTS & CULTURE / JUNE 2024

The “Multi-Multi-Multi-Million-Dollar” Art Fraud That Shook the World

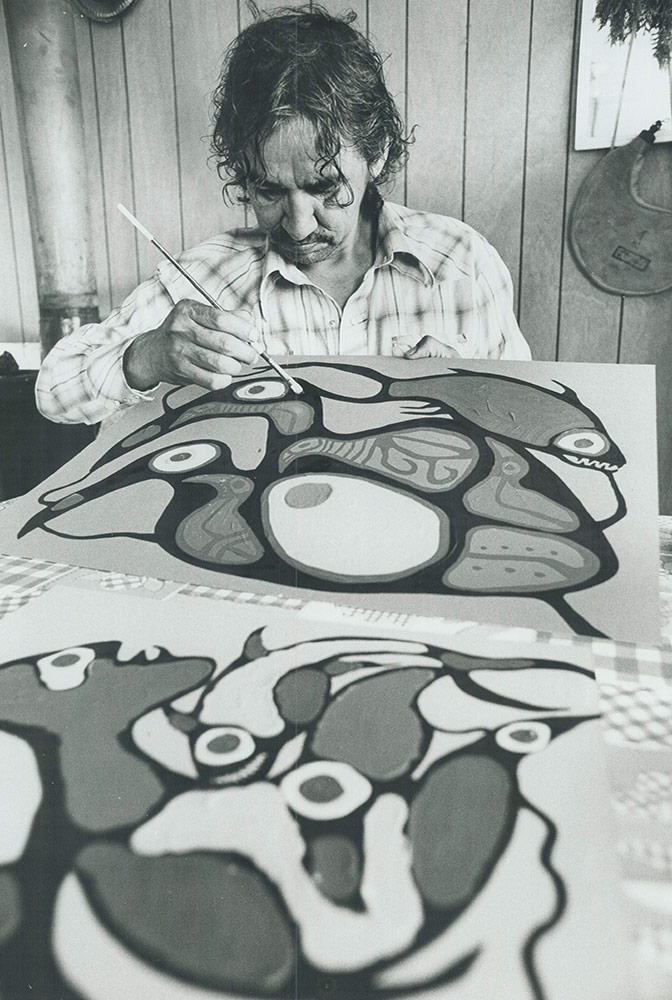

Norval Morrisseau was one of the most famous Indigenous artists anywhere. Then the fakes of his works surfaced—and kept coming

BY LUC RINALDI

Published 6:30, April 5, 2024

In the spring of 2005, Norval Morrisseau called a meeting to talk about “the fakes.” Picasso, Dalí, Van Gogh—many great artists have dealt with forgeries. Morrisseau, appointed to the Order of Canada and member of the Indigenous Group of Seven, was no exception. His paintings sold for tens of thousands of dollars, but so did fakes created by former apprentices, strangers, even his own relatives. For years, Morrisseau and Gabe Vadas, his business manager and adopted son, had witnessed dubious paintings pop up in galleries and collections across Canada. In one biography of Morrisseau, A Picasso in the North Country, the Thunder Bay author James R. Stevens wrote about a Manitoulin Island art dealer who brought Morrisseau photos of fifty pieces supposedly painted by the artist. Morrisseau set several aside. “The small pile, I might have had something to do with,” he said. “The rest, I’ve never seen before.” Another time, his friend Bryant Ross told me, Morrisseau was more blunt: “I didn’t paint those fucking things.”

At first, Vadas tried to educate galleries about the fakes, but few gallerists stopped selling them. So, on the advice of their lawyer, Morrisseau and Vadas invited trusted experts—art historians and independent curators who’d studied and shown his art—to their lawyer’s office in Toronto and asked them to create a definitive catalogue of his oeuvre. They called this group of volunteers the Norval Morrisseau Heritage Society. Like the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board, which had formed a decade earlier to validate Warhol’s work, the society’s job was to separate Morrisseau’s masterpieces from his imitators’ knock-offs.

