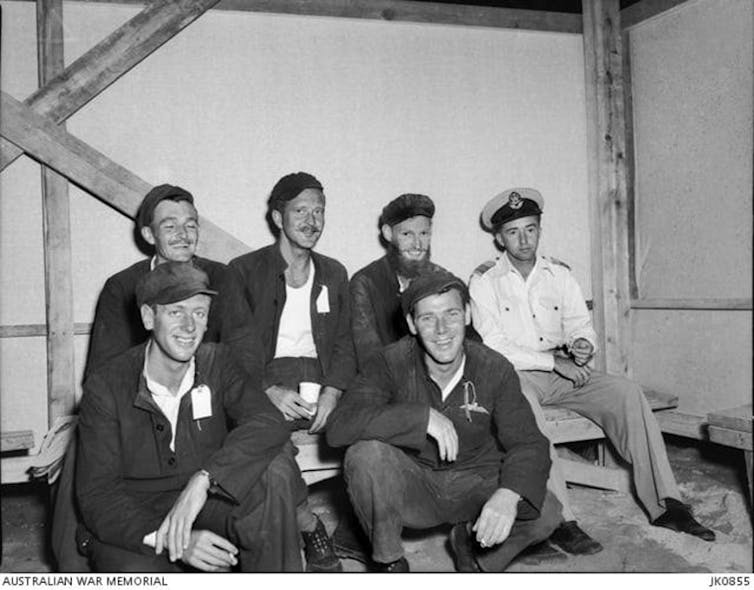

In the collection of the Australian War Memorial there is a photograph of four men in a North Korean prisoner of war camp, taken in the winter of 1952-3. Australian airman Ron Guthrie is in the group. He had been in captivity since August 1951.

More than 17,000 Australians took part in the Korean War, which began in June 1950 as a civil war between North and South Korea and quickly erupted into an international conflict involving China on the north side and the United States on the south. In Chinese, this war is known as the “resist America, support Korea” war.

On 27 July 1953, 70 years ago today, hostilities came to an indefinite halt with the signing of an armistice.

In this bitter, destructive and still unresolved conflict, one of the greatest challenges for both sides was how to deal with the weather. In the summer, men collapsed from the heat and humidity. Weapons became difficult to handle, blistering the hands.

Even worse were the winters. The men in this photo are wearing thickly padded clothes that would help them survive the extreme cold. A line in the 1970s TV series MASH sums up the likely weather conditions at the time: “The temperature is now two degrees below zero [°F]. Tonight’s forecast is cold, with a good chance of bad weather tomorrow.”

Australians had arrived in Korea unprepared for these conditions. They were initially helped out by the Americans and in due course, supplied with their own fit-for-purpose uniforms: a string vest, thick fleece underclothing, a heavy jersey, and windproof combat jacket and trousers under a fur lined parka. All this, together with a down sleeping bag, cost over £100, (around $4000 in buying power today).

Clearly, the four POWs in the photo are not dressed in these made-in-Australia outfits. With the possible exception of the shoes, what they are wearing is not too different from ordinary dress worn by men in China at that time: a high-collared jacket with inset sleeves and five buttons paired with shapeless but nonetheless Western-style trousers, tailored at the crotch.

In a war dominated on the northern side by the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army, the similarities are not surprising. The prisoners are in fact wearing a variety of what foreigners would come to call a “Mao suit”. In Chinese it fits into a category of clothing called zhifu, or uniform.

Read more: North Korean POWs seeking last chance to return home after decades in exile

Mass mobilisation of sewing labour

What is a Mao suit? The term was first used to describe the relatively undifferentiated clothing of people in China during the Mao years – “all dressed in blue boiler suits” in the view of foreigners, although a closer look would show fine gradations in the clothing system. There was a large social distance between the well-tailored suit of fine wool worn by a high official and the roughly-made ensemble in homespun cotton worn by a man on the street.

The fitted, military-looking jacket of the Mao suit resonates both with the longer coat worn by India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and with the stalinka, or Stalin tunic. These items of clothing were all products of global militarisation in the 20th century.

The Chinese variant can be traced to a Japanese-influenced style of military jacket worn by “Father of the Republic” Sun Yatsen, China’s most significant political leader before Mao Zedong.

