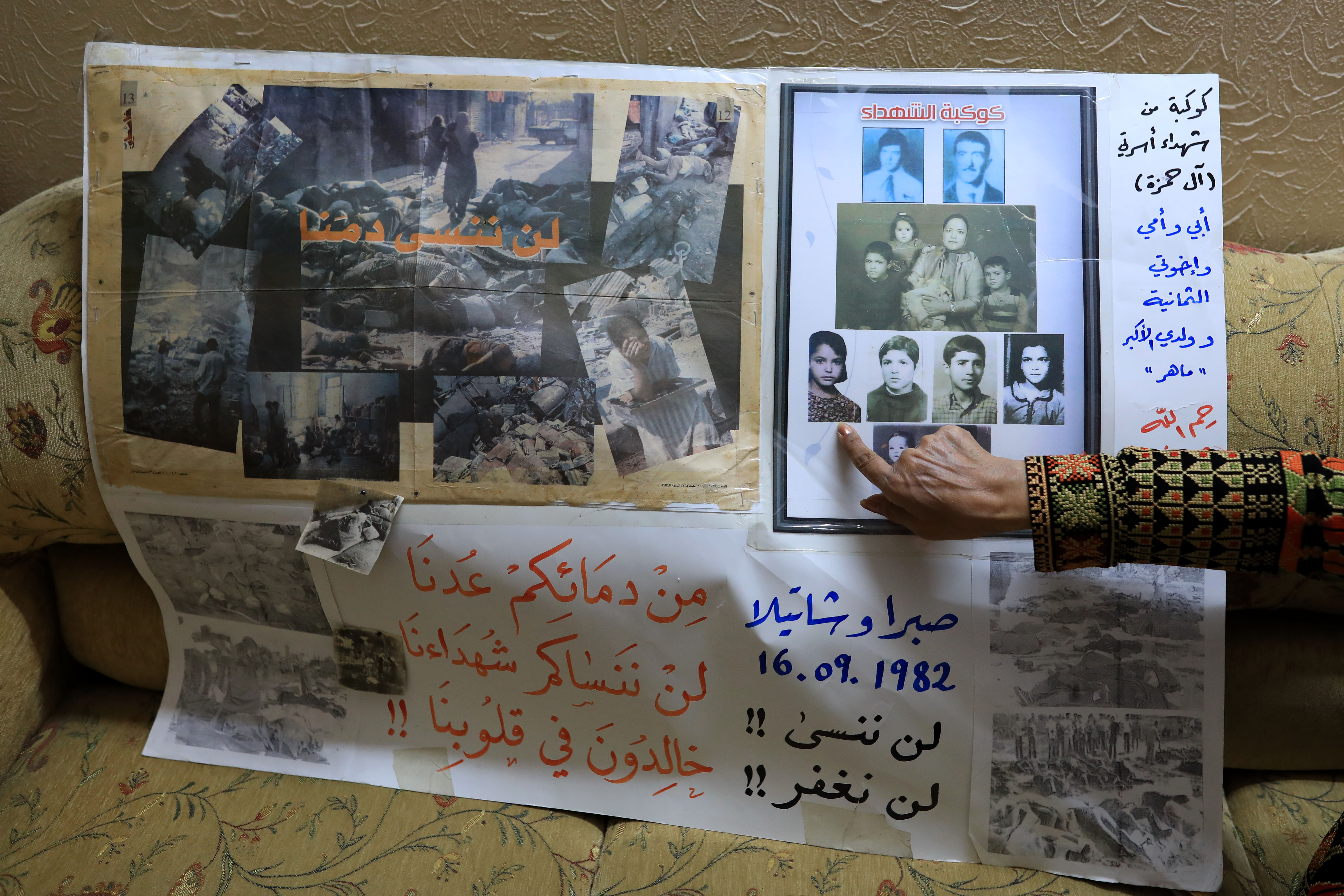

Beirut, Lebanon and the Gaza Strip – Every year on September 16, Rehab Kanaan lights candles in an open court in the centre of Gaza city, in memory of the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre, and her son and the other members of her family who were killed.

Kanaan was born in 1954 in Lebanon, where her family took refuge after fleeing the city of Safad during the 1948 Nakba, when hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were forced out of their homes after the establishment of Israel.

But Lebanon, and the Shatila refugee camp Kanaan eventually moved to, would not be a refuge.

In 1976, only a year into Lebanon’s devastating civil war, and six years before the infamous Sabra and Shatila massacre, Kanaan says that 51 members of her extended family were killed in the Tel al-Zaatar massacre, including her parents, her five brothers, and three sisters.

“It was a real tragedy. I was totally alone,” a tearful Kanaan said from her home in the blockaded Gaza Strip.

She tried to move on, but in her own words, “more tragedies awaited”.