It was a monumental task. Morrisseau had created thousands of works of art: paintings, drawings, carvings, pieces of clothing, furniture. Galleries and collectors sought these works because they were unlike anything they’d seen before. They were characterized by bold black lines and vibrant colours, depicting the birds, bears, and beasts of Ojibwe legends passed down by Morrisseau’s grandfather—imagery that was, at the time, uncommon in contemporary art. Morrisseau made these legends his own, melding traditional motifs with the Catholic iconography imprinted on him in residential school as well as the psychedelic symbols of Eckankar, a form of New Age spirituality he adopted later in life. His works were at once stoic and sexual, depicting Jesus on one canvas and a phallus on the next. He worked with different materials (paint, crayon, and, by some reports, orange juice and blood) on a variety of surfaces (birch bark, fridge doors, pizza boxes). He inspired others—artists who paint in his style are known as the Woodland School—but none rivalled his fame. Though his works could fetch huge sums, he often gifted them to friends or traded them. For reasons both good (his talent) and bad (his public struggles with substance use), he was frequently in the press.

A year later, in the summer of 2006, Vadas learned that Heffel, a reputable Toronto auction house, was selling a number of Morrisseau paintings. He identified a handful of them as fakes, and Heffel removed them from the auction. When Heffel informed Joseph Otavnik, the owner of two of those paintings—as well as of dozens more on the walls of his home—that it wouldn’t be selling his pieces, Otavnik sued Vadas, claiming that he’d devalued the paintings and prevented him from selling them for as much as $12,000 each. By then, Morrisseau had been living with Parkinson’s disease. In the lawsuit, Otavnik referred to Morrisseau’s diagnosis and made the claim that his history of alcohol use might have contributed to a memory disorder; the artist, Otavnik asserted, therefore couldn’t be trusted to verify his own paintings. (The people who were closest to Morrisseau at the time say he remained mentally sharp.) Otavnik implored the courts to instead trust the judgment of Joseph McLeod, a gallerist who sold Otavnik the paintings and swore they were real. Moreover, earlier in his career, Morrisseau had allegedly allowed his assistants to pass off their work as his own so that they could make more money. In his claim, Otavnik wrote, “Norval doesn’t even care if people are copying his style of painting or even if they are selling fakes.”

Morrisseau clearly cared. He and Vadas flew to Toronto, where the suit had been filed, to rally support from like-minded gallerists and settle the debate once and for all. But by then, the artist was in his mid-seventies and frail and was using a wheelchair; he’d suffered a stroke ten years earlier and had also had double knee surgery. While in Toronto, he was taken to Toronto General Hospital, where, on December 4, 2007, he died. He never got a chance to tell a judge he hadn’t painted those pieces. Years later, the fight over the fakes still rages.

In 1937, when Morrisseau was around six years old, he was separated from his family, who lived in what is now Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek First Nation, and sent to St. Joseph’s Indian Industrial School, nearly 200 kilometres away, in Thunder Bay. The cruelty of those years at a Roman Catholic residential school was documented in two biographies, Stevens’s A Picasso in the North Country and Ojibwe author Armand Garnet Ruffo’s Norval Morrisseau: Man Changing into Thunderbird. Morrisseau was forbidden from speaking Ojibwe or hugging his own brother. Nuns hit him with leather straps, and priests raped him. Drawing became a respite.

The school left scars. He started drinking at thirteen. In his twenties, he married a woman named Harriet Kakegamic, and they had seven children, but he was, by some reported accounts, a neglectful husband and father. He wholly dedicated himself to his craft and mission. “Morrisseau talked about bridging people together,” Vadas told me. “He talked about how we can no longer say, ‘That person is Black, that person is white, that person is Indian’—how, instead, we should just call each other brothers and sisters and be together as a community of humans.”

According to the two biographers, with little money to buy paint or canvas, Morrisseau salvaged materials from the local dump; he extracted pigments from Christmas decorations and tubes of lipstick to create paint, which he layered onto birch bark and scraps of paper. He sold his art at the general store in Red Lake, a small community in northern Ontario, which is where, in the late 1950s, he caught the attention of a fly-in doctor named Joseph Weinstein and his wife, Esther. The Weinsteins were wealthy art collectors from Montreal who, despite travelling the globe, had never seen art like Morrisseau’s. They granted him access to their vast library of art books, bought him art supplies, and urged him to continue creating.

