At a certain point in the 1980s, Amy Poon realised that her childhood was unusual. While her friends were pooling together their pocket money to share a McDonald’s milkshake, she was hosting them at her parents’ restaurant and signing off the bill. “I was certainly a friend with benefits!” she laughs now. But behind the scenes, it wasn’t always as glamorous as it seemed.

“Although we were surrounded by people the whole time, it was quite a lonely childhood,” Poon reflects. “My parents worked six days a week – they didn’t clock off at 5pm. I spent a lot of time at the restaurant.”

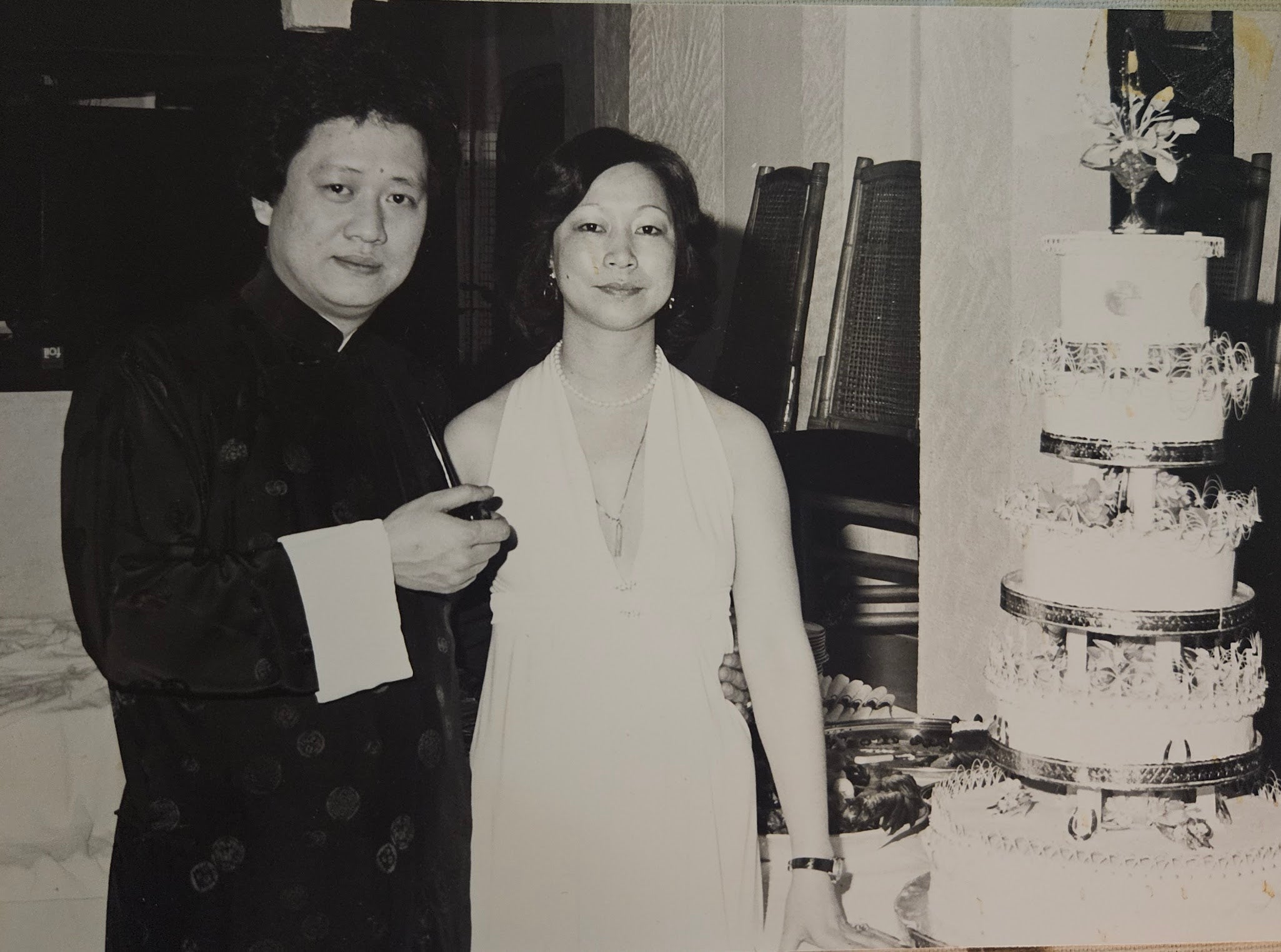

Her parents, Bill and Cecilia, opened Poon’s of Covent Garden in 1973, earning a Michelin star in 1980 and becoming one of London’s most iconic Chinese restaurants, helping to shift perceptions of the cuisine in Britain.

Around the same time, in Southall, Dipna Anand was also growing up in a restaurant. Aptly named, Brilliant Restaurant, the establishment was founded in Nairobi in the 1950s by her grandfather and brought to London by her father Gulu in the early 1970s. Specialising in Punjabi cuisine, it won plaudits from locals, critics and visiting dignitaries alike.

