A collaboration between Texas Observer and MuckRock

In 2013, a wealthy tech executive donated a 50-acre parcel of land near a loblolly pine forest called the Lost Pines in Central Texas. Brooke Crowder, a self-described Christian sex trafficking abolitionist, promised to use it to “fulfill the call of my life.”

For Crowder, a mother of four and a Christian seminary graduate who had spent several frustrating years combating sex tourism in Costa Rica, her mission was clear: Amid the trees, she’d build a faith-based nonprofit that would become a nationwide model, the “Mayo Clinic of domestic minor sex trafficking,” as she described it.

When the Refuge for Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking—or, more simply, the Refuge Ranch—opened five years later in 2018, groups of teenagers ages 14 to 19 were sent to its sprawling campus, their stays oftentimes funded by private donors and both state and county grants. The young women it served, mostly from the juvenile justice or child welfare systems, had histories of sex work, often compelled by manipulative boyfriends or abusive family members.

By the end of 2018, largely through wealthy individuals, national Christian-affiliated nonprofits, and an influential Christian donor-advised fund, Crowder, the founder and CEO, had raised just shy of $10 million to run the Refuge Ranch and had a staff of more than 40, according to nonprofit tax filings.

Farmhouse-style cottages, each painted a crisp white with wood beams that frame patios, are clustered throughout the campus. A chapel serves as the centerpiece, casting a shadow on the two dozen buildings scattered below. They include cottages with separate bedrooms, a creative arts studio, rooms for yoga and movie screenings, a gym, on-site medical facilities, and even a boutique customized by the popular designer brand Kendra Scott, where the residents can pick out a new wardrobe as soon as they arrive. A chef has been brought in to teach cooking lessons and the Chicks, the country music band formerly known as the Dixie Chicks, spoke to residents over Zoom.

But for many girls and women here, the main attraction was the stable and pasture that sits next to the living quarters. Equine therapy was the Refuge’s major selling point and, upon entering the campus, residents tended to gravitate towards a horse they would call their own. Gideon, a brown stallion with a white kiss on his forehead, appears in promotional materials.

The program, trademarked as the “Refuge Circle of Care,” purported to be the first of its kind: a state-of-the-art recovery model with psychiatric services from the University of Texas’ Dell Medical School, classes and a degree program from the UT charter school system, and weekly therapy sessions. The women were supposed to graduate from the Refuge knowing “what love and nurture look like.” Since the Refuge opened its doors, dozens of young women have sought treatment here.

“Is this place real?” a former case manager, Zaneta Castro, remembers thinking when she first saw the Refuge. “It felt like a dream. I could not believe that something like this exists.”

But the Refuge wasn’t the sanctuary it was intended to be.

Problems at the Refuge Ranch first came to public attention in January 2022, when two female residents accused a nighttime monitor, Iesha Greene, of offering them Xanax and ecstasy in exchange for taking nude photos of themselves to sell online, court and inspection records show. The young women said they agreed, using Greene’s phone and a Cash App account to take the pictures and sell them. Greene was promptly fired, the incident was reported to authorities, and the Texas Rangers were asked to investigate.

About a month later, two young women ran away from the ranch. One resident who was found and returned to the facility alleged that multiple employees had helped her escape; the other was found by the Austin Police Department at a bus stop 10 days later. Two employees ended up leaving over the incident, and one was arrested for lying to the police during the investigation, according to a letter from the Texas Department of Public Safety.

In response to alleged misconduct by multiple staff members, in March 2022 the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) issued an emergency suspension of the program’s permit to operate. All residents were pulled out, and most were placed in other child welfare programs.

