Lana Wachowski understands film aesthetics better than anyone.

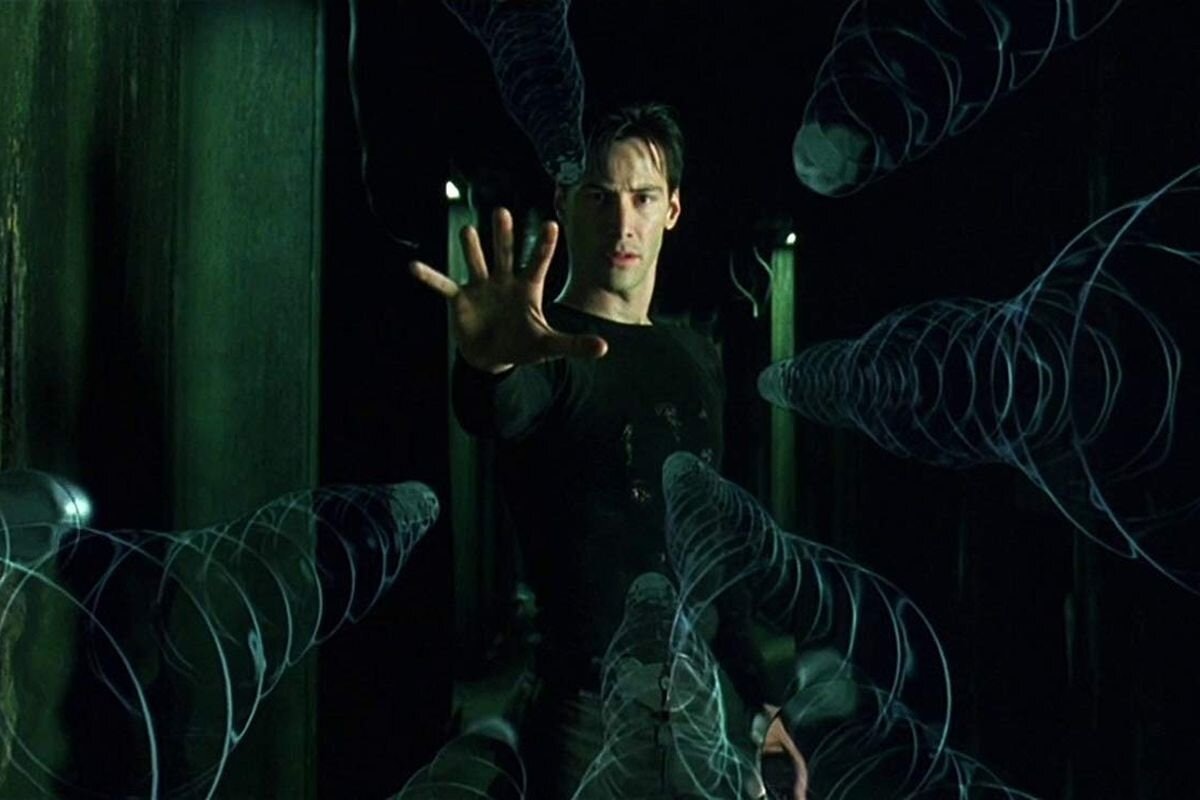

With the relentlessness of a great white shark, she vigorously hunts for a new aesthetic (the way form and color and sound and design create an emotional experience) for every new project. Think of all the elements you associate with The Matrix ‘99:

- The perfect green tone of the matrix

- The destabilized relationship of space and time visualized with bullet time

- The total lack of establishing shots and the claustrophobia of the unnamed city

- The feeling of cool frozen in amber 1999

- The perfect structured fight sequences designed by Yuen Woo-ping

- The entire, perfect tone

These elements (and more) combine to make the very clear look and feel that we all recognize as “The Matrix franchise.”

The Matrix Resurrections doesn't have any of them.