It wasn’t long before Morrisseau graduated from the shelves of small-town gift shops to the walls of Toronto’s art galleries. In 1962, a gallery owner named Jack Pollock toured the towns around Lake Nipigon, north of Thunder Bay, teaching art classes. Along the way, he met Morrisseau. At the time, Morrisseau—six feet two, lanky, and lean—had a reputation as an eccentric. Amused by the artist and, more importantly, awed by his art, Pollock invited Morrisseau to mount a show at his gallery in Toronto. The exhibition that September was a sensation. All thirty-five paintings sold. Time magazine, one of the many outlets to cover the exhibition, wrote, “Few exhibits in Canadian art history have touched off a greater immediate stir.”

The show was a breakthrough for Morrisseau and a watershed moment for Indigenous art. For decades, works by First Nations, Métis, Inuit, and Native American artists had been regarded largely as historical artifacts rather than as artworks worthy of display in contemporary galleries. “Our art was done basically as tourist art,” Tom Hill, the late Six Nations curator, said in A Separate Reality: Norval Morrisseau, a documentary by filmmaker Paul Carvalho. “It was insignificant until Morrisseau comes along.”

Canada’s relationship with its original inhabitants was also changing that year: Indigenous people could vote in a federal election for the first time that June, and the government and establishment art institutions were slowly beginning to take notice of Indigenous arts. To the minds of cosmopolitan gallery goers, Morrisseau was a symbol of this progress. Collectors and art critics spoke of Pollock “discovering” him in the bush. Purchasing one of his paintings came to be seen as buying a piece of history; to some, it was also a tangible way to support Indigenous culture. Morrisseau never intended to be an Indigenous poster child, but he took the role seriously. “I am an example of my people,” he said in A Separate Reality. “The responsibility for me today is to be a great artist.”

In the ensuing decades, Morrisseau’s career blossomed. He held more shows in Canada as well as in Los Angeles and Paris. Marc Chagall, the French modernist, dubbed him the “Picasso of the North.” The National Film Board of Canada produced a short documentary called The Paradox of Norval Morrisseau that depicted him as the “noble savage”: an Indigenous creator who’d broken into the white art world. It was a world in which Morrisseau never felt fully comfortable. According to Ruffo, after Morrisseau was appointed to the Order of Canada, in 1978, the artist said, “First the white man drives my people down to the pits of hell with an army of missionaries, and then they honour him, lift him up on their shoulders, with this medal. What has been lost is lost, and no matter who he was before, that person is gone.”

A spirit of subversion ran through Morrisseau’s work, setting the stage for future generations of Indigenous artists to be more provocative. When he was invited to paint a mural for the Canadian Pavilion at Expo 67, he proposed a piece depicting a bear cub and baby suckling at the teat of Mother Earth. (The organizers balked, which prompted Morrisseau to walk away, leaving his assistant to complete an amended design.) Several years later, he painted a cynical masterpiece called The Gift, which showed a missionary giving Indigenous people two catastrophic presents: Christianity and smallpox. But Morrisseau didn’t just prod; he also tried to heal divides. In 1983, he presented one of his greatest works, Androgyny—a breathtaking yellow, blue, and maroon polyptych illustrating the interconnectedness of all things—as a gift to the people of Canada. It now hangs in Rideau Hall, the official residence of the governor general.

Morrisseau made plenty of money, but he never hung on to it very long. According to Stevens, after his first show at Pollock’s gallery, he used the money from sales to hire a taxi to take him home, a fourteen-hour drive from Toronto. He later spent earnings to buy parkas for homeless Indigenous men, to rent hotel rooms and party with his friends. Despite making millions, he spent much of his life in poverty. “The white man is always after material gain,” he is quoted as saying in A Picasso in the North Country. “To me, money is of no importance. I don’t want it.”

Morrisseau had many agents and assistants who would help with the management of day-to-day tasks. Some looked after him—saving money, sending cash to his wife and children, buying him supplies. Others took advantage. A number of his agents and gallerists kept more than their fair share of his proceeds. Some bought works from him when he was drunk, paying well below market value. And some of his apprentices—an ever-revolving cast of disciples, friends, and relatives who trained under him—began imitating his work, passing off pieces he’d never touched as authentic Morrisseaus and pocketing the money. Bryant Ross, who helped the artist manage his business affairs in the late 1980s and early ’90s, says that Morrisseau looked the other way at first. “Norval was a generous guy,” he says. “I think he knew back then but didn’t really try to interfere with it. He wanted his friends to do well, to be able to pay their rent and buy their groceries and live a good life.”

