Genius may be most familiar under arc lights and with an audience, but it is here, in a batting cage an hour past sunup on a quiet March morning in West Palm Beach, Fla., where it has its foundry. With beautiful violence and the same 75-swing legato, Juan Soto starts every baseball day since he became a professional at 16 years old.

There is no technology. No cameras. No Trackman. No accoutrements. It is just a bat, a bucket of baseballs, Nationals hitting coach Joe Dillon and, when it comes to master levels of power, patience and contact, the greatest hitting prodigy since Ted Williams.

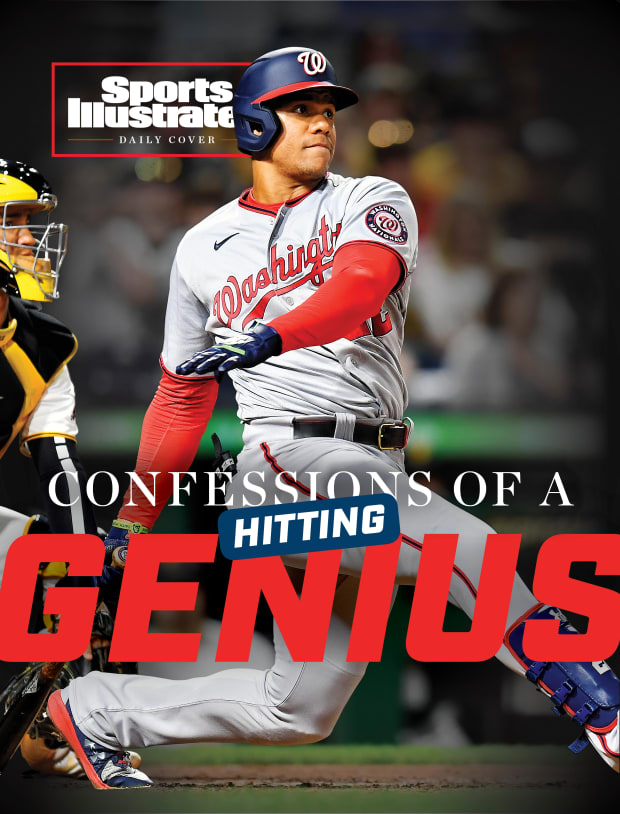

Joe Sargent/MLB Photos/Getty Images

Soto, the Nationals’ right fielder, is 23 years old, the same age Frédéric Chopin, another prodigy, was when he published his first set of Études in 1833.

An études is a batting drill for a pianist. It is a short work written as a teaching aid. But from the hand of Chopin, études elevate to concert repertory. So it is with the Études of Soto: Utilitarian practice becomes artistic masterwork.

Not once in his 75 swings off various types of flips from Dillon does Soto hit a ball off the top net. Most swings produce line drives toward left center, the favorite direction of his left-handed swing. In one sequence Soto doesn’t swing at the flips but knocks them straight down with the end of the bat knob.

“I never want my bat to get away from my head,” he explains. “I want to feel it real close to my body. This reminds me to be quick to the ball and always work a little bit down to the ball.”

The session ends with Dillon mixing the speed and location of the flips. From 15 feet away, Soto must decide whether the ball is a strike or not. He is never wrong with his swing decisions. He has been using the same training program since minor league hitting coaches Troy Gingrich and Jorge Mejia showed him on his first day at Instructional League camp in 2015. This session goes especially well.

“My bat,” he says, “is flying right now.”

What makes a hitting genius? The fundamentals of études, for one. Also, at 6’ 2”, 224 pounds, Soto is a physical marvel. With his strong glutes and thighs and wide stance, he is the Colossus of Rhodes in the batter’s box. Only an earthquake could topple him from his base. Such steadiness enhances his extraordinary vision. And if he decides to swing, Soto fires his powerful hips to unleash his quick, flat stroke.

There is another tool that makes Soto such an outlier: his mind. His ability to decode pitchers and the spin of a baseball is so unusual that Johnny DiPuglia, the Nationals scout who signed Soto, calls it “UFO stuff.”

Soto has played 464 regular-season games. At that juncture, only Williams also had 90 homers and 350 walks—and their totals (Soto has 98 and 373; Williams 99 and 375) are eerily close. As with Williams, Soto stands apart because of how well he sees the baseball and the game.