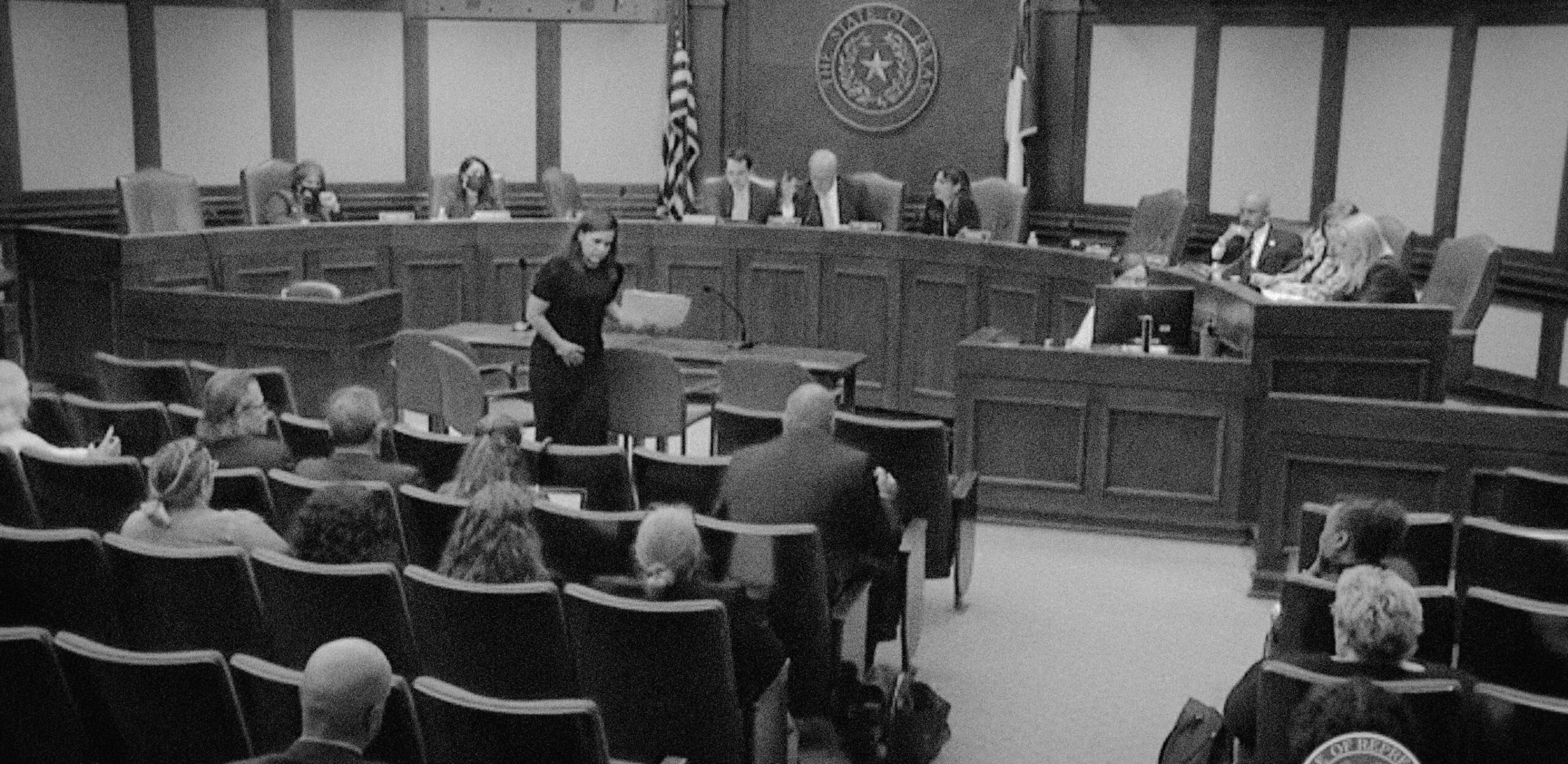

While the Refuge was on suspension, it was probed by multiple agencies. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick convened a Senate Special Committee on Child Protective Services to discuss the incidents along with other issues in the child welfare system. Monitors appointed by U.S. District Judge Janis Jack to audit Texas’ child welfare system published scathing reports about the Refuge.

In April 2022, the Texas Rangers began working with the FBI to investigate allegations of sexual exploitation at the Refuge. The investigation found no evidence of abuse. At the request of the Bastrop County district attorney, the Rangers presented findings to a grand jury, which declined to indict Greene or anyone else.

Greene, in an interview, denied the allegations lodged against her, calling them “lies.”

In January 2023, about 10 months after it was forced to close, the Refuge reached a settlement with HHSC that allowed it to reopen on probation. The conditions included implementing a reopening plan, monthly team meetings to evaluate the program’s compliance and efficacy, and a more robust screening and selection process for new hires.

In a statement on the Refuge’s blog, Crowder wrote that the “false allegations” had nearly bankrupted the nonprofit and vowed to reopen—and stay open. “We intend to emphasize the lessons learned from the process, work cooperatively with our state agency partners, and keep our eyes trained on the future,” she wrote in an entry that was later deleted.

