In a fridge at The Little Car Company’s factory at Bicester Heritage in Oxfordshire is a bottle of champagne. The idea is that anyone who drives a mile in one of the company’s bespoke electric classic cars and doesn’t return with a smile on their face wins the bubbles. To date, four years after the company was established, the bottle remains unopened.

The Little Car Company (TLCC) is the brainchild of Ben Hedley. Founded by 2019, its first project was the Bugatti Baby II, a meticulous recreation of the famous pre-war single-seat Type 35 Grand Prix car.

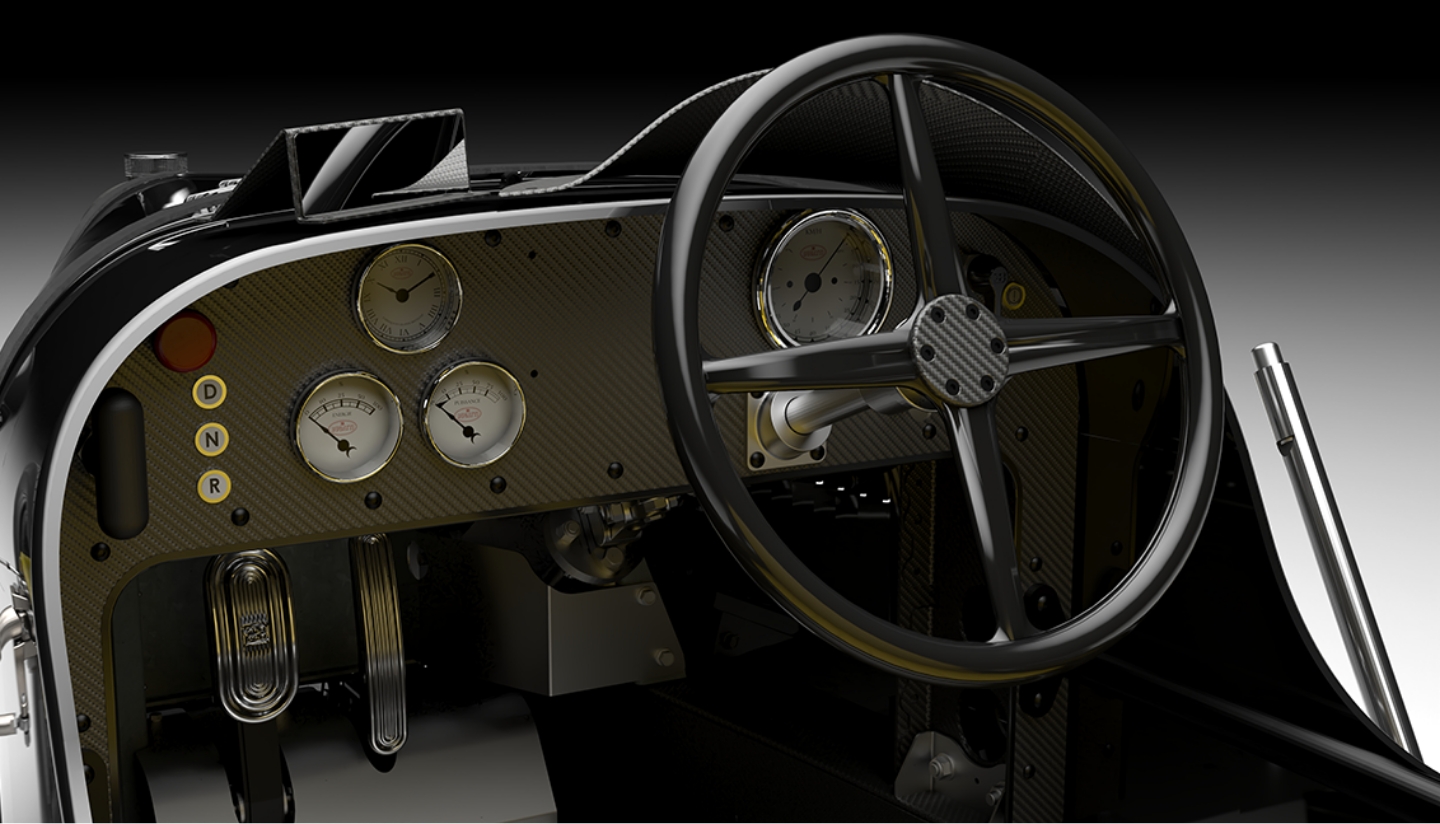

Built at 75 per cent scale, with exacting attention to detail, the prototype, Hedley proudly tells, was sent over to Bugatti's HQ at Molsheim in France for approval, where it received a rapturous reception. Hedley originally intended to create a modern update of Ettore Bugatti’s own Bugatti Baby, a driveable 50 per cent scale model built in 1926 for his son Jean that went into limited production for eager customers.

The Little Car Company and its electric dream machines

The original plan had been to create a precise half-scale replica, but Hedley and his team quickly realised that building a ‘junior classic car’ without considering its potential as a grown-up toy would be a missed opportunity. To that end, the Bugatti Baby II was designed from the outset to be as delightful to drive as the original, only this time with electric power at its heart.