By the early 2000s, however, Morrisseau’s tolerance for these fakes was put to the test. While living in Thunder Bay in the 1990s, he befriended a man in his thirties, named Gary Lamont. Lamont was a local drug dealer and tough guy: when his customers failed to pay up, he was known to beat them with a baseball bat. In exchange for some paintings, Lamont let Morrisseau work out of a cabin he owned. Lamont was stunned by how much money Morrisseau’s pieces could fetch. When Morrisseau eventually stopped using the cabin, Lamont seemed to hatch a plan: What if he created and sold fake artwork to keep the cash flowing? He enlisted local Indigenous artists—including Morrisseau’s brother Wolf and nephew Benji—to start painting knock-offs in that same rustic cabin. They copied existing works or invented entirely new images in Morrisseau’s style. They signed each one with the same Cree syllabics that Morrisseau put in one of the bottom corners of every piece. (The syllabics translate to “Copper Thunderbird,” a name that was given to him by a member of the Midewiwin Society after he recovered from a life-threatening illness in his teens.) Lamont paid the artists in cash, alcohol, and drugs, and he used their Indian status cards to purchase art supplies tax free. His wife, Linda Tkachyk, allegedly managed a website to sell the paintings. According to the documentary There Are No Fakes, artists who worked in Lamont’s operation occasionally threw thirty or so pieces in a pickup truck and drove across the country, to Alberta or British Columbia, where they sold them for thousands of dollars apiece. As a cover for their unexplained income, Lamont and Tkachyk billeted young Indigenous men in their home. These teens and twenty-somethings had left their reserves for Thunder Bay in hopes of gaining a better education; instead, his victims later told the courts, Lamont raped many of them on a nightly basis.

Morrisseau never intended to be an Indigenous poster child, but he took the role seriously. “I am an example of my people. The responsibility for me today is to be a great artist.”

In 2012, a number of Lamont’s victims came forward to police. He was arrested and convicted on multiple charges—including sexual assault—but not art fraud. By then, much damage had already been done to Morrisseau’s oeuvre. Unbeknownst to art buyers and gallerists, Lamont’s assembly line had pumped hundreds of fake Morrisseaus into the market, enriching white art dealers often off the backs of impoverished Indigenous artists. As one of Lamont’s victims put it in There Are No Fakes, “Gary pretty much raped my culture.”

In 2010, the Art Gallery of Ontario invited the musician Kevin Hearn to guest-curate a show of works from his private art collection. Hearn, the keyboard player of Barenaked Ladies, owned a few Morrisseaus. Hearn especially admired his use of colour, which reminded him of the stained glass at a cathedral where he’d sung as a boy. He decided to include one of Morrisseau’s works, titled Spirit Energy of Mother Earth, a green-on-green canvas filled with sinister-looking creatures, in the AGO exhibition.

A few days after the exhibition opened, that June, Hearn got a call from Gerald McMaster, then the AGO’s curator of Canadian art. They’d taken Spirit Energy off the wall. McMaster explained that the painting, which Hearn believed Morrisseau had painted in the ’70s, may not be genuine. Embarrassed, he contacted Joseph McLeod, the gallerist who’d sold him the work in 2005. At first, he assumed it was a big misunderstanding. “I thought that we would compare our information and see what the truth was,” says Hearn. McLeod refused to entertain the idea that the painting was fake, and he wouldn’t give Hearn his money back. According to Hearn, McLeod told him “that would set off a chain of events that would result in the closing of my gallery.”

Undeterred, Hearn started working with Jonathan Sommer, a lawyer who had recently represented a woman who’d launched a lawsuit against another gallery, alleging it had sold her a fake Morrisseau. During that trial, one of Morrisseau’s gallerists argued that the work had telltale signs of a forgery: the back of the canvas was signed in black dry brush, which was inconsistent with Morrisseau’s style, and the layers of paint had been applied in a different order. But the defendants called on other experts, including McLeod and a forensic scientist specializing in document verification and handwriting analysis, who testified that the signature was almost certainly authentic. Presented with opposing opinions, the judge ruled that there wasn’t enough evidence to prove it was fake. The owner of the work didn’t want to keep fighting in the courts, but Hearn, a platinum-selling rock star, did. He sued McLeod for $80,000.