While the Refuge was able to get its license restored, records from HHSC show the program was cited for more than 50 violations between 2018 and 2022, more than a dozen of which were incidents categorized as “highly concerning.”

What’s more, the Refuge apparently failed to report other incidents that are described in reports obtained through public records requests or in interviews with former employees.

In an email, Crowder told the Texas Observer and MuckRock that the Refuge has “reported every incident required by our regulators.” While she declined an opportunity to respond to each allegation in this piece—devoting her “time to the girls in our care” instead—she said that the accusations contain “grossly inaccurate information” that stem mostly from “disgruntled former employees,” and have been “utterly disproven during investigations by seven different agencies.”

Crowder also said she has “cards and letters of support” from the families of former residents in her files to counter critics.

The myriad issues at the Refuge Ranch raise larger questions about the quality of the state’s efforts to serve sex trafficking victims through residential treatment. Several costly residential treatment programs, the Refuge included, have left survivors with inadequate care and more traumatic experiences than they came in with, the survivors say. The saga of the Refuge is an example of one of the ambitious efforts in this niche world of advocacy that have faltered or failed in Texas, including others led by faith-based idealists.

What follows is the story of life behind closed doors at the Refuge, told through law enforcement records, state audits, tax and internal documents, text messages, and dozens of interviews with former employees, family members, social workers, and activists fighting to end sex trafficking in Texas.

Madelynn Bennetsen was only 15 when she arrived at the Refuge Ranch the week before Christmas 2019. She had been on the run with her trafficker, a man she called her boyfriend, who would eventually sell her to other men. When Bennetsen went missing, her mother, Nikki Bowie, tracked her location through a shared iCloud account. Bowie gave the location to police, who recovered her daughter by waiting undercover in a car outside the house she was in.

Bowie had heard of the Refuge Ranch and was hopeful that the program could help her daughter. But the cost without a government subsidy or scholarship was high, running into the tens of thousands for a monthslong stay. So Bowie pushed for a contract with Galveston County to help cover her daughter’s costs at the Refuge, which it did. For a while, the Refuge indeed helped her daughter.

“Mady was happy there for the first portion of her stay,” Bowie said. “She really started blossoming. She started a running club and got all the girls to do a big 5K. She ran through the finish line and then she would run back to run with the girls to encourage them.”

But after Bennetsen failed a drug test less than two months into her stay at the Refuge, staff members accused her relatives, who often visited, of sneaking her marijuana, her mother said. The accusation infuriated Bowie, who said she was told a Refuge staff member had passed her daughter a marijuana pen. While that staff member was fired, the incident does not appear in reports made to state authorities in that period that were obtained via a records request. Reporting it would have been required. After another resident assaulted Bennetsen in February 2020, her probation officer pulled her out of the program.

In retrospect, Galveston County officials called their contract with the Refuge a mistake.

“You go into this and you are trying to help kids with a history of sex trafficking, and you have this facility that is sparkling clean and brand new and well-funded,” said Glen Watson of Galveston County’s Department of Juvenile Justice. “You are trying to place a kid who has been through a lot at a place that looks like a five-star resort, but we started seeing issues. What we were trying to do wasn’t helpful. You try to do the best you can for kids, but when you find out it wasn’t the best, you gotta change course.”

Bennetsen then bounced around from a rehab facility, her parents’ house, and her grandparents’ house before ending up back in the arms of her traffickers. Her body was found hanging from a twisted bedsheet tied to a fire sprinkler in a Red Roof Inn in the summer of 2020. Her autopsy rules her death a suicide, and the Houston Police Department has closed her case.

Bowie feels like the system failed her daughter and struggles to understand the motives of the Refuge’s leadership.

“I don’t think they’re doing it for the right intentions,” Bowie said in an interview. “I just hope and pray that everything works out for them.”

Residential treatment centers have long been a model for housing certain children with emotional or behavioral problems. But centers specifically for young survivors of trafficking have only recently cropped up as public awareness about sexual trauma grew.

I don’t think they’re doing it for the right intentions. I just hope and pray that everything works out for them.