Twenty-two years ago, The Matrix used bullet time to make people experience what it might mean to decouple space and time from their constraints, a breakthrough that felt like waking up to a whole new level of reality. The Matrix of 2021 has to figure out how to depict cinematically the feeling that two decades later, all of us are still here in this faltering, messy reality.

Think of the game designer-turned-agent in Resurrections who keeps saying “Bullet time!” over and over, filing off the edges of an idea that was once mind-boggling only to become a joke in Shrek. Or as Jessica Henwick’s Bugs says, “They took your story, something that meant so much to people like me, and turned it into something trivial. That’s what the matrix does. It weaponizes every idea. Every dream.”

Within seconds, Resurrections makes it clear this rejection is a deliberate assault. The first shot, a street puddle with an upside-down reflection of a SWAT Team approaching in slow motion, is stunning and powerful. Then a cop boot stomps down on the puddle, destroying the beauty under its heel. We are not just through the looking glass — the mirror is smashed.

Lana Wachowski’s anti-aesthetic

In Resurrections, the first trilogy’s shiny-cool aesthetic is continuously and resolutely smashed by its own creator. It’s Lana Wachowski using an anti-aesthetic and intentional ugliness to express the current state of reality and to question how the aesthetic of The Matrix franchise may have turned out to function like the matrix itself.

“There’s an aesthetic genealogy to The Matrix,” Lana once said in a 2014 talk at the DePaul University School of Cinema and Interactive Media’s Visual Artists Series. ”Aesthetics are like the DNA of art… it's a reflection, it's the way that artists reveal themselves and their choices aesthetically.”

So why is she compelled to lose the bullet time? The green-tinted film grain? The Yuen Woo-ping fight-scene perfection?

Because Lana, like Neo, is compelled to resist control, to courageously reject her own aesthetic in favor of following the truth. As Toby Onwumere’s Seq says at the start of Matrix Resurrections, “Why use old code to mirror something new?”

“Human suffering is so lucrative we can no longer even witness a matrix that feels cool.”

This is not just Lana saying her original story was twisted out of her grasp by its sequels, by its corporation, by its fans (though that may be part of it). It’s her looking deeply into the mirror and seeing herself — the Architect, the Creator — as part of the matrix simulation, the actual forces of control and capital and destabilization in our world. It’s a critique that philosopher Jean Baudrillard, whose book Morpheus quotes to Neo, flung at the movie in 2003:

“The Matrix is surely the kind of film about the matrix that the matrix would have been able to produce… Basically, its dissemination on a world scale is complicit with the film itself.” That is, the matrix, if it were real, would obfuscate its actual tactics by making the movie The Matrix.

Which is exactly what the matrix, in Resurrections, has made Neo do. (Although here, it’s a video game, to better explore the hold it has on our minds and bodies.)

So now Lana, a constantly evolving filmmaker, wants to deconstruct the original’s style. She unrelentingly reminds us of the old franchise’s aesthetic by having it show up as the memories — the nostalgia — of the characters so that we have an emotional reaction to the old footage (longing, bittersweet joy, frustration) while questioning why she’s stripped that bold look away in favor of the bland color range of any mundane drama.

Wachowski even has her villain, Neil Patrick Harris’ The Analyst, explain this aesthetic choice. He created a matrix with more ugliness as a systemic tool to optimize efficiency. To the Analyst, human suffering is so lucrative we can no longer even witness a matrix that feels cool.

And yet, Lana knows that people will freak out.

“People always hate it when you assault a dominant aesthetic,” she said in that same 2014 talk. “People feel almost violent.”

Rejecting the “franchise aesthetic”

In 2021 the dominant mood is frustration and the dominant aesthetic is the franchise aesthetic. Filmmakers come into a universe — whether in a movie installment or an episode of a series — and they adapt or conform their personal vision into the aesthetic of the franchise. The genius of, for example, Marvel movies is that even the most creative ones still feel like a “Marvel movie.”