‘I’ve come around to electrification in classic cars,’ Hedley admits, pointing out that ‘the originals are just too expensive to drive’. Examples of the Type 35 have reached prices of nearly £4m in recent years, thanks to its combination of provenance, brilliance and the eternally attractive Bugatti name. TLCC’s Baby II is true to Hedley’s assertion that ‘we don’t do replicas, we do reinterpretations’, with elements taken from Bugatti’s production cars, as well as limited editions built for owners of modern machines like the Mistral.

‘The brands have realised that they’re educating the next generation of customers,’ Hedley notes, with the second model in TLCC’s portfolio tapping directly into the cerebral cortex of Dinky toy owners who went on to acquire the real thing. The DB5 Junior, officially licensed by Aston Martin, is a very different beast to the stripped-down Bugatti. Plusher and more luxurious, it’s also much more complex, with 1,200 parts versus the Baby II’s 700. The braking system is by Brembo, taken from a Ducati bike, the dampers are by Bilstein, and the car was signed off by Darren Turner, one of Aston Martin’s experienced racing drivers and handling specialists.

It’s available in three versions, a ‘basic’ model, a high-performance Vantage model and the ultimate in cinematic collectables, the No Time To Die Edition. The last, which starts at £90,000, incorporates a genuine smoke screen, retractable headlight machine guns (not genuine), a revolving digital number plate and more. ‘I was a massive James Bond fan,’ Hedley admits. ‘It sounded like a brilliant idea, but it was actually next-level complexity.’ Just 125 will be made.

Finally, there’s the Testa Rossa J, an immaculately beautiful reconstruction of Ferrari’s legendary late 1950s racing car. Various versions of this classic machine were built, but TLCC have chosen the 1958 250 TR model, bodied by Scaglietti with its distinctive ‘pontoon fenders’. Keen competitors can specify the Pacco Gare model, which increases the power, and adds a roll hoop, spotlights and a tonneau cover. Like the DB5 and Baby II, every element is hand-assembled, with many suppliers drawn from the real world of classic car parts – wire wheels from Borrani, steering wheels from Nardi, instruments by Smiths and tyres from Pirelli.

‘Ferrari was the last brand on our radar,’ Hedley recalls. ‘I went to Milan to present three options, but they’d already chosen the Testa Rossa. Yes, they’re tough to work with, but once you’re through the door they’re brilliant.’ With a hand-formed aluminium body over a tubular frame, and genuine Ferrari badges on the nose, it’s about as authentic as it could possibly be.

Remember your racing goggles

We’re back to that bottle of champagne. Bicester Heritage is set within the grounds of a former RAF base and still has active runways. Handily, the extensive taxiways double up as a compact racetrack, so TLCC has plenty of space to show off what its little cars can do. The combination of scale, light weight and a zippy electric motor brings another crucial element to the package; all of these cars are enormously fun to drive. The Bugatti and Ferrari tip the scales at barely 250kg, with the DB5 slightly heavier at 350kg.

All models follow a similar approach, with an electric motor driven by a modular battery system. Want more power? Add another battery. In the Bugatti you sit low but exposed, sticking out of the upright cockpit like a true vintage racer. The small scale means that both DB5 and Testa Rossa offer a similar go-kart-style experience, albeit it’s slightly harder to squeeze down behind the wheel.

Once you’re there, the little cars of TLCC can be thrown around Bicester’s wide track with abandon. The power is instant, the steering razor sharp. All three cars can be made to slide satisfying around corners, with the squeal of rubber on tarmac the only sound you’ll hear. The Ferrari is a particularly exhilarating experience, with the Pacco Gare’s extra power helping the sleek little machine scythe through the air – racing goggles would have been a good idea. The champagne stays on ice.

The batteries provide enough juice for around an hour of tearing up the track – and slotting in a new one is a simple trackside operation. Hedley says plans are afoot for an endurance race event with teams of adults and children sharing the driving. About 90 per cent of TLCC’s cars are exported, with an optional bespoke packing crate serving as a storage garage once they’ve arrived. Many buyers already own the real thing and want their little version to exactly match the livery and trim of the original car. The company also offers a ‘flying doctor’ service for repairs and upgrades.

‘We build our cars to road car standards, but brands have asked us not to make them road legal,’ Hedley says, adding, ‘although clients have.’ TLCC fans might be interested in the company’s next projects. In a crashing tonal change, the other prototype in build (apart from a very secret project for another storied British manufacturer) is TLCC’s Tamiya Wild One MAX, an electric off-road buggy based not on a real car, but on a remote-control car made by the iconic Japanese modelmaker in the 1980s.

As a scaled-up model, the Wild One MAX is effectively ‘life-sized’, even though at 3.5m long it’s shorter than a Fiat 500, than with the added bonus of being road legal. The Wild One MAX has a top speed of around 60mph, as well as massive ground clearance for bashing dunes and an optional windscreen. It would take some grit, but you could certainly commute in this if you tried hard enough. Small electric cars now have a new kind of champion.

Bugatti Baby II, from £31,000, BugattiBaby.com

Aston Martin DB5 Junior, from £39,000, TheLittleCar.Co

Ferrari Testa Rossa J Pacco Gare, price on application, TestaRossaJ.com

Tamiya Wild One MAX, price tbc, WildOneMAX.com