One afternoon after a spring training workout, Soto explains in detail how the genius of his hitting mind works. The stories are so amazing that when he is done, even Soto realizes they sound so preposterous that he needs to add something.

“I mean, people are going to think I’m lying through all this!” he says with a laugh. “They’re going to think it’s all lies. I hope they don’t. I don’t lie at all. It’s all true.”

Indeed, the legend of Soto is all true. How DiPuglia signed him out of a urine-soaked batting cage occupied by a homeless man. How one muddy day in Class A ball Soto, with his shuffle, turned the mundane of taking a pitch into a signature move. But especially how he conquers some of the best pitchers by seeing the game on a higher level.

“I don’t keep notes. It’s mostly in my head,” he says. “It can be a move, sometimes the way they throw a pitch, or the way they might miss with a pitch and go, Oh, that’s my fault. It can be any move they make that makes me go, That’s something.

“Justin Verlander. Game 6. World Series.”

And we are off. Confessions of a hit man begin.

Facing elimination and Verlander, the Nationals are tied with the Astros in the fifth inning of Game 6 of the 2019 World Series. Soto is at bat with two outs and the bases empty.

Verlander misses his spot high on three straight fastballs, the last one barely so. Soto fouls it straight back. Soto says to catcher Robinson Chirinos, “He throws that pitch a few inches lower, I’m hitting a home run.”

Verlander misses with another high heater, although it’s close enough to the upper inside corner of the zone that Verlander flinches in disgust when umpire Sam Holbrook calls it a ball. Soto notices Verlander’s pique as he shuffles his feet in his leonine, menacing manner. He sees something. Then he nods his head 13 times. And when Chirinos says something to him about the borderline nature of the call, Soto, with a smile on his face, replies, “Ball.”

Soto smiles not just because he was right about the pitch’s location. He smiles because he knows what is coming next.

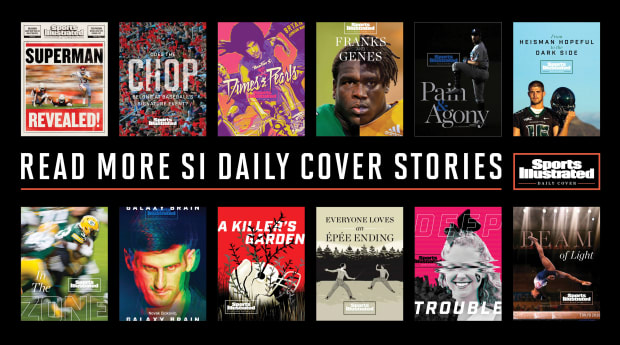

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

The antediluvian battle between pitcher and batter, in which one tries to keep the other from reaching base, is not a fair fight. Pitchers have won 65% to 69% of the time in every decade over the past hundred years. So sublime a hitter is Soto that he flips that century-old equilibrium. Soto seized the mathematical advantage over pitchers in the second half of last season. He won more than he lost. He became only the fourth player to post a .525 on-base percentage and hit 18 home runs in the second half of a season. The others: Babe Ruth, Williams and Barry Bonds.

“Do you know when you have a pitcher in trouble, when you’ve flipped the odds?” I ask him.

Soto says nothing. He smiles and nods mischievously.

“When does that happen?”

He smiles even more broadly.

“When you see the shuffle.”

The shuffle began, he says, to keep his spikes clean.

“I was in Low A,” he says. “It was a really bad day. It was raining and everything. All the mud was getting in the way. I just tried to clean it up and put my feet in the dirt and that’s when I started shuffling. Every pitch I took I just tried to clean it off, and pitchers started taking it personally. I was like, Are you taking this personally? Well, I’m going to keep doing it. If you get mad, I don’t care.

“Sometimes you try to find a way to get the pitcher out of his mind and try to get him out of his game. That’s when it started, and I kept doing it.”

He has since removed the crotch-grabbing part (“Yeah, I cleaned it up. I made it better.”), but the steely stare, the spread haunches and raised shoulders remain unmistakable kinesics. Soto is claiming territory. The territory is the approximately 3.3 square feet of the strike zone, and he is not going to be fooled into swinging at something outside that space. Last season nobody swung at fewer pitches out of the zone than Soto (12.2%).