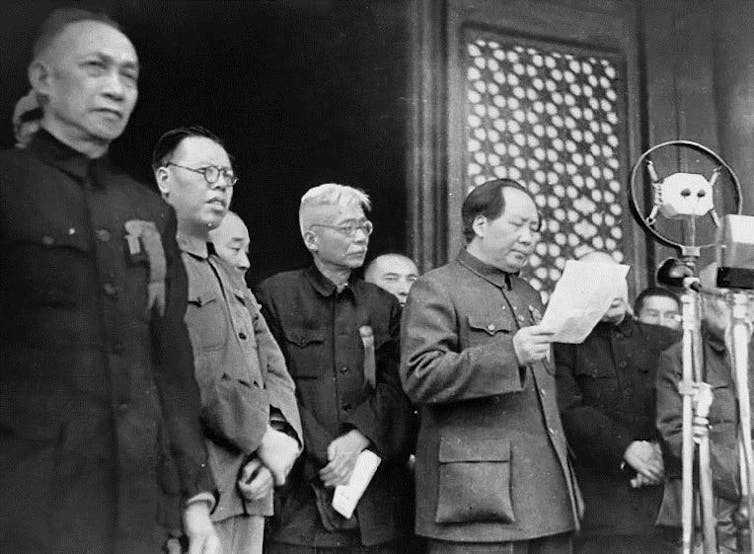

Mao himself set the sartorial tone for Communist China by wearing a jacket in the Sun Yatsen style when he announced the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

The altered appearance of the crowd in any Chinese town after 1949 was one of the most immediate effects of regime change. Both the Chinese long gown and the Western suit were abandoned. Clothing regulations for employees in the state sector established the Sun Yatsen jacket or its poor relative, the “People’s jacket”, as standard dress.

Across China, tailors started cutting up old clothes to fashion these new-style garments. Much of this activity was undertaken while the Korean War was in progress.

For the civilian population, the provision of this new sort of clothing (literally xinyi or “new clothes”) was undertaken piecemeal, often by newly trained housewives given crash courses in the sewing and vocational schools that mushroomed across China in the early 1950s. For provisioning the armed forces, mass mobilisation of labour was required.

Vast quantities of clothing were required very quickly to outfit the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army. In July 1950, normally a slack month in clothing production, four regional military administrations were ordered to supply 340,000 cotton padded uniforms and comparable or greater numbers of shoes, vests, and greatcoats. Gloves (cotton-padded mittens) and socks were needed in greater quantities again.

In the longer-term, skills acquired in the production of army uniforms (fitted garments with pockets, belt hooks, buttons, buttonholes and other novel features) would be applied to the mass production of civilian wear, which was constructed along similar lines.

The huge labour reserves available in China failed to avert a crisis in the supply of winter uniforms in the early months of the war. The Chinese clothing industry at that time was under-mechanised. Most clothes were still made at home or in the corner tailor shop. A sewing-machine industry was only just being developed. Cotton fields were only just being recultivated in wake of years of turmoil during the war against the Japanese (1937-1945) and the ensuing Civil War (1946-1949).

Accordingly, when the People’s Volunteer Army arrived in Korea, they were no better equipped than Australians. As summer turned to autumn, temperatures dropped precipitately. On the front, men cut up their bedding for protective clothing. In the winter, frostbite began to take its toll. Soldiers lost fingers, toes, noses and ears. In the decisive Battle of Chosin Reservoir, some 6,000 Americans and nearly 30,000 Chinese were immobilised by frostbite, 1,000 of them perished from the cold.

By the following spring, clothing production had been ramped up but supply lines were frequently affected by hostilities. Bombings in the Hwacheon Dam area in April 1951 took out a load of 280,000 summer-weight uniform jackets. Soldiers on the front were reduced to stripping their winter jackets of cotton wadding so that they had something serviceable to wear in the warmer weather.

Under these circumstances, clothing prisoners of war had low priority. What protective clothing they had at the time of capture was often taken from them. Cold was their constant companion.

After peace talks began in August 1951, conditions improved and the padded Mao suits of the photograph appear to have become standard issue. Thereafter, one of the main problems was living with lice, which secreted themselves in the seams. In the absence of a change of clothing, lice were almost impossible to eradicate.