To win their suit, Hearn and Sommer knew they’d need to do more than call upon expert witnesses who believed Spirit Energy was a fake. They decided to investigate the provenance of the piece. McLeod claimed that Morrisseau had painted several pieces, including Spirit Energy, while in jail and that he’d given them to a prison guard. But when Sommer asked Correctional Service Canada, he discovered there was no such guard. McLeod had provided a list of previous owners: some of them said they’d never seen the piece, others simply didn’t exist. Sommer and Hearn eventually traced the painting back not to a prison guard but to an auctioneer named Randy Potter, who seemed to have purchased the painting—and many others like it—from a man in Thunder Bay named Gary Lamont.

“It wasn’t about the painting anymore. It was really about the victims of the whole scam.”

When Hearn sued McLeod, a handful of collectors rallied behind the gallerist, including Joseph Otavnik, the owner of several questionable Morrisseaus who had sued Vadas in 2007 for allegedly devaluing the paintings he owned. Since then, Otavnik had launched several more lawsuits against anyone who so much as whispered that his paintings were fake. For the most part, the strategy worked: even experts were scared to take a side. If McLeod was found to be selling fakes, then Otavnik’s Morrisseaus, purchased from his gallery and marked with the same dry brush signature as Hearn’s, would likely be worthless. In 2017, just before the case went to trial, McLeod died. Another one of those Morrisseau collectors, a historian named John Goldi, attempted to get involved in the case to reject the existence of fakes.

In court, Goldi repeated the sorts of arguments contained in Otavnik’s original suit and claimed that Morrisseau’s keepers were trying to corner the market to serve their own economic interests. He also sowed chaos. Hearn says that Goldi and his wife, Joan, slandered their opponents online, publishing inflammatory lies about Hearn and posting pictures of his daughter, who is disabled. They tarnished Sommer’s reputation to the point where the famous Scottish Canadian tenor John McDermott, who also owned a suspected fake, dropped him as counsel. Hearn says the Goldis hissed at him in the courtroom and harassed his witnesses using fake email addresses. Hearn had to hire private security to escort one expert witness, a member of the Norval Morrisseau Heritage Society, to and from court. “It was just this weird, awful, ugly, dark element to what was already a tough thing,” says Hearn.

The court heard from not only art experts but also Lamont’s victims, one of whom retold the story of forging Morrisseau’s work to feed a drug addiction and avoid Lamont’s wrath. By the closing arguments, Hearn had spent much more than the $80,000 he had demanded from McLeod, and Sommer estimates he put in a million dollars’ worth of pro bono work. “It wasn’t about the painting anymore,” Hearn says. “It was really about the victims of the whole scam.”

In early 2018, the judge ruled in favour of McLeod: while he accepted the existence of Lamont’s fraud ring, none of the witnesses could convince him that Spirit Energy was a fake. On appeal, however, another judge ruled that because McLeod had provided fabricated provenance, he had breached their sale contract and therefore defrauded Hearn. “I remember the feeling of a weight lifting off my shoulders that I’d had for ten years,” says Hearn. The judge ordered the McLeod estate to pay him $60,000 in damages. Hearn told them to donate the money to an Indigenous charity instead. They have yet to do so.

Hearn had invited the documentary filmmaker Jamie Kastner to follow the trial in hopes that a movie would publicize Lamont’s forgery ring and prod police to lay charges. The film, There Are No Fakes, also detailed the death of seventeen-year-old Scott Dove, who’d bought drugs from Lamont and was later found dead. After the film was first screened in Thunder Bay, in the summer of 2019, a police officer named Jason Rybak called Hearn and Sommer and explained that he thought portions of the film might help him prosecute Lamont, the leading suspect in Dove’s death. Ultimately, Sommer recalls Rybak saying, there wasn’t enough evidence to indict Lamont for murder but he could build a case around the forgeries instead—something Vadas, Morrisseau’s business manager, had been pursuing for years. In 2007, following Morrisseau’s death, Vadas had reported the fakes to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police; months later, they had referred the case to police in Thunder Bay, who had never laid any charges. “It was a difficult fire to light,” Sommer says about convincing police, “but once it got going, it was a big bonfire.”