But for Anand, “The restaurant was like a second home,” she says. “Some of my earliest memories are of being in the kitchen, watching my dad cook.” She remembers stacking bottles, laying out paper tablecloths and learning to peel garlic, roll chapatis, and blend spices.

For decades, family-run Chinese and Indian restaurants like these formed the backbone of British high streets. But that generation of restaurateurs is ageing. The children who grew up in the kitchens and dining rooms their parents built now stand at a crossroads. Some are walking away entirely. Others are returning on their own terms. And many are asking: are we going to be the last generation? Does it all end with us?

Before Deliveroo and drive-throughs, the height of culinary excitement came in a foil tray or under a plastic lid (we all had a cupboard dedicated to stacks of the nation’s unofficial Tupperware). From Bradford to Aberystwyth, the local Chinese or Indian was often the first place we encountered a cuisine that wasn’t our own. They became our go-to celebrations, our weeknight crutches, our Friday night rituals. Sweet and sour chicken, tikka masala, prawn crackers, poppadoms. Anglicised, yes, but beloved all the same.

These restaurants didn’t just feed us – they became part of the nation’s culinary DNA. Many were opened by immigrants who found in food a way to survive, and then to thrive. Economic necessity became cultural cornerstone.

Later waves of immigration brought regional variety – Sichuan and Hunan joined Cantonese staples; Indian menus expanded to include Keralan fish curries and Punjabi dhaba classics. By the 1980s, nearly every British town had its Chinese or Indian staple – sometimes the only hot food available after 8pm, post-pub. The Sunday roast is still sacred, sure, but the Friday night curry has its own kind of reverence.

The classic story is one of sacrifice. Long hours. Gruelling work. Hospitality as a form of honour. “Running a Chinese restaurant didn’t rank with doctor, journalist, designer, engineer, musician, artist, management consultant,” says Poon. “Anyone growing up in a Chinese restaurant will attest to the punishing hours, the hard, often grimy work and the perception that it is something you do because you aren’t qualified to do anything else.”

That perception, of course, has always been false. Poon’s father plonked a glass kitchen in the middle of the restaurant in 1976 – decades before open kitchens were trendy – to counter the stereotype that Chinese kitchens were dirty or unskilled. He pioneered clay pot rice and introduced wind-dried meats. Diners remember his food with the kind of emotion usually reserved for weddings or funerals. The highly acclaimed chef “Henry Harris talks about a crispy garlic and chilli squid dish that he shared with his wife 39 years ago as a mouthful that changed his life,” Poon says. Michael Birt, one of the UK’s leading portrait photographers, is writing about a noodle dish he had at Poon’s in the Seventies for his memoir. Australian celebrity chef Iain Hewitson remembers a “wonderful chilli and garlic calamari dish”.

I know plenty who have stepped away, either because they wanted a different lifestyle or because they saw first hand how demanding the industry can be

But while the legacy might be revered, it isn’t always inherited. Many children of these restaurants grew up determined not to follow in their parents’ footsteps. “The industry wasn’t glamorous or well regarded, so it’s small wonder that a Chinese restaurant kid would want to pursue another avenue,” says Poon.

Of course, the allure of opportunities for their children was one of the main reasons these immigrant restaurateurs came here in the first place: so their kids might be able to attend university, pursue white-collar careers, step into lives their parents never had the chance to. In sociologist speak, it’s called the “immigrant bargain” – repaying your parents’ sacrifices by achieving professional success, even if it means turning away from the family business. Others call it “generational drift” or “brain drain”.

Anand sees it clearly in her own community. “The hospitality industry is incredibly rewarding but also very demanding,” she says. “Unlike our parents’ generation, who built their businesses through sheer hard work and long hours, many younger generations have seen first hand the sacrifices involved – late nights, unpredictable schedules and the physical toll.”

“There’s also been a shift in aspirations. Many second-generation British Indians have had access to higher education and a wider range of career options. In some cases, there’s also a perception that hospitality isn’t as prestigious or lucrative as other professions.”

It’s not always a rejection – sometimes just a redirection. “Some of my peers, like me, have chosen to stay in hospitality because it’s in our blood,” she continues. “But I know plenty who have stepped away, either because they wanted a different lifestyle or because they saw first hand how demanding the industry can be.”

Poon, for one, swore she would never go into the restaurant business. “It was not a lifestyle I wanted for myself and my family,” she says. She worked in advertising, ran a champagne bar in Singapore’s red light district and wrote a couple of silly books – “the kind you put in the loo”. It was only in her forties, with two daughters and a sense that it was time to “grow up and put down some roots”, that she felt the pull back. “There was this gift of an opportunity that I was beginning to grasp,” she says. A talking-to from a friend sealed the deal: “She told me off for ‘faffing around’!”

Anand, by contrast, was all in from the start. “My family never expected me to take over the business… For me, it was always a natural choice,” she says. Her brother took longer to find his way back, but now they run the business together.