The Refuge is not the only Texas program for victims of sex trafficking that has struggled. Of eight child welfare programs in Texas designed to care for trafficked youth, four have recently closed their doors, at least temporarily: The Refuge, Hope Rising, Freedom Place, and Nicole’s Place. While poor performance noted in periodic inspections may lead a program to be placed on what they call “heightened monitoring,” Hope Rising, Freedom Place and Nicole’s Place decided to close on their own.

“Sex trafficking” is an umbrella term that describes a broad range of experiences, which complicates efforts to help victims. It can involve violent criminal rings that kidnap and exploit victims, holding them against their will and forcing them to sell themselves. But for minors, any form of sex for commercial gain is considered sex trafficking, including selling nude photos or pornography. Some advocates have switched from the term “sex trafficking” to “commercial sexual exploitation” or, more broadly, “trading sex.”

Those who work with young trafficking survivors say that victims often don’t recognize themselves as victims. Because traffickers tend to double as boyfriends—sometimes first loves, even—exploitative behavior can go unrecognized. Most young residents of these programs don’t want to be there, at least at first, making it harder for recovery efforts to succeed. The faith-based approach, common in the Texas foster care system, can turn off those it is intended to help and may be less effective than evidence-based secular treatment, activists and critics say.

The scale and cost of sex trafficking are difficult to quantify, but a 2017 University of Texas at Austin study estimated about 79,000 minor survivors of domestic sex trafficking live in Texas, costing the state $6.6 billion in social services throughout their lifetimes.

Six out of the eight Texas foster care programs for victims of trafficking have incorporated a belief in God as part of their treatment. Some organizations discriminate, hiring only self-avowed Christians (which faith-based organizations can legally do) while excluding LGBTQ+ applicants regardless of qualifications; others refuse to treat queer victims altogether. Several boosters of faith-based programs, like Crowder, dub themselves “Christian abolitionists” and paint the campaign against sex trafficking as the 21st-century equivalent of the movement to abolish slavery.

The U.S. government’s current anti-trafficking efforts are relatively new. In 2000, Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, the first federal legislation designed to protect trafficking survivors under the administration of former President George W. Bush. In 2009, Texas followed suit and launched the Human Trafficking Prevention Task Force, based in the Attorney General’s Office. In 2016, the Office of the Governor launched its Child Sex Trafficking Team. Along the way, cities and counties have inaugurated other efforts to prosecute traffickers and support victims. Nongovernmental organizations have hopped on board with awareness campaigns and rehabilitation centers.

Like many other anti-trafficking advocates in Texas, the Refuge’s founder, Brooke Crowder, is well-meaning and well-connected, former employees and other activists say. For this story, Crowder took a reporter on a tour of the ranch and answered some questions about its operations.

Crowder has dark auburn hair and wears dark lipstick to match, along with a diamond cross necklace. She is soft-spoken but becomes quickly impassioned when describing the Refuge’s mission. Besides her home in Bastrop, she and her husband, an executive in the electric utility industry, own a home in Telluride, Colorado.

In a 2018 interview for All Things Faithful, a Christian website, Crowder described her passion for anti-trafficking work, saying that it started while she was a student at Asbury Theological Seminary in Kentucky. One day at chapel, Crowder was shown a video of little girls being rescued from a brothel. At the time, one of Crowder’s four children was 6 years old, the same age as one of the victims.

“I sat in the pew, stuck there weeping until the place cleared out,” Crowder told All Things Faithful. “An hour later, my advisor found me, sat down next to me, and he said, ‘Brooke, I just want you to look around. There’s nobody else here weeping like this. I think this is the calling of your life.’ It was a prophetic word that I knew immediately was true.”

Crowder began researching sex trafficking. After graduating, she moved to Costa Rica with her husband and children to study Spanish. She spent four years trying to combat trafficking there by working with young women who were exploited by the sex tourism industry, but felt unable to make a significant impact. In interviews with other media outlets, Crowder said she felt she could make more progress with a network of supporters and funding. Her family landed in Austin in 2010.

“I didn’t know why we were coming to Austin,” Crowder told All Things Faithful. “Frankly, looking back, it seems that’s where the Lord was leading us.”

Crowder founded the Refuge just as sex trafficking became a popular cause among wealthy socialites across Texas. In 2017, a woman named Lisa Knapp organized a fundraising luncheon with 20 of her friends for the Refuge. The group of women raised $165,000 for the Refuge’s first residential cottage.