“He is in total control of the at bat,” says former teammate Ryan Zimmerman. “These are the guys every sport needs—the five to 10 guys who are just so much better than everyone else. He’s one of those freaks.

“And actually, his success rate is a lot more than what you think. Other teams know they’re not going to let him beat them. He’s getting much more of a limited opportunity. It’s pretty ridiculous.”

In 2021, for instance, Soto ranked with Bryce Harper, Vladimir Guerrero Jr., Fernando Tatis Jr. and Shohei Ohtani among the top five OPS hitters in MLB. Soto did his damage with 911 swings. The other four averaged 1,152 swings, or 26% more.

Soto saw 2,601 pitches last year. It is the nature of such volume and the grind of a season, aches and pains, lousy weather and lopsided scores, that focus wanes, which results in “giving away” a plate appearance. To Soto, every one of those 2,601 pitches is the Battle of Agincourt.

“It doesn’t matter if we are losing 20–0 or winning 20–0,” Soto says. “I won’t give it away. Because at the end of the day, I don’t want them to say, ‘Oh, he hit .299 because he gave one at bat away when they were winning 20–0.’ They all count the same.”

The Nationals’ 2019 season is four outs away from expiration when Soto bats against Brewers relief ace Josh Hader in the wild-card game. Two outs. Bases loaded. Down 3–1.

“What do I tell myself? It won’t be a slider,” Soto says. “Because if you’re paying attention to the game, he was trying to throw his slider, and none of them were for strikes. So I removed the slider. I just sit on fastball all the way.

“I know he’s going to throw it and I know he’s going to throw it high because that’s his best pitch and I know it’s going to be hard. So I tell myself, Get on time. Get a single through the middle and then enjoy.”

Hader starts Soto with a 97-mph fastball. Soto fouls it back. The next pitch is a slider off the plate that Soto rejects with such impunity that he breaks out the shuffle, stares at Hader, tugs at his crotch, shrugs his shoulders like a boxer waiting for the bell and then, staring at the ground, cracks a fiendish smile. Uh-oh. Hader is in trouble. He has thrown 29 pitches. Only six were sliders. Only one of those was a strike.

Soto knows what’s coming. Batters are hitting .168 against Hader’s fastball. This one is 95.3 mph at the top of the zone. It is the slowest of the 24 fastballs Hader throws that inning.

He pulls it for a single into right field, where it takes an odd bounce past an overly aggressive Trent Grisham. All three runners score. The Nationals win, 4–3. Soto is only the third player—and the youngest ever—to turn a deficit into a win with a hit that late in a sudden-death playoff game, joining Francisco Cabrera of the 1992 Braves and Edgar Martinez of the ’95 Mariners.

Will Newton/Getty Images

Soto fell in love with baseball because of the Red Sox and their Dominican stars, Pedro Martínez, David Ortiz and Manny Ramírez. Young Juan would rip two sheets of paper from a notebook, crumple them into a ball, cover it with tape and act out by himself a Red Sox–Yankees game in a hallway of his house.

“I used to live in a tough hood [in Santo Domingo], and my mom didn’t let me go out that often so I had to find a way to have fun,” he says. “I used to throw the ball in the air and just hammer it up the middle and run around the bases, back and forth in the hallway. And I remember thinking that was everything.”

Soto was invited to play in Dominican Prospect League games at Fort Lauderdale Stadium in 2015. DiPuglia already had Soto on his radar.

“First at bat, he hits a line drive off the wall in left center,” DiPuglia says. “Second at bat, he takes a slider in and hits it off the wall in right center.”

DiPuglia left his seat and approached Soto’s manager. “Let me have him for a little while,” he said. DiPuglia brought him to a decrepit batting tunnel where years ago Yankees greats such as Dave Winfield and Don Mattingly hit when the site was the team’s spring training home.

“There was a homeless guy in there,” DiPuglia says. “I gave him 20 bucks to get out. It stunk like urine. It was nasty. It was the only way I could get him alone for my final report. We started doing flips, just to reinforce his barrel awareness and how he adjusts his hands to different parts of the zone.”

