Within a month of the first community exposure to Omicron in Aotearoa New Zealand, the variant has already become the dominant strain of COVID-19.

We are yet to see the rapid and steep rise in new Omicron cases that has been predicted. This could be because of asymptomatic transmission, but it is equally likely because public health measures included in the first phase of the “stamp it out strategy” have been effective.

For now, managed isolation and quarantine (MIQ) at the border is successfully stopping hundreds of cases from entering the community. While MIQ may soon change in purpose, border restrictions may not lift until the Omicron wave passes.

The country-wide return to red settings under the COVID-19 protection framework has bought New Zealand time to learn from experiences abroad. The most challenging phase is yet to come but New Zealand could be well placed to tackle it.

The best way forward is to limit widespread transmission for as long as possible. This reduces opportunities for the virus to replicate, which is when mutations occur, potentially extending the pandemic.

What we know about Omicron

Omicron is more transmissible than earlier variants. New Zealand can expect a rapid and steep rise in infections, especially as we’ve already had several potential superspreading events.

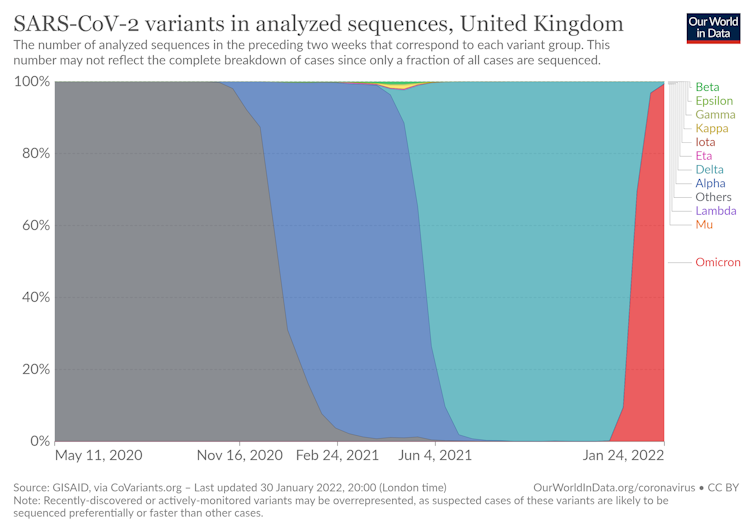

As shown below, Omicron quickly replaces earlier variants.

Omicron’s transmission advantage is thought to be due to its ability to evade immunity (acquired through infection or vaccination) and quickly infect the upper respiratory tract.

The risk of reinfection also appears higher than for Delta, particularly in the unvaccinated and those with lower viral loads during previous infections.

Read more: What we know now about COVID immunity after infection – including Omicron and Delta variants

Symptoms to watch out for

Omicron symptoms include a runny nose, headache, fatigue, sneezing and a sore throat.

However, New Zealand’s high vaccination rates mean some people may not have any symptoms at all. The danger here is that they will still be able to pass on the virus to others, unaware they have Omicron.

It is best to assume that any symptoms, especially a sore throat, are COVID-19 until proven otherwise through a test. For Omicron, this may require saliva swab tests as recent evidence suggests they are more sensitive than nasal swabs because the viral load peaks earlier in saliva than nasal mucus.

By testing and isolating, we can avoid spreading it to others who may be at higher risk of severe illness.

Compared to Delta, Omicron has caused lower hospitalisation and death rates in many countries. This may be because it reproduces in the upper respiratory tract instead of the lungs.

Omicron is also meeting populations with immunity acquired through previous infection or vaccination.

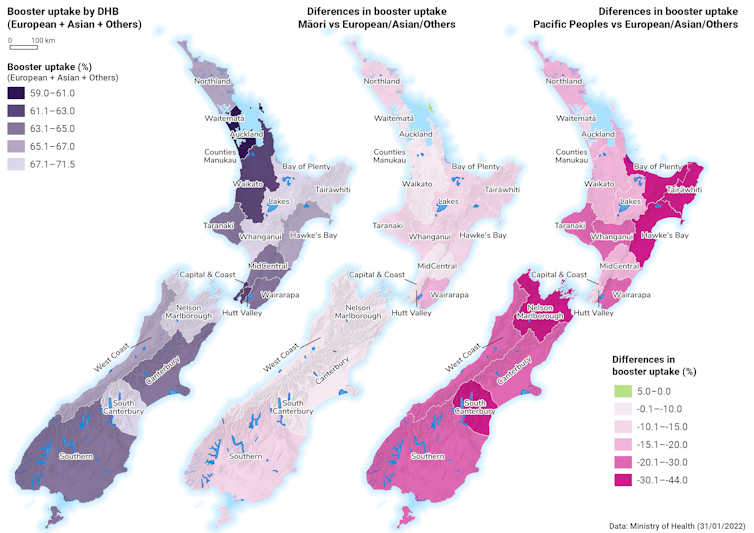

In New Zealand, 67% of eligible people have now received their booster, which offers high levels of protection from hospitalisation and death. Boosted individuals are up to 92% less likely to be hospitalised with Omicron, compared with unvaccinated people.

