Volcanoes were erupting on the Moon as recently as 120 million years ago, evidence collected by a Chinese spacecraft suggests. Until the last few years, scientists had thought volcanic activity ended on the Moon around 2 billion years ago.

The findings, published in Science, come from analysis of lunar rock and soil delivered to Earth by China’s Chang'e 5 spacecraft in 2020. While these results are difficult to reconcile with the accepted history of lunar volcanism, it’s possible some areas of the Moon’s interior were more enriched in radioactive elements that generate the heat that drives volcanic activity.

The region where Chang'e 5 landed, called Oceanus Procellarum, may be one such area where rocks were enriched in these heat-producing elements.

Volcanism is a major way in which all rocky planetary bodies lose their heat. The rocky bodies in our Solar System are Earth, Venus, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter’s satellite Io, and Earth’s satellite, the Moon.

All available evidence suggests that Venus is currently volcanically active. On Mars, we can date the ages of formation of large lava flows by counting the numbers of impact craters on these flows.

This crater-counting technique relies on the fact that craters form randomly and uniformly across planetary surfaces, so highly cratered terrains are considered older. The results suggest that Mars, which is half the size of Earth, is volcanically active every few million years.

This is expected, because larger bodies conserve heat better than smaller ones. On this basis Mercury, which is a third of Earth’s size, and our Moon, a quarter the size of Earth, should have been volcanically dead for about 2 billion years.

The same should be true of Io, which is similar in size to our Moon. However, tidal forces generated by gravitational interactions with Jupiter give Io an additional, strong heat source. Io is very volcanically active as a result.

The Moon’s dark areas

Most eruptions on the Moon took place near the edges of giant depressions formed early in the Moon’s history by asteroid impacts. Lava flooded the interiors of these basins to form the dark areas on the Moon’s near side. These areas are call maria (singular mare), the Latin for seas, because the flat sheets of lava were mistaken for expanses of water by early observers.

Analyses of the composition and age of samples returned from these mare areas by the six Apollo missions and three Soviet robotic probes were consistent with the belief there had been no geologically recent volcanic activity on the Moon.

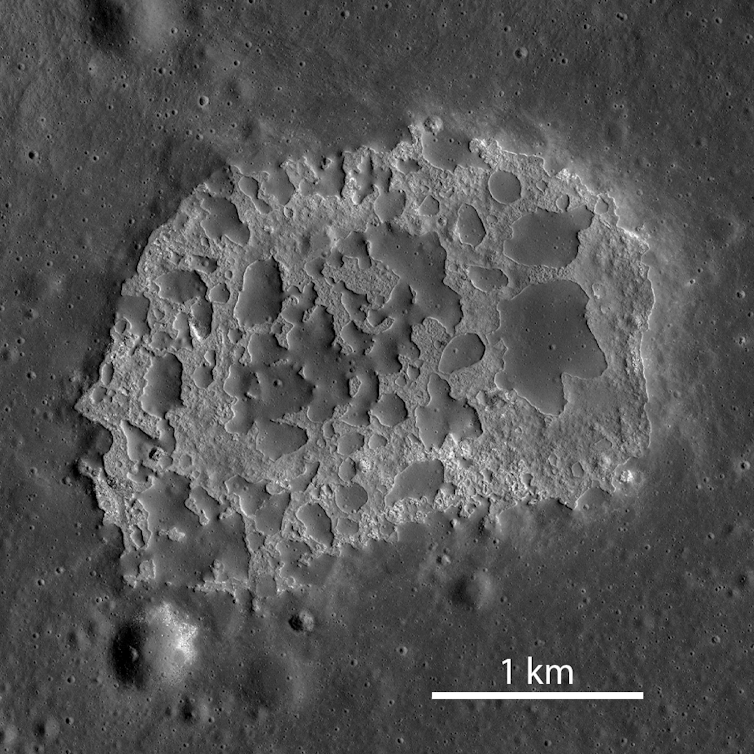

This understanding persisted until very high-resolution images of the lunar surface from the US Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission became available following the mission’s launch in 2009. Counts of the numbers of very small impact craters revealed a lack of craters in some volcanic areas with unusual surface textures, named irregular mare patches (IMPs).

The simplest explanation for this was that these IMPs were young, typically about 100 million years old. This is 20 times younger than the 2 billion-year youngest age that had been expected.

In an attempt to reconcile these observations with the accepted history of lunar volcanism, it was pointed out that the lack of any atmosphere on the Moon would make eruptions there significantly different from those on Earth. The lack of confining pressure would have allowed erupting lavas to release almost all of the gaseous compounds dissolved in them, allowing some lava flows to contain very large numbers of gas bubbles – to the extent of being a foam.

Meteoroid impacts into this soft foam would produce much smaller craters than in solid rock, thus causing the crater-counting method to give ages that were too young.

This issue has seen much debate, and the best way to resolve it is the return of samples to Earth for detailed laboratory analysis. Chang'e 5 brought back samples from a very large lava flow which was already known, from crater-counting, to be relatively young in geological terms.

Initial analyses of many fragments of the lava were consistent with the long-accepted theory that lunar volcanism stopped 2 billion years ago. However, closer examination of the Chinese samples, as described in the new Science paper, focused on some of the smallest fragments – the majority from rock shattered and melted into droplets by meteoroid impacts.

Three of these 3,000 droplets were identified from their detailed chemistry as volcanic in origin, and are only 120 million years old – very similar to the young ages inferred for IMPs elsewhere on the Moon.

Lunar eruptions

Lunar eruptions should have involved high lava fountains like those commonly seen erupting in Hawaii, for example. While most of these droplets would have accumulated into lava flows, some would have been thrown out for tens of kilometres to other parts of the Moon’s surface.

The three “volcanic droplets” identified in the Chang'e 5 sample were probably not erupted from the same vent as the bulk of the rock and soil delivered to Earth. This would explain why these droplets are much younger than the lava flow at Chang'e 5’s landing site.

These three glassy droplets are the first physical evidence we have for anomalously recent volcanic activity on the Moon. There would have to have been much higher concentrations of heat-producing radioactive elements in some areas than others for volcanic activity to have occurred as recently as the new results imply. So, these findings could prompt a major revision in our understanding of how the Moon developed.

Lionel Wilson has in the past received funding from the Leverhulme Trust for work on lunar volcanism.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.