By 1982 Kanaan had divorced her first husband, who she had two children with, and remarried, but remained in Shatila.

On September 16 of that year, after hearing about attacks by “Lebanese gangs”, Kanaan left the camp with her husband. Her children, 12-year-old Maher and 15-year-old Maymana, stayed behind with their father.

From September 16-18 1982, between 2,000 and 3,500 people were killed in Beirut’s Sabra neighbourhood and the adjacent Shatila.

The victims were predominantly the Palestinian refugees who lived in the camp, as well as Lebanese civilians.

The perpetrators: a right-wing Lebanese militia operating in coordination with the Israeli army.

Images from the aftermath were broadcast around the world, and the massacre is considered one of the most traumatic events in Palestinian history, with commemorative events held every year.

“After the massacre ended, I immediately returned to Sabra and Shatila,” Kanaan said. “It was a huge shock – body parts, blood and the dead, the scene was catastrophic. Many of my relatives and neighbours were killed, but there was no news about my children.”

“There was no one to ask, the situation was difficult, many people were killed, and everyone was looking for missing and dead people. This situation continued on for months.”

Along with thousands of other Palestinians, Kanaan left with her husband to Tunisia at the end of 1982, still uncertain whether her children were dead or alive.

“One morning, when I was in Tunisia, the Palestinian newspaper al-Thawra published a list of the martyrs who were killed in Sabra and Shatila – my son Maher’s name was among them,” she recounted.

“It was a very difficult moment. I was screaming hysterically, ‘Maher, Maher.’ It was very difficult news.”

As for Maymana, the trail went cold.

‘Smell of death’

Nawal Abu Rudeinah was six when the militiamen came to Shatila. Unlike Kanaan, she was not able to flee from the massacre, and neither were her family.

“I remember the strong smell of death. I remember walking between many dead bodies. It was unreal,” Abu Rudeinah, now 46, told Al Jazeera from her home in Shatila.

She explains that her father, Shawkat, and pregnant sister, Amal, were killed during the massacre, along with her grandfather, aunt, and 12 other relatives.

“There were people without arms, there were brains on the floor, there were women with their legs open and were covered with a blanket,” she continued.

“When they went into our home, they took all the men outside, put them in a line and began hitting them with heavy tiles on their heads. I will never forget this scene.”

Abu Rudeinah’s mother died of a heart attack five years later, and she was forced to drop out of school to take care of her younger brother, Mohammad.

“My childhood was horrible. We often didn’t have food. We would get donations from people but we raised ourselves. I would stand on a chair and cook. By the time I was 16 I knew how to do everything,” she said.

The Sabra and Shatila massacre continues to highlight the plight of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon today, who now number 479,000, according to the United Nations.

About 45 percent of them live in the country’s 12 refugee camps, which suffer from overcrowding, poor housing conditions, unemployment, poverty and lack of access to basic services and legal aid.

Palestinians in Lebanon are banned from working in as many as 39 professions and owning property, and face numerous other restrictions.

“Life in the camp is very hard. I think if you ask everyone they all want to leave. We are still carrying the label ‘refugee’ and it’s been 74 years and we are still refugees,” said Abu Rudeinah, whose family were expelled from the city of Haifa in 1948.

“The Lebanese state does not want us either, ok fine, so let us go back to our homeland, imagine going back, to be surrounded by your countrymen. Our dream before we die is to visit the Al-Aqsa Mosque.”

Twenty-two years searching

The Lebanese restrictions on Palestinians that make life so difficult for Abu Rudeinah also meant that Kanaan could never return to look for her daughter Maymana.

Instead, she spent 22 years fruitlessly searching, asking after relatives and neighbours in Lebanon to try to reach her daughter.

Eventually, she managed to find one connection to her life in Lebanon. A number for a long-lost aunt.

“I gathered my strength and called. My cousin answered. I asked her one question: Is Maymana alive or not? She said yes, she is fine.”

“I began screaming for joy and crying.”

Two years later, in 2006, Kanaan met her daughter Maymana in person, when Abu Dhabi TV organised a meeting between the two live on television.

“It was a memorable day. I couldn’t believe my daughter had grown into such a beautiful young woman after I had left her as a little girl. I embraced her in a long hug that made everyone in the studio cry.”

Naturally, Kanaan wanted to make up for the lost time.

But the reality of her life in Gaza, which has been under a 15-year Israeli blockade, and her now-married daughter’s life in Lebanon, means that it has been difficult to meet.

“My life is a series of pain and suffering. I lost my family in one massacre, and lost my son and cousins in another massacre.

“Then, I tasted the bitterness of searching for my daughter for years, and I found her, but she is far from me. What more can Palestinian mothers bear?”

Maram Humaid reported from the Gaza Strip, Zena al-Tahhan from Jerusalem and Ayham Alsahli from Lebanon.