Members of that group, the “Austin 20,” are pictured in a group photo on its website in all-black outfits, staggered atop a flight of stairs leading up to a limestone building. The group has nascent plans to build another sex trafficking residential home in Williamson County, and inspired an offshoot—the “Houston 20.”

While the group began to support various anti-sex trafficking efforts, the Austin 20 collected enough to open its own treatment center, Nicole’s Place, in 2021. The organization raised $1.23 million that year, thanks mostly to an event called “An Evening with Larry Gatlin,” the Southern gospel country music star.

Nicole’s Place temporarily closed in March 2022 after operating for only a year. Knapp told the Austin TV station KXAN that the closure was due to a technical zoning issue—a cottage was located just 200 feet from where it needed to be.

Nicole’s Place has now reopened, but records show it has struggled to comply with state regulations. A footnote in a report from the court-appointed monitors tasked with keeping an eye on the Texas foster care system shows that Nicole’s Place had violated several of the state’s minimum standards. The report references egregious management failures, including citations for “failing to provide therapy for children for at least a month after the therapist quit” and inadequate supervision that “allowed a child to gain access to the internet, meet someone, and run away with that person.”

Even though the Refuge Ranch was designed to treat up to 48 girls at a time, no more than a dozen typically live there. The young women would begin their stay in a highly-supervised cottage, with a “house mom,” but as they progressed on personal benchmarks and earned trust with staff, they would level up to cottages with more freedom and responsibilities. It varied, but the average resident stayed about six months. While every day at the ranch was different, most were filled with school, recreational activities, therapy, and church on Sundays.

The vast majority of the Refuge’s budget comes from contributions, largely thanks to fundraising efforts, including a floral design competition at the Four Seasons Hotel and a culinary competition between master chefs at the ritzy Hotel Van Zandt in downtown Austin.

Since 2013, the Refuge has raised at least $22.6 million, according to nonprofit tax filings. Its largest donors include the Perry Family Foundation, run by the CEO of Perry Homes of Houston, and the National Christian Charitable Foundation, along with the philanthropic arms of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. The Refuge earned comparatively little from government agencies that sent teenagers to the ranch— $3 million between 2018 and 2021. During the pandemic, the Refuge Ranch also received a $665,000 federal Paycheck Protection Program loan and created a $200,000 endowment fund.

Crowder brought home a $53,000 annual salary in 2021, the most recent year of the organization’s tax forms, a major pay cut from what she made from 2017 to 2019, when she took home more than $100,000 a year. In 2021, two other directors were paid six-figure salaries. Direct care staff members, some of whom lived on campus several days a week, made much less, with starting salaries in the $30,000 range.