Vaccination is especially important in New Zealand as we have had minimal prior exposure to COVID-19 in the community.

Where to from here

Omicron is a “double-edged sword”. It is vastly more transmissible but less severe. However, it is not a mild infection and there is no guarantee the next variant will be less severe.

In a poorly controlled outbreak, a small percentage of a large number of cases risks overwhelming healthcare systems, increasing inequities and disrupting essential services.

Healthcare workers are already over-burdened and exhausted from previous outbreaks, which have distracted from other services and exacerbated entrenched inequities.

There are several things each of us can do:

Anybody eligible should prioritise getting boosted

we should all continue using the COVID-19 tracer app

we should keep indoor spaces well ventilated by opening windows and doors

mask wearing remains important, especially where physical distancing is difficult.

and anybody who feels unwell, should get tested and isolate.

Vaccinating children

As children return to school, we need equitable vaccinations and ventilation.

Data out of Australia indicate children aged five to 11 tolerated the vaccine well, with fewer side effects than adults.

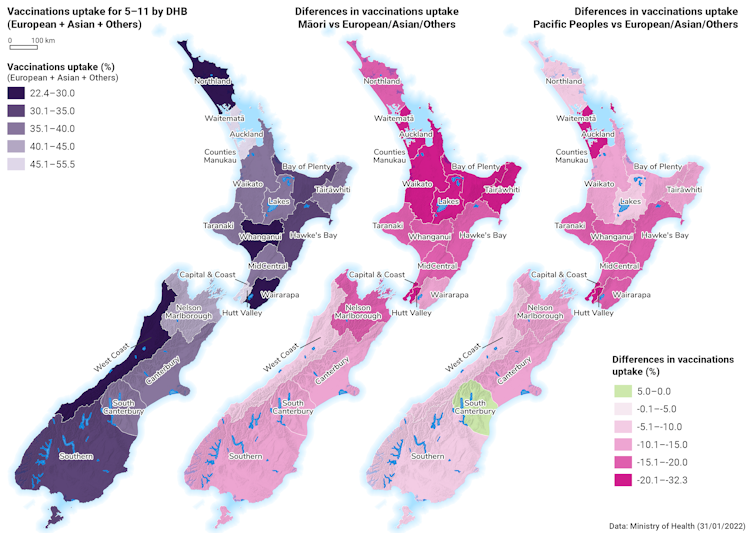

Unfortunately, our analysis, along with other evidence, documents a concerning trend with lower childhood vaccination rates for Māori and Pasifika, as well as large variation between regions.

This is concerning as some countries, including the US, have seen increases in childhood hospitalisation rates for COVID-19. In the UK, one in eight pupils have missed school as COVID-related absences rise.

Read more: Despite Omicron arriving, keeping schools open as safely as possible should be the goal

The success story of the Delta outbreak

Unfortunately, there’s been little time to celebrate the rather remarkable demise of Delta. Even as Auckland opened up, hospitalisations and case numbers dropped.

Summer will have helped as people spent more time outdoors. However, public health measures such as border closures, managed isolation and quarantine and contact tracing have no doubt helped stamp out much of Delta, allowing a relatively normal summer holiday period for many.

Continuing to keep Delta low also means we should not have to deal with a “double epidemic”.

This success may also fill us with some hope that, just perhaps, we might be able to avoid the worst of Omicron during this next phase of the pandemic response, with robust and continually refined public health measures in place.

Dr Matthew Hobbs receives funding from New Zealand Health Research Council, Cure Kids, A Better Start National Science Challenge and IStar. He was previously funded as a postdoctoral researcher by the New Zealand Ministry of Health.

Dr Anna Howe receives funding from the Health Research Council. While not the principal investigator she has been involved in research projects funded by GSK and was the first KPS Research Fellow. She is affiliated with the Immunisation Advisory Centre.

Dr Lukas Marek has previously received funding from the Ministry of Health, New Zealand Health Research Council, Cure Kids and National Science Challenges.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.