Hearing the loud sounds of contact, two scouts for the Diamondbacks scrambled to see who was swinging the bat. They arrived to see DiPuglia shaking hands with Soto and his agent, Cristian “Niche” Batista, on a $1.5 million bonus.

“He hit the ball foul pole to foul pole without trying to hit every ball out the way most kids do,” DiPuglia says. “His eyes are ridiculous. You could tell he had good eyes by the way the ball hit his barrel. A lot of guys, you pick up their bat and you see ball marks up and down the bat. This guy wore out the barrel. It was unbelievable.”

The story of Clayton Kershaw in Game 5 of the 2019 NLDS is so wild Soto must start with a disclaimer. “People are going to think I’m lying,” he says, “but definitely yes, I said to myself, I am going to hit a home run.”

The Dodgers are winning, 3–1, with two outs in the sixth inning of another sudden-death game for Washington. Enrique Hernández of Los Angeles pulls a curveball foul into the left field seats. After giving the ball a brief chase, Soto, playing left, peeks into the Dodgers’ bullpen behind him. He sees Kershaw warming up.

“That’s when the mind games start going,” Soto says. “I turned around to look at the bullpen, and Kershaw was looking at me. He stopped his windup halfway when he saw me. I don’t know if it was because he was trying to do something, but he stopped halfway. I saw that and I was like, He don’t want it. Well, I’ve got more confidence now.

“I start thinking, What has he been throwing you that he’s been getting you out on every time? Sliders down and away. So I was thinking I just have to get one up and hit it to left center to tie the game. I said, ‘[Anthony] Rendon is going to hit a double, and I am going to hit a homer to left center to tie the game.’ ”

He is wrong. Slightly. Rendon hits a low fastball for a homer. Kershaw, one of baseball’s best lefties, had thrown Soto 10 pitches in the series: eight sliders, one curveball and one fastball. Soto knows what is coming on the first pitch.

“I was like, Slider down and away. Hit it to left center,” he says. “He missed. It was right down the middle. You hang it, we bang it.”

Soto pulls the slider halfway up the pavilion in right field. Washington wins, 7–3.

“These are the stories I like to keep to myself because people might think I’m lying,” Soto says. “I don’t care. It’s the little things I see.”

John McDonnell/The Washington Post/Getty Images

Soto drew 145 walks last season at age 22. Only one hitter that young had such a keen eye: Williams, who walked 147 times at 22 in 1941, the year he hit .406.

Time is the currency of hitting. The sooner a hitter reads the pitch the more time he has to operate the radar defense system in his head: Identify the object, calculate its speed and trajectory and, if all adds up, smash it to smithereens. Soto’s vision buys him time. Sometimes he can read a pitch before it leaves the pitcher’s hand.

“I try to see the hand of the pitcher,” he says, then makes a circle with his thumb and index finger, the traditional changeup grip. “I can see this a lot while the ball is in his hand. Then you know, changeup. I can’t see the curveball grip, but every time I see it pop up out of the hand, I definitely can see that.

“I can’t tell if it’s a sinker or a cutter, but with the spin on the way [to the plate], you definitely know where the ball is going to land. With sliders, I can see the dot on the ball. Definitely. But not all of them have a dot. Most of them have just a big circle. You’ve got to see the fastball and the slider. Then I go, O.K., the fastball does this; the slider does that.”

The key to operating this decoding system is the steadiness of his base. Think of his eyes as a high-def camera and the legs as its stand. By remaining so still and balanced, Soto captures the baseball in remarkable clarity. Cameras that move blur the image.

“For your eyes to be good, this and this”—Soto taps his head and chest—“have to be good. You have to control your body. You have to have balance with your body to see the ball well. Because if your body is going too much forward, every ball [looks like] a fastball. Every one.”

On the eve of Game 1 of the 2019 World Series, hitting coach Kevin Long tells Soto, “Gerrit Cole is going to go upstairs with his fastball. You’re going to hit a home run off it.”

In the first inning Houston’s Cole strikes out Soto on three high fastballs at 97, 98 and 99 mph.

“I just tried to get a little more on time on the fastball and try to make contact,” Soto says. “He just went by me with three fastballs, so I was ready for it the next time.”

They meet again in the fourth inning. Cole throws a high fastball at 96 mph with his first pitch. Soto destroys it 417 feet to left field for a game-tying home run.