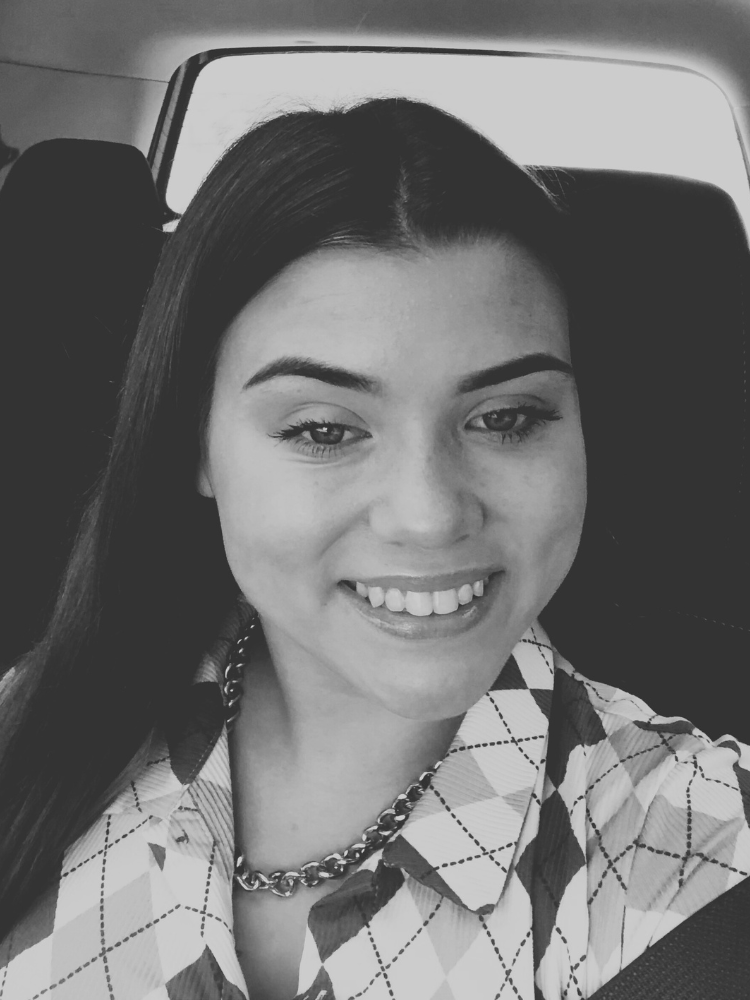

When Zaneta Castro became a Refuge case manager in 2018, she had a background as an investigator with Child Protective Services, though her most recent job was at a law firm. Castro was determined to make a difference in Texas’ child welfare system, and the resources the organization seemed to have at its fingertips felt unprecedented.

“The Refuge did not give me a book on how to be a social worker there. They basically were just like, ‘You’re experienced; you’ve done this, so help us put it together.’”

But Castro was surprised how quickly she was thrown into the mix with little orientation or training.

“The Refuge did not give me a book on how to be a social worker there,” she said. “They basically were just like, ‘You’re experienced; you’ve done this, so help us put it together.’”

For two-and-a-half years, Castro served as the Refuge’s only case worker. Getting a handful of teenagers wrestling with severe trauma to cohabitate in the middle of a forest was tough. Some days, the young women would get along great. On others, they became each other’s enemies.

Feeling unsafe exacerbated conflict at the Refuge, Castro said—some had felt safer with their traffickers than they did at the ranch. Over time, Castro grew increasingly frustrated with the lack of boundaries some colleagues had with the young women. Castro said some staff would allow the women to contact men and boys on staff cell phones and snuck them cigarettes, which wasn’t helping their progress.

By the time Castro left in early 2022, just before the Refuge got into trouble with the state, she already feared it wasn’t going to last. There was too much turnover and rules were too loose.

“I remember telling [management], ‘Something is not right. There’s something going on,’” Castro said.

Elizabeth Rogers was working on a master’s degree when she was hired as a “connection specialist,” to work directly with Refuge residents in September 2020. Rogers said she was the most qualified person in the group of new direct-care staff members. Most of the people hired in that group lacked any background in treating complex trauma, she said; one staffer’s only previous job was tending bar.

Since most of the residents are high-school-aged, the program includes education. While the UT charter school system provided teachers and curricula, Rogers worried the girls learned little. Now, when she communicates with former residents, she sees some can’t put together a coherent email.

Rogers also fears many participants left the program without understanding what sex trafficking was or that they are victims of exploitation. There was no education aimed at helping them understand what happened to them, Rogers said.

“A lot of them would be like, ‘Oh, well, I was just a stripper,’” Rogers said. “And I was like, ‘Did you keep any of the money that you were earning?’” When the victim would answer “no,” Rogers explained, “That’s trafficking, and you’re also 15.”

In her short time, Rogers said she “pushed really hard for a big change in the program, because it [was] not working, plain and simple. … They can’t tell me what [trafficking] is. Where’s the education on this?”

Under state standards, treatment centers are supposed to have phone lines that residents can use to contact people, including a hotline to higher-ups in the child welfare system to report situations that make them uncomfortable. While this phone line was recorded for the residents’ safety, Rogers said that sometimes, when girls would make reports against the Refuge, the calls could be used against them.

The director [would] beg girls not to make reports to licensing because, quote, they didn’t want to get in trouble.

“The director [would] beg girls not to make reports to licensing because, quote, they didn’t want to get in trouble,” Rogers said. The hotline was “monitored, and [leadership] would re-listen to calls and then ask the girls why they reported things.”

The director would sometimes offer treats or special privileges if residents promised not to complain.

“It could be as small as, ‘I’ll give you a Dr. Pepper.’ Or it would be, ‘I’ll take you on an outing to Dairy Queen tomorrow if you don’t record [the complaint],” Rogers said.

Breaking rules in exchange for favors was exactly the type of behavior that the Refuge was tasked with helping its teenage residents unlearn. Sex traffickers often offer gifts or treats to manipulate or coerce young women seeking love and approval.

