Here is the happy part: For more than four years, a funky-looking spacecraft did something remarkable. It was in many ways just another robot, a combination of hardy materials, circuits, and sensors with a pair of solar panels jutting out like wings on an insect. But this particular robot has listened to the ground shake on Mars. It has felt marsquakes beneath its little mechanical feet.

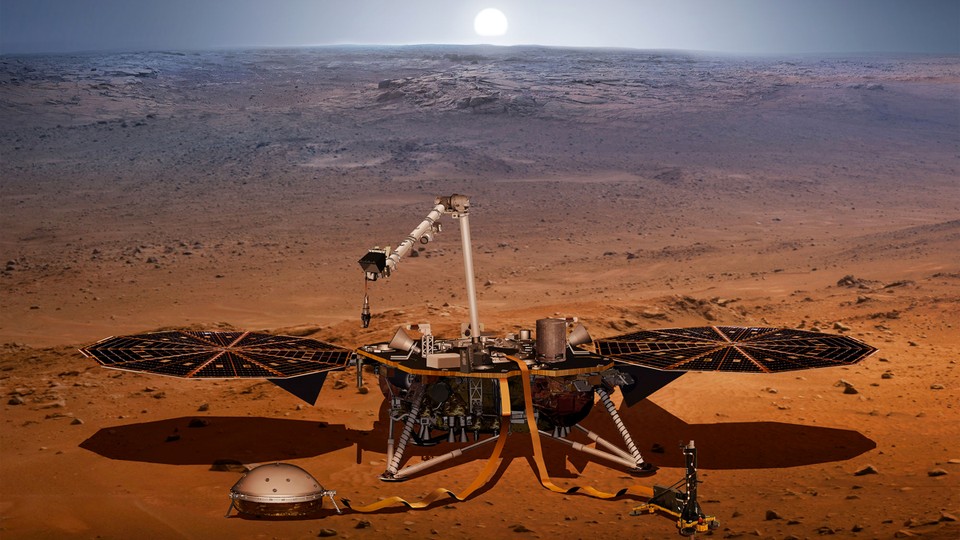

NASA and European space agencies designed the spacecraft to study these Martian quakes in detail. Mission managers, in their seemingly endless capacity to invent twisty acronym names for space-bound projects, called it Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport—or InSight, for short. Once on Mars, InSight couldn’t go anywhere; it was a lander, not a rover, so the mission was rooted to the spot where it touched down. Every picture the robot beamed home showed the same dusty, cinnamon-colored expanse, but behind the understated photography, InSight was waiting for the marsquakes to roll in.

Here is the sad part: InSight stopped calling home this month. The mission, NASA concluded last week, had run out of energy. (Who says space exploration isn’t relatable?) Dust has been accumulating on those bug-like solar panels all year, diminishing the lander’s power supply until it couldn’t even wake up.

The end of InSight prompted a round of doleful news coverage, with sweet praise for the little lander. We humans can’t help but anthropomorphize robots, especially the ones we have dispatched to the other worlds in our solar system, tasked with absorbing all the wonder for us until they no longer can. (It didn’t help that when the time came, NASA tweeted from the mission’s account in the voice of the dying lander, “My power’s really low, so this may be the last image I can send.”)

The sappy reaction felt extra poignant this time around. A lander is less flashy, and perhaps less interesting, than a rover. It is easier to create a compelling, heartwarming story about a machine that roams the surface of an alien world and inspects the landscape with the delight of a small child finding a cool rock. It is easier still to fawn over a tiny helicopter on Mars, which flew for the first time last year. Even as the stationary InSight did historic work—studying the rumble of a world beyond Earth for the first time since the Apollo astronauts took seismometers to the moon—it seemed like a supporting character in the cast of Mars missions. There’s no space robot I’ve wanted to anthropomorphize more.

Mars wasn’t easy on InSight. Take the case of the soil snafu. The lander arrived on Mars in late 2018 with an instrument designed to hammer into the surface to measure the interior’s heat. But no matter how hard InSight (and its stewards back home) tried, the instrument wouldn’t sink into the ground. Based on their understanding of Mars’s terrain, scientists had expected InSight to encounter fine, sandy soil at its landing site in Elysium Planitia, a flat plain near the equator. Instead, the soil was clumpy, providing little friction for the tool to work properly.

Scientists and engineers spent two years trying to maneuver the instrument deeper beneath the surface, even telling InSight to use its robotic arm to help bury the instrument—a task that the arm wasn’t meant for. But the tool remained stuck—seriously, so relatable!—and by early 2021, NASA was forced to give up on this part of the mission. “It’s a huge disappointment,” Sue Smrekar, the deputy principal investigator of the InSight mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told me back then.

InSight also suffered from a bit of a paradox: The very conditions that permitted it to do its work also eventually depleted its energy. (Again, I feel you, InSight.) The mission’s seismometer was so sensitive that vibrations produced by the Martian wind could obscure a gentle tremor. That made the Martian summer, with its calmer weather, the best time to catch quakes. But windless days also allowed dust to accumulate on InSight’s solar panels and blocked much-needed sunlight.

The mission didn’t come with any dust-removing technology. InSight’s human caretakers occasionally instructed the robot to use its robotic arm to sprinkle the solar panels with dirt, which, when swept away by the wind, took some of the smaller, stickier pieces of dust with it. In space exploration, mundane mechanisms can quickly become complicated, very expensive hardware that must be tested relentlessly here on Earth if they stand a chance of working on an entirely different world. Plus, interplanetary missions must travel light. Instead of investing in windshield wipers, mission managers chose to make the solar panels as large as they could so that the spacecraft could soak up more rays, even as the dust that would be its downfall began to pile up.

Despite the soil saga and its battery woes, InSight kept listening for marsquakes, detecting its largest earlier this spring, at a magnitude of 5. (On Earth, such a quake would rattle dishes and break windows.) InSight even detected the vibrations produced when meteoroids fell from the sky and hit the surface. And its readings clued astronomers in on the fact that Elysium Planitia is one of the most geologically exciting places on Mars: A recent analysis found that a plume of hot material is bubbling up through Mars’s mantle like “hot blobs of wax rising in lava lamps,” lifting part of the plain in a noticeable peak.

NASA says that it will continue to listen for a signal from InSight, but the lander is unlikely to pipe up again. The robot will become, like other Mars missions before it, a curious piece of junk courtesy of the aliens next door. From its perch, InSight explored Mars in a way no other mission to the red planet had done before, and the data will benefit future missions, including those that may someday include robots and people. The spacecraft felt something fascinating and truly alien on our behalf. Over a trying few years, it did its best.