In 2023, after a two-and-a-half-year investigation, Rybak and a team of Thunder Bay and Ontario Provincial Police officers arrested eight people in connection to the fake Morrisseaus. The charged included Lamont and his wife, Tkachyk; Morrisseau’s nephew Benji; an art wholesaler named Jim White, who allegedly sold fakes; David Paul Bremner, who is thought to have created fake authentication documents, according to Sommer; and three others, who police say were involved in the forgeries. In December 2023, Lamont pleaded guilty and was sentenced to five years in prison. Police, who called the operation “the biggest art fraud in world history,” have seized more than a thousand fakes; the Morrisseau estate estimates there are thousands more.

It took police nearly two decades to crack down on forgeries of works by one of Canada’s greatest artists. That doesn’t bode well for other Indigenous artists, many of whom deal with fakes on a daily basis. Andy Everson, a Northwest Coast artist, says that people regularly send him links to online stores where his designs, including an Every Child Matters logo, have been stolen and printed onto T-shirts, mugs, and Crocs. “A lot of times, I just ignore it because it’s so pervasive,” he says.

Everson is the primary artist for Totem Design House, a business run by his wife, Erin Brillon, that sells Indigenous-made clothing and art. Brillon says it’s tough to make a living when stores sell knock-offs of their wares at a discount. The replicas, they say, come from Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines and are carved by local artisans paid measly wages, while the middlemen who ship their creations into Canada reap the profits. Some are sold on online arts marketplaces like Etsy and Redbubble. “When people complain or make comments, they block those people,” says Brillon. “And if their ads get taken down, they’ll pop up the next week with a slightly different business name and website.”

In some cases, the forgers don’t fake just Indigenous artwork; they fake entire Indigenous identities. In 2021, Brillon noticed something fishy about an artist named Harvey John. Though John’s bio noted he was Nuu-chah-nulth from Vancouver Island, no one in his supposed hometown knew him, and one art store in Alberta suspiciously described his work as original Haida carvings. Brillon posted about John in a Facebook group dedicated to exposing fraudulent Indigenous art. Its members got to work investigating the supposed Haida artist, ultimately discovering that the persona was entirely fictitious. “There is a long legacy of non-Indigenous people profiting from our artwork,” says Brillon. “How many generations have seen their artworks stolen? From the start of colonization to now, it hasn’t gotten any better.”

Faced with fakes, Indigenous artists have little recourse. They can hire a lawyer and spend thousands of dollars to pursue lawsuits that may not lead anywhere. “The Morrisseau case was the tip of the iceberg,” says Jason Henry Hunt, a Kwagiulth carver on Vancouver Island who frequently finds phony copies of his work being sold online. “It can’t be that every single case of forgery has to be this multi-, multi-, multi-million-dollar thing—including who knows how many different branches of government and the RCMP and the courts—just to prove something that is relatively obvious to everyone.”

Since the summer of 2022, Patricia Bovey, the first art historian to serve as a Canadian senator, has pressured the federal government to set up a legal fund to support Indigenous artists. “I’m devastated for the artists who are losing their rights,” she says. “I’m devastated for their loss of income and the blow it’s taking to their professional credibility.” Though Bovey was forced to retire from the Senate when she turned seventy-five last year, she is still lobbying Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s cabinet to institute changes that would protect Indigenous artists: tightening importation rules to stop counterfeit art at the border, training customs agents to identify fakes, and advocating for changes to the Copyright Act that would require art resellers to remit 5 percent of their profits to the original artists or their estates, ensuring that Indigenous artists are compensated every time a non-Indigenous dealer or auctioneer sells their works. In 2022, the federal government promised to incorporate resale rights into the Copyright Act, but it has yet to do so. In fact, it has implemented none of Bovey’s proposals.

But it may be a question of resources or priorities: the RCMP and Sûreté du Québec’s joint Integrated Art Crime Investigation Team, a once four-officer unit tasked with policing art fraud and theft nationwide, is now defunct. “There is no consideration within the RCMP to create a federal art-fraud investigation unit,” the RCMP told the CBC last December. By comparison, France enforces resale rights and funds a roughly thirty-agent art-fraud and theft police unit. The United States’ Department of the Interior, through the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, can prosecute producers of fake Indigenous art. Canada, meanwhile, has few tools to detect, investigate, and prosecute inauthentic art, meaning that fakes of all kinds continue to flood the market. Last January, for example, the public learned that three works in the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia believed to have been painted by the folk artist Maud Lewis were, in fact, forgeries, according to the CBC.