The director declined a request for comment.

Melody Garcia served as residential director at the Refuge from 2018 to 2020 and later became the program’s compliance and training director. As good as the idea of the Refuge sounded, Garcia described the model as flawed. She also blamed bad hiring practices and the program’s faith-based mission for its failures. Garcia said she was laid off in November 2021 right as she planned to return from maternity leave—a move she attributed to making too many complaints about the organization’s management.

Because the Refuge is a registered faith-based organization, it is allowed to give hiring preferences to Christians. In fact, mentioning devotion to Jesus was key to getting a job, former employees say, even if other applicants had more experience or better qualifications. Even before she started at the Refuge, Garcia had heard that mentioning the magic words—“God,” “Jesus,” or “faith”—would make you a shoo-in. But hiring discrimination was even more overt than this, former employees said.

“I was told by the executive director at the time that gay people’s lives were a mess and that they didn’t deserve the privilege of working with these youths.”

“There was a specific, unequivocal directive that we were not to hire people who were gay,” Garcia said. “I was told by the executive director at the time that gay people’s lives were a mess and that they didn’t deserve the privilege of working with these youths. … To hear someone say that they didn’t deserve a job just because of their sexual orientation really broke me.”

In response, Crowder said that the Refuge works “to maintain an employment environment that is richly diverse and inclusive, representative of the population we serve.”

Some employees foisted their religious beliefs on residents. In one case, a staff member questioned the clothing worn by a resident, who was experimenting with their gender identity, for not being feminine enough, Garcia said. In another, the Refuge’s leadership was surprised and disappointed when they were told that they needed to provide religious accommodations for a resident who was a Jehovah’s Witness, Garcia said.

In a promotional video on the Refuge’s website, one of its board members, John Clark, a Houston businessman who also founded the anti-trafficking advocacy organization Operation Texas Shield, acknowledged that the ranch’s staff and volunteers “share our common faith as followers of Christ.” But Clark said that church and Bible study were not required, the Refuge Ranch had a non-discrimination policy and that staffers “do not force their beliefs on any of the girls.”

Residential treatment centers like the Refuge are not lockdown facilities—professionals in this field know that running away can be unavoidable. Rather than trying to prevent it at all costs, the more common approach is to “plant seeds” of safety and security in the young women so that, with time, they feel less inclined to flee.

Refuge residents often ran away—so much so that at one point, staff members implemented a policy that if the girls damaged the alarm system so they could run without setting it off, the cost of fixing it would be deducted from their chore money.

When Garcia was compliance director, the program director tried to implement a policy to take away runaway residents’ shoes, Garcia said. She pushed back, arguing that it would only make running away more dangerous given that the Refuge’s terrain has snakes, insects, and thorny plants.

Public records requests to HHSC showed nine documented instances of women running away from the Refuge between 2018 to 2022, but that appears to be a significant undercount. Documents the Observer and MuckRock obtained through a public records request to the Bastrop County Sheriff’s Office show approximately 30 reports of runaways between September 2021 and July 2023, despite the fact that the Refuge was closed for at least 10 months during that period. In response, Crowder said that all runaways were properly reported to authorities.

In August 2021, 17-year-old Shawna Rogers was released from the Refuge for an overnight stay with her grandmother. It was early for an overnight trip, Castro said—residents usually had to be at the Refuge for five or six months before leaving the premises overnight with family, but Shawna was granted leave after only three. She was staying at a motel in Bastrop and ran away when her grandmother fell asleep, taking her phone off the nightstand before hitting the road.

As Castro tells it, Shawna had told her friends at the Refuge that she planned to run away, and those girls relayed her scheme to staff members, who failed to report it to management.

Shawna had previously logged into Instagram on a staff member’s phone, which enabled Castro to access her account and send an investigator screenshots of her direct messages. They showed Shawna had been in contact with her trafficker and had plans to meet up.

In October, Castro got a call from another former resident, who was in a panic. She had met up with Shawna, and the two of them had gotten involved in a hit-and-run accident.

Shawna was in the hospital for a week on life support before dying of her injuries in October 2021, two months after she fled the Refuge.

Ultimately, the Refuge’s license was suspended in March 2022 while authorities investigated two issues, documents show.

