Come Monday morning, April 22, the first good meteor shower in nearly four months reaches its peak: The annual Lyrid meteors.

Unfortunately, 2024 will not be a good year to look for these "shooting stars." There is going to be a significant handicap in the guise of a bright waxing gibbous moon, just one day before full phase.

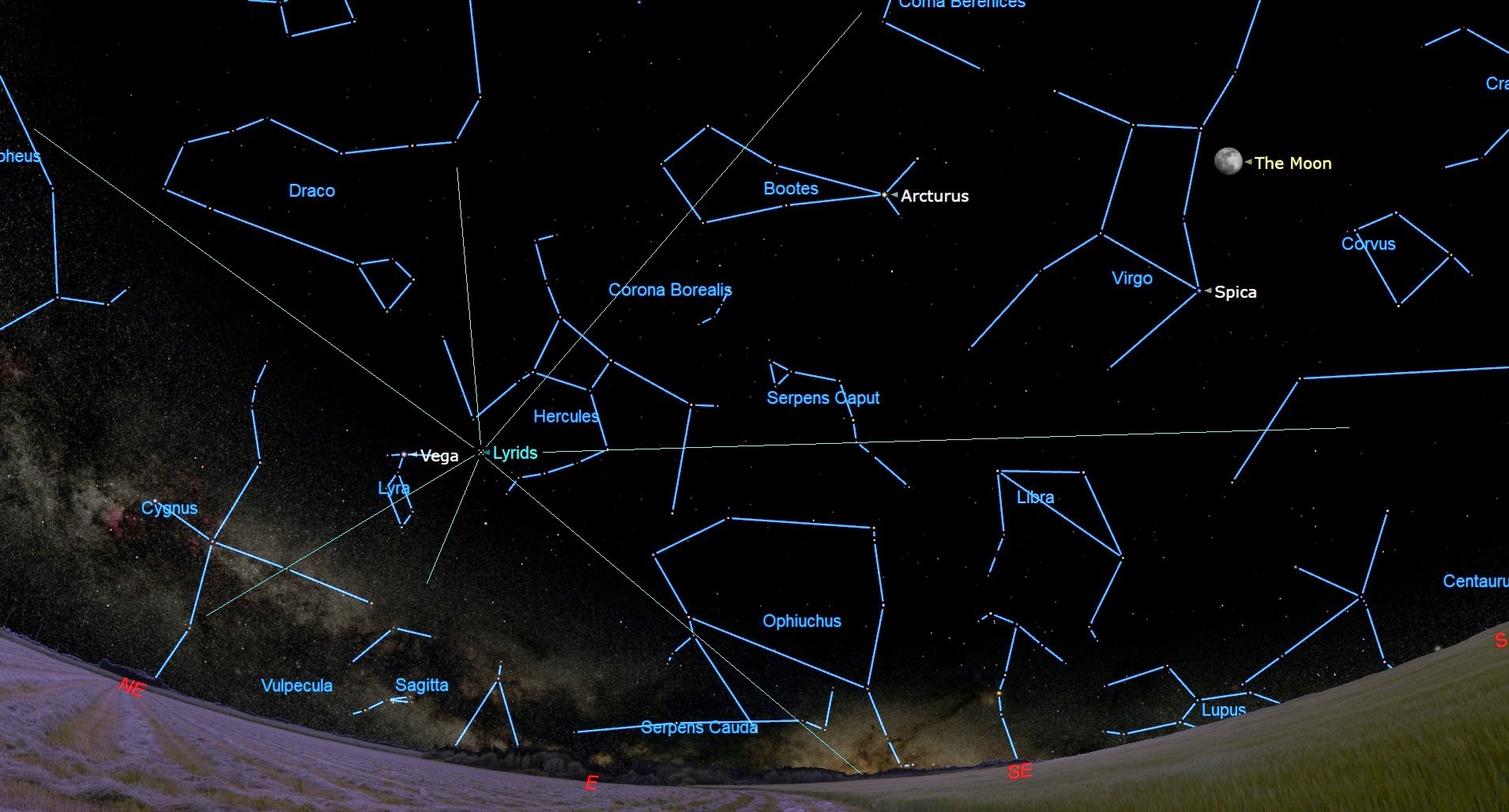

Located about 10-degrees to the west (right) of the bright bluish star Spica in the constellation of Virgo, the moon will be in the sky for much of the overnight hours of April 21-22, likely squelching a view of all but the brightest Lyrids.

Related: Lyrid meteor shower 2024: When, where & how to see it

Want to look at awesome stuff in the night sky? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

We also should stress that this is not a rich display, certainly not to be compared to the December Geminids or the Perseids of August. The number of meteors that might be seen by a single observer looking skyward under dark, clear skies normally is in the 10 to 20 per hour range.

But many of these meteors tend to be brilliant and appear to move fairly fast, streaking through Earth's atmosphere at an average velocity of 30 miles (48 km) per second. About a quarter of them leave persistent trains. Within a day on either side of the maximum, about 5 to 10 Lyrids can usually be seen each hour under good skies.

Related to Thacher's Comet

The Lyrids are actually the legacy of a long-departed comet bearing the name of Thatcher. This modestly bright comet was discovered in April 1861 by New York amateur astronomer, A.E. Thatcher.

The orbit of the Lyrids strongly resembles that of comet Thatcher which has an orbital period of about 415 years. They are cosmic rubbish; tiny bits and pieces shed by this comet on previous visits to the sun. The Earth's orbit nearly coincides with the comet around April 22 each year. When we pass that part of our orbit, we ram through the dusty debris left behind by the comet.

We call these meteors "Lyrids" because their paths, if extended backward, appear to diverge from a spot in the sky not too far to the south and west of the brilliant bluish-white star Vega, in the constellation of Lyra the Lyre, or Harp.

Vega does not begin to make its appearance until around 9 p.m. local daylight time when it rises above the northeast horizon. By 4 a.m. it climbs to a point high in the sky more than two-thirds up from the horizon to the point directly overhead.

Rather than risk a strained neck or shoulders we would recommend lying down on a long lounge chair where you can get a wide-open view of the sky. Bundle up too, for while it won't be a cold as on a winter's night, nights in April can still be quite chilly.

Read more: Here's how to see 'horned' comet 12P/Pons-Brooks at its brightest this week (video)

An oldie, but (sometimes) a goodie

Among all the meteor showers, the Lyrids are the oldest known, having been first recorded by the Chinese in 687 B.C. when "many stars flew from the northeast."

There have been other noteworthy Lyrid showers recorded such as in 15 B.C. (China), 1136 (Korea) and 1803 when many townspeople in Richmond, Virginia, were roused from their beds by a fire alarm and witnessed meteors that seemed to fall from every point in the heavens, resembling a shower of skyrockets. In 1922, an unexpected Lyrid rate of 96 was recorded, and in 1982 rates surprised observers by reaching 80 per hour.

So, the bottom line is that although the Lyrids are admittedly a weak display, they have also had a history to surprise observers, so it's always one to watch.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.