Still, the shape of the business is changing. Brilliant Restaurant is closing its doors after half a century. In its place, Anand and her brother are opening a gastropub. “We’re not stepping away from hospitality,” she says. Instead, “we are transitioning”, building on what their family started. “That’s the beauty of hospitality: it allows you to adapt while keeping your roots intact.”

The pressure to adapt isn’t just emotional – it’s economic. “The restaurant industry has changed massively, and keeping a family-run restaurant going has become more challenging than ever,” Anand says. “One of the biggest shifts has been the rising costs across the board: ingredients, gas, electricity, materials and wages.”

“The key to survival in this industry is innovation,” Anand says – but not all innovation works in a restaurant’s favour.

Delivery apps like Deliveroo and Uber Eats may have revolutionised how Britons order food, but they’ve done so at a cost. Commission fees of 25 to 35 per cent can gut already slim margins. To offset this, many raise prices on the apps, making their food appear disproportionately expensive and sometimes driving customers away. Worse still, these platforms act as middlemen, stripping restaurants of access to their customers, their data and their loyalty. Convenience, it turns out, isn’t always mutual.

Poon, too, has found herself innovating. Rather than reopen a traditional restaurant, she launched Poon’s London with pop-ups and a sauce range. Her Wontoneria at Spa Terminus sells freshly prepared wontons alongside Asian pantry staples. She has no grand plan. “I’m not that strategic!” she laughs.

Yet the outcome is something modern and personal. “The family name isn’t something rigid. It’s an evolving, living thing,” she says. “I couldn’t have done any of this without the platform that my parents have provided… I always feel there are shades of Gatsby in what I am doing, not in a bad way, but I do recognise what came before so I can do what I do.”

The traditional Chinese takeaway is dwindling in numbers but I think there has been evolution

If that sounds romantic, it is. But there’s pragmatism too. Very few new family-run Chinese or Indian restaurants are opening in Britain today, and many of the old guard are quietly closing. “Back then, while it was still hard work, the overall costs were lower, and there was a stronger pipeline of skilled chefs,” Anand says. Customer habits have changed, too. “People expect quicker service, more convenience and competitive pricing, which can be difficult to balance while maintaining quality,” she says. “At the same time, diners are more adventurous and competition has increased.” The brain drain is being felt here, too. “Fewer younger people are entering the industry, and the skilled chefs who understand authentic Indian cuisine are becoming harder to find.”

She’s hopeful the next generation will adapt. But she’s also honest. “I sincerely hope that family-run curry houses will still be around in 20 years, but it’s not looking very promising,” she says. “These restaurants are more than just places to eat, they represent generations of tradition, passion and hard work. They’ve played a huge role in shaping Britain’s love for Indian food, and it would be a real loss if they started disappearing.”

Poon is slightly more optimistic. “Dining trends are fickle and cyclical,” she says. “The traditional Chinese takeaway is dwindling in numbers, but I think there has been evolution.” She points to new-wave concepts like Three Uncles, a slick Cantonese roast meat shop that brings the flavours of Chinatown’s hanging-duck windows into a more modern, grab-and-go setting. And Rice Guys, a former street food stall turned delivery-focused brand offering modern takes on classic dishes like char siu and mapo tofu. Both fuse the flavours and comfort of traditional Chinese cooking with a fast-casual model and contemporary branding. “These are brilliant, thriving, delicious examples of the Chinese takeaway, brought into the next generation,” says Poon – familiar in flavour, but reimagined for a different time.

Both agree that success today lies in finding new ways to preserve old stories. Poon puts it beautifully: “All sorts of people have come forward to share their most wonderful memories of eating at Poon’s, of meeting my parents, of what my father cooked for them, of how my mother helped them.”

“Then there are my own stories of meeting people like Sean Connery and Barbra Streisand, who I didn’t think were of any interest to anyone at the time!”

Anand believes innovation that preserves stories and traditions is the way forward, too. “Some of the best Indian restaurants today are chef-driven concepts that push boundaries while still respecting tradition. I think the future will be a mix.”

So, is this the last generation? Maybe not. But it is a different one. One that grew up between tandoors and textbooks, between clay pots and career days. One that knows how much it cost to build these legacies – and how much it might cost to let them go. Whether they choose to inherit, reinvent or walk away, one thing is clear: what their families built still matters to us as much as it does to them. These were the places that fed us on quiet Friday nights, long before food delivery became an algorithm. Many may be disappearing, but those that endure are finding new ways to adapt – evolving without forgetting where they came from. And neither will we.

£30 roasts, Michelin stars... has the gastropub lost the plot?

King Charles dragged into Prince Andrew spy scandal

Stormy skies, secret cocktails and perfect roasties in an unlikely seaside town

Noor Murad’s running the London Marathon – and rice is her secret weapon

Why Greek yoghurt and bananas aren’t the good breakfasts you think they are

Why your favourite jam could soon cost more – and it’s not just fruit to blame