One was that multiple Refuge employees helped two residents run away from the facility. The other, more publicized incident was that two residents accused a staff member, Iesha Greene, of coercing them to sell nude photos in exchange for drugs.

Because Greene had never previously been arrested, she passed the Refuge’s bare-bones background check. But if Refuge officials had checked references and contacted Greene’s former employers, they would have learned that she had previously been fired from a juvenile detention center for allowing residents to use her phone, accessing pornography on staff computers, and being flirtatious with one youth in her care, according to her personnel file and a lawsuit filed by one of the Refuge’s former residents identified as M.M. The lawsuit, which remains pending in the Bastrop County District Court, alleges that the Refuge failed to ensure the safety of a minor by failing to have appropriate policies and procedures, causing her “severe [psychological] injuries” and “mental anguish.”

This is a girl who has had a really rough life. Nobody has protected her, from her parents to her foster parents, to the Refuge.

“This is a girl who has had a really rough life. Nobody has protected her, from her parents to her foster parents, to the Refuge,” the victim’s attorney, Meghan Mitchell, said about her client. Her time at the Refuge “aggravated all of the issues she was supposed to get help for. They just made everything worse.”

In their response to the lawsuit, the Refuge denied all the allegations M.M. made against them.

Greene is not named in the lawsuit and was not criminally charged. In a phone interview, Greene said law enforcement agencies found “no evidence—not even one [thing]—and I know I didn’t do it.” (She also said that she quit before being fired from her previous job.) The fallout from the accusations, she said, was life-altering: Greene said she lost jobs; became homeless; was hospitalized and treated for depression; and her family, including her high school-aged daughter, “still has to deal with it.” “I’m trying to get my life back together,” she said.

The Refuge issued public statements about the incidents in the winter of 2022, saying it was “outraged by the actions of former employees whose intent was to harm, not help.” The Refuge has also denied all of the allegations, calling them “completely disproven.”

“We tolerated being dragged through the mud by opportunists from every quarter because we wanted one thing: the restoration of our license,” Crowder wrote in a related email.

In September 2023, the Refuge announced that it would be voluntarily giving up its license, citing an “intractable regulatory climate and pattern of hostility rather than collaboration from Texas’ Department of Family Protective Services (DFPS).” The state agency, Crowder said, had publicly revealed the location of the ranch, and the facility had been “the target of stalking and harassing activity from dangerous people, including criminal networks, who had trafficked the girls before.” In response, the Refuge hired armed security, which DFPS required it to remove, threatening stiff penalties or the loss of its license. So Crowder decided to close instead. (A spokesperson said HHSC did not find any evidence that the agency leaked The Refuge’s address to the public.)

“This only makes clear a tragic truth: the Refuge is the right model. Texas is the wrong state,” she wrote in the email to supporters on September 13.

A month later, Crowder announced that she would reopen since Texas officials had granted the program a special variance that will allow armed security on campus, which is strictly prohibited at other programs of its kind.

Crowder credited her donors for the state’s change of heart. “In addition to your calls, letters and even contributions, you also advocated for us in a way that has spurred a groundswell of action from our state regulators,” Crowder wrote in another email. On October 13, the Refuge held a celebratory luncheon with more than 130 supporters. The event was called “Hope Wins.”

While the Refuge has reopened, the property remains quiet. After all of the allegations, DFPS has stopped sending girls there, giving the program far fewer residents than it once had. But that hasn’t stopped Crowder from pushing for more.

“There are so few places of hope and healing for these girls, especially because most organizations like ours have shut down,” she said during our visit to the ranch. “So it really has just motivated us. Because the community has built this place, we have a strong responsibility to keep fighting for it.”

Crowder always planned to use the Refuge as a model to build more treatment centers for young sex trafficking victims. Now, similar programs are in the works, including Safe Harbor in Ohio. The organization will be the next faith-based “place of hope and healing for child survivors of sex trafficking.” Its website is decorated with pictures of the Texas property alongside boasts about its success.

Crowder will sit on its board.

Albert Serna Jr., a fellow at the news site MuckRock, contributed to this report.

CORRECTION: This story has been corrected to remove a reference to Nicole’s Place closing due to permitting issues with Texas’ Health and Human Services Commission. Nicole’s Place never had a permit with the state agency and temporarily closed after a zoning dispute. They are currently in operation.