As a free-thinking artist within a franchise about rejecting systemic control, Lana must reject the dominant franchise aesthetic. She wants us to compare her movies, to have an emotional reaction (longing, bittersweet joy, frustration), and to question why she is making us do that.

“We miss the feeling of the older, cooler prison.”

We are watching The Matrix from within the matrix. We miss the feeling of the older, cooler prison. (Isn’t it weird that all the rebels want to take down the matrix, yet every time they go there they dress for a party, skinned like their personal aesthetic within the prison is the most important of freedoms?) And when The Matrix Reloaded’s Merovingian (Lambert Wilson) shows up, this once-slick sophisticate, now scruffy and miserable, blames Neo for the terrible aesthetics of this modern world.

“We had grace. We had style!” the Merovingian screams. “Originality mattered! You gave us face-zucker-fuck and Cock-me-climatey-Wiki-piss-and-shit.” (Monica Bellucci is too beautiful and perfect to undergo this degradation — she must have slipped out to some other node a long time ago.) Yet even though his fight with Neo is one of Resurrections' better fights, the Merovingian’s bizarre, shrieking dialogue is the most riveting element of the scene.

Matrix Resurrections is a love story

Resurrections isn’t that interested in fighting. The love story is the draw. Where the key image of The Matrix ‘99 is Neo bending backward to avoid bullets, here it’s Tom Anderson leaning forward to hear Carrie-Anne Moss’ Tiffany talk about her life. Because Neo had to be pulled out of the matrix before he could fall in love, we never before got to see these two in a love story that felt like our own lives: a successful but depressed man in a San Francisco coffee shop talking to a mother-of-two in denial about her own needs. The scene is shot simply – shot, reverse shot, Steadicam two shot – but it feels electric. It’s jarringly honest, more like a moment in an Eric Rohmer or Richard Linklater film than something you’d see in a science-fiction action sequel.

Compare the coffee shop scene to Resurrections’ lackluster Tokyo train fight. It’s clear that to Lana, the real action in this movie is human connection. Lana strips back the Matrix aesthetic in search of what’s beyond the desert of the real. What remains is love.

When I first tweeted my thoughts about Resurrections, some people responded with variations of, “Just say you like a bad movie.” But this isn’t about good and bad. This is about looking at the aesthetics and asking why the film is how it is. Good and bad is a silly binary to put on any film, especially one that rejects binaries over and over again.

So what’s left after Lana’s assault on her own franchise? The love for a woman, the love of a woman, and the power of that woman in love.

After Trinity becomes fully awakened, the film finally transforms into something unmistakably cool: a big budget, high contrast zombie movie with Trinity in control as she and Neo speed away on a motorcycle while bodies fall around them — literal suicide bombs launched by the unhinged Analyst. (I use “zombie” movie as another example of aesthetic choice. Lana borrows equally from the mood of Lamberto Bava (backlit smoke, glowing eyes) and the speed of WorldWar Z, gesturing at the literal curse of a “resurrection.”)

At the very end, once Trinity is integrated, Lana chooses a new and exciting aesthetic that recalls another Baudrillard quote which Lana Wachowski almost certainly came across as well. Speaking of men’s imaginations, he says:

“We have dreamt of every woman there is, and dreamt too of the miracle that would bring us the pleasure of being a woman, for women have all the qualities — courage, passion, the capacity to love, cunning — whereas all our imagination can do is naively pile up the illusion of courage.”

All of Resurrections is building toward that moment of courage, a climax where Trinity and Neo dare to leap off a building to prove to themselves that their memories of the matrix — and of their love — are real. And yet, even here, Lana refuses epic CGI wizardry in favor of two actors dangling on wires above a cityscape: The simple stripped-down joy of seeing Keanu and Carrie-Anne holding hands in the air, a human connection depicted at mythological heights.

The Matrix Resurrections is playing in theaters and on HBO Max