Read more: M*A*S*H, 50 years on: the anti-war sitcom was a product of its time, yet its themes are timeless

Unpicking and refluffing

On both sides of the conflict, the punishing winter of 1950-51 concentrated the authorities’ attention on improving the quality of protective better clothing. The technological gap between the US and China is apparent in the outcomes.

Footwear was a prime concern. For the Americans and their allies under the United Nations Command, leather combat boots such as worn in World War II had at first been thought sufficient. By August 1951, the US had come up with an airtight, insulated rubber boot, popularly known as the Mickey Mouse boot on account of its large toe. It did not eliminate the problem of frostbite but with frequent changes of woollen socks sharply reduced its incidence.

The Chinese, too, developed something more effective, with a larger toe, providing room for extra padding. Padded cloth socks were widely used and sewing socks for soldiers became a common domestic pastime.

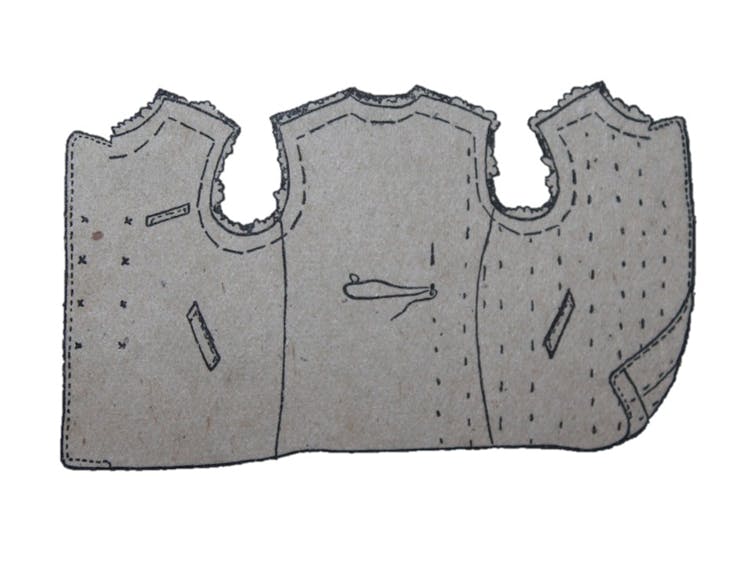

Cotton was core to keeping warm. Insulation of hats, coats, trousers and mittens was provided by inserts of cotton fluff. When newly made up, the proportion of air to cotton provides good insulation in a garment.

Over time, the cotton fluff becomes hard and matted, reducing its effectiveness against the cold. The clothes would need to be unpicked in the summer and the cotton refluffed for service the following winter, an arduous process that in China was a discrete cottage industry.

Fortunately for Guthrie and the other Australian prisoners, this would be their last winter in a POW camp. The armistice was signed in the summer of 1953. An exchange of sick and injured POWs had already taken place in April. The “Big Switch,” entailing an exchange of thousands of POWs from each side, followed in September. It was early autumn. The padded winter “Mao suit” had long since been discarded in favour of its summer equivalent – the plain, blue, high-collared jacket and trousers worn all over China by ordinary working men.

Photographed on release, Guthrie and his companions wear their clothes casually – half-buttoned up, collars gaping over white singlets, caps worn jauntily or backwards. They would shortly change these clothes for their service uniforms. Twenty-nine of the 30 Australians who became POWs returned home, a remarkable survival rate.

Travelling in the opposite direction to Guthrie was a political officer of the People’s Volunteer Army, Xie Zhiqi. At the end of the war the majority of POWs from the People’s Volunteer Army chose to go to Taiwan. Xie was one of the minority who went back to China.

All repatriates to China were interned on arrival and subjected to investigation. Xie was accused of having participated in reactionary activities during his time as POW. Expelled from the Chinese Youth League (a Communist Party organisation) and discharged from the People’s Liberation Army, he had to surrender his army uniform.

He spent the rest of his working life, including seven years of it in a labour camp, wearing the plain blue trousers and high-collared jacket that is now indelibly associated with Mao’s China.

Antonia Finnane is the author of, most recently, How to Make a Mao Suit: Clothing the People of Communist China 1949-1976 (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Antonia Finnane has received funding from the Australian Research Council

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.