“That was perfect-perfect, like in the game The Show,” Soto says. “Perfect-perfect contact. That was loud. Yeah, that was loud.”

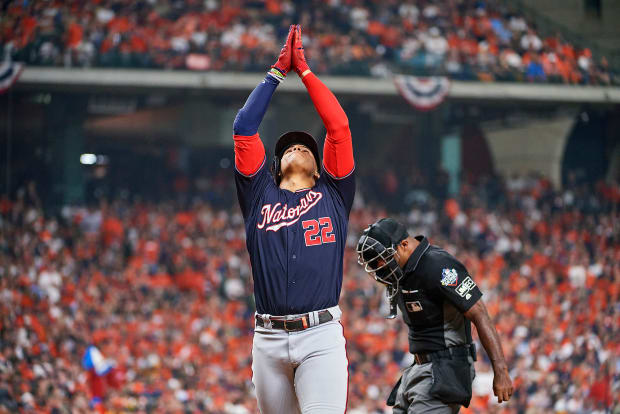

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

Ask Soto what he loves most about baseball, and his answer is of an aesthetic, not an accomplishment.

“To see the fade of the ball going to left field,” he says, smiling at the vision of it in his mind. “I really do love it. Every time I hit the ball to the 399 sign, I love to see the ball that way and the way it is spinning. I heard this from a lot of good hitters: Hitting is like a dance or an art. Every time you see the ball jumping off your bat you just feel amazing. When you see the way the ball is going and the way the ball tails, it’s crazy.

“It tells me my swing is right, and I’m inside the ball and I’m keeping it as tight as I can. Like Kevin Long used to tell me, ‘You keep it tight, you keep it right.’ ”

Verlander looks for the sign from Chirinos for the fifth pitch of the at bat, the first one after the Soto Shuffle. Soto knows what is coming.

“He was fighting with the umpire,” Soto says. “He wanted to throw that pitch the whole at bat. He kept missing.

“I knew he was going to throw me a fastball. It was because of a lot of things. It comes with the at bat before. He threw me a slider and I hit a double. So 3–1, his best pitch is the high fastball. His changeup is all right, and his slider is good, but he doesn’t want to walk me. The Astros don’t like to walk people. The bases are empty, so he’s going to challenge me with the pitch he wanted to throw the whole at bat.

“So I’m going to attack.”

Verlander throws a high fastball just inside the top of the strike zone. Soto had told Chirinos he would hit a home run if Verlander threw it a few inches lower than the one he fouled back. This fastball is 3 ½ inches lower, or a little more than the diameter of a baseball. Soto blasts it 413 feet, more than halfway up the second deck in right field at Minute Maid Park.

The home run gives the Nationals a lead they never lose. They win the World Series the next night with a 6–2 victory in which Soto becomes the youngest player to reach base three times in a World Series Game 7.

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

Verlander is told Soto knew what was coming based on the pitcher’s extremely brief physical reaction to Holbrook’s call on the 2-and-1 pitch.

“I did feel like it was a strike,” he says. “Borderline pitch. Big situation. I wanted it. Didn’t get it. I definitely don’t think I gave him anything.”

The MLB average launch angle is 12 degrees. Soto’s launch angle is less than half of that, 5.8 degrees, which ranks him 162nd of 176 hitters.

Verlander reconsiders what happened in the World Series. “Maybe he did see something,” he says. “Maybe there was something there. I don’t know what body language I’m giving you to send something. That’s why the best poker players in the world can pick up on tells.”

Chopin wrote more than 200 works for solo piano, but it was one of his Études, Op. 10, No. 3, that he considered the most beautiful melody he ever wrote.

“After one has played a vast quantity of notes and more notes,” he once wrote, “it is simplicity that emerges as the crowning reward of art.”

It is true for the virtuoso batsman of our time, too. Soto may be walking in the statistical footprints of some of the greatest hitters ever, but nothing gives him more pleasure than hitting a baseball perfect-perfect and watching it spin toward the wall in left center field and beyond.

“Three ninety-nine!” he yells in the batting cage in admiration of another master stroke. “Three ninety-nine all day long!” The simple flight of a perfectly struck baseball is the crowning reward of his art.