The upshot is that Indigenous artists are robbed of the recompense they’re owed. Hunt comes from a long line of carvers that includes his uncle, Richard, whose work has been replicated by forgers in Eastern Europe using 3D printers. Hunt worries that the ubiquity of fakes will stop younger artists from taking up the craft, endangering yet another facet of Indigenous culture. “In our village, my brother and I are the two youngest guys making a living as artists—and I’m fifty,” he says. “It’s a hard way to make a living to begin with, let alone having to compete with all the fraudulent stuff that’s out there.”

“What we need at the core level,” says Cory Dingle, the executive director of Morrisseau’s estate, “is legislative change.” He says that Canada is paying for its inaction on the international stage. European galleries, he says, may become scared to display Canadian artists, concerned that their reputations will take a hit if the works turn out to be fake. “My counterparts phone me from Germany and France and say, ‘What the fuck is going on in Canada?’”

Though some of Morrisseau’s forgers have been arrested, many of the fakes they made remain at large. This past January, Ontario Provincial Police took Salmon Life Giving Spawn, a suspected counterfeit, off the walls of the provincial legislature. Two weeks later, McGill University removed a supposed Morrisseau, Shaman Surrounded by Ancestral Spirit Totem, from a campus library and launched an investigation into its provenance. Even as investigators clean up the Morrisseau market, a cloud of uncertainty continues to hang over his legacy.

“The thing that deserves more attention is Norval himself: who he was and what he was trying to teach people,” says his friend Bryant Ross. “But the conversation always goes to the forgeries.” Today, many auction houses, including Heffel, refuse to sell his work, not only because there are still thousands of fakes out there but also because, for a long time, selling Morrisseaus meant getting entangled in a dark web of shady characters and intractable lawsuits.

Now, however, there is progress. Lamont’s guilty plea means that no one can deny the existence of fakes anymore. And following the arrests, Morrisseau’s biological children decided to work together with Vadas to restore their father’s legacy. (In the past, Morrisseau’s biological children and Vadas have had a tenuous relationship; at one point, they accused him of taking advantage of Morrisseau, as reported in the CBC. They have since reconciled, according to Vadas.) There is now a torrent of Morrisseau-related projects in the works. Queen’s and Carleton universities have mounted new Morrisseau exhibitions. Carmen Robertson, a Carleton art history professor and member of the Norval Morrisseau Heritage Society, is part of a research team compiling a book, due out in 2025, featuring Morrisseau’s pre-1985 work; a book on the latter half of his career will follow. “Morrisseau’s sense of genius—what he honestly accomplished as an artist, his visual language, what he did with his subject matter—has been watered down or tainted in such a way that, when you google his art, you often see things that are not by the hands of that artist,” says Robertson. “And so I hope that we can restore a sense of what his aesthetic power was and continues to be.”

Dingle, the head of Morrisseau’s estate, is working on the most ambitious effort of all. Not long ago, the founder of Toronto’s Museum of Inuit Art reached out to him, proposing the creation of a new gallery of Morrisseau’s works, on the property of the city’s Metropolitan United Church. The gallery is meant to be a concrete act of reconciliation, a symbolic bridge between the church and Indigenous people—something that would have aligned with Morrisseau’s mission. “Why am I alive?” Morrisseau once said. “To heal you guys who’re more screwed up than I am.” If all goes as planned, the gallery will include a collection of unseen Morrisseaus that his estate kept hidden during the decades-long forgery debacle. Visitors will no doubt marvel at these never-before-seen works. And at least a few of them will quietly question whether they were really painted by Norval Morrisseau at all.

Correction, April 11, 2024: An earlier version of this article stated that an artist working with Toronto’s Metropolitan United Church had reached out to Cory Dingle about creating a new gallery of Norval Morrisseau’s work. In fact, it was the founder of the Museum of Inuit Art who proposed the idea. The Walrus regrets the error.