While travelling through parts of North Africa and the Middle East 20-plus years ago, I experienced a moment of dread well known to travellers through the ages: just a few weeks into the trip, which would last nearly seven months, I finished the two books I had brought with me.

At the time, I was taking Arabic classes and renting a room from a man in Giza, Egypt. Perusing his sparsely stocked bookshelf, I noticed an old hard-bound edition of TE Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom. “Take it, take it,” he insisted. A foreign friend had left it behind, he said, and it was of no use to him; although he spoke English fluently, he couldn’t read it at all.

Among the many things that struck me about this remarkable work were Lawrence’s descriptions of Wadi Rum, in Jordan. He wrote of a wall of rock “sheering in like a thousand-foot wave towards the middle of the valley”, of sharp hills forming a “massive rampart of redness”, of sandstone domes and crags and “parallel parapets” that “ran forward in an avenue for miles”. It was, he declared, an “irresistible place”, a “processional way greater than imagination ... Our little caravan grew self-conscious, and fell dead quiet, afraid and ashamed to flaunt its smallness in the presence of the stupendous hills. Landscapes, in childhood's dream, were so vast and silent.”

Though I had no plans to visit Jordan, mostly because I had very few plans at all, I knew I needed to see this place for myself. After travelling through most of Egypt, I crossed the Sinai Peninsula by public minivan, then the Red Sea by ferry. Once in Wadi Rum, a 4x4 driver dropped me in the middle of the desert that Lawrence had, if anything, undersold. Armed with a map, some local advice and my background as a wilderness guide, I spent a week trekking alone over salmon-hued dunes and among monumental massifs, from one hidden watering hole to the next, until I made it back to the main village.

Immersing myself in this fantastical landscape and sharing tea and food with the Bedouin I met there were among the most meaningful and formative of my early travelling experiences, fueling a desire and laying the mental infrastructure for future expeditions on foot – and by camel – in remote places. And I only found my way there because I had run out of reading material.

Since the coronavirus pandemic first hit pause on international travel, there has been time to reflect on how to travel better once it feels safe enough to get out there again. Growing numbers of travellers, for example, are taking steps to mitigate their environmental effects. Others are leaning toward culturally immersive trips, getting to know a place and its people while putting dollars directly into local economies. And new hygiene requirements have become commonplace priorities.

Adding to that list, I’d suggest leaving e-readers at home and smartphone libraries empty on all but short trips, and taking physical books instead.

At a glance, this advice may seem counterintuitive. After all, the great selling point of e-readers is their ability to store tons of books on one small device, a convenience when packing light. But physical books have some practical advantages of their own. They can’t break, never need to be charged, aren’t likely to be stolen and, if one is lost, you’re out no more than a few bucks. Plus, in a pinch, you can use the pages you've already read to start a campfire.

The best reason to favour paper over pixels, however, especially on a long trip, is its relative inconvenience, the fact that you will run out of reading material and have to look for a new book wherever you are in the world. This builds an element of unpredictability into a trip, signalling an openness both to the search for and discovery of whatever book happens to next cross your path.

The serendipity involved represents a key element of the art of travelling: not needing to control or preprogramme your experience, letting things unfold organically and taking the chance to be delighted by the unexpected. The most memorable moments of any trip, the ones that give us stories to tell beyond reciting lists of sights seen and meals eaten, are usually unplanned. Because longer adventures involve journeying through our own interior landscapes in addition to the physical places we visit, and because the books we read influence the terrain of our imaginations, I want to leave room for surprises on the literary voyage that parallels the one I'm making on the ground.

Although Wadi Rum moments – when a randomly found book alters the course of a trip and, perhaps, one’s life – happen from time to time, they are rare, and they aren’t really the point, anyway. It’s the embrace of the spontaneous and where that can lead that truly adds value to one’s travels. As it happens, I’m frequently gratified by the books I stumble upon, which I usually wouldn’t have thought to pack on an e-reader, had I brought one.

After finishing Seven Pillars while in Egypt’s Siwa Oasis, I approached a British traveller in a restaurant and asked whether he had any books he was done reading. I traded Lawrence for Thomas Pynchon (V) and struck up a friendship with someone I would go on to travel with for a few days. In Morocco, I burrowed through a dusty used bookstall in a town on the edge of the Sahara, which mainly sold titles in Arabic and French, and somehow emerged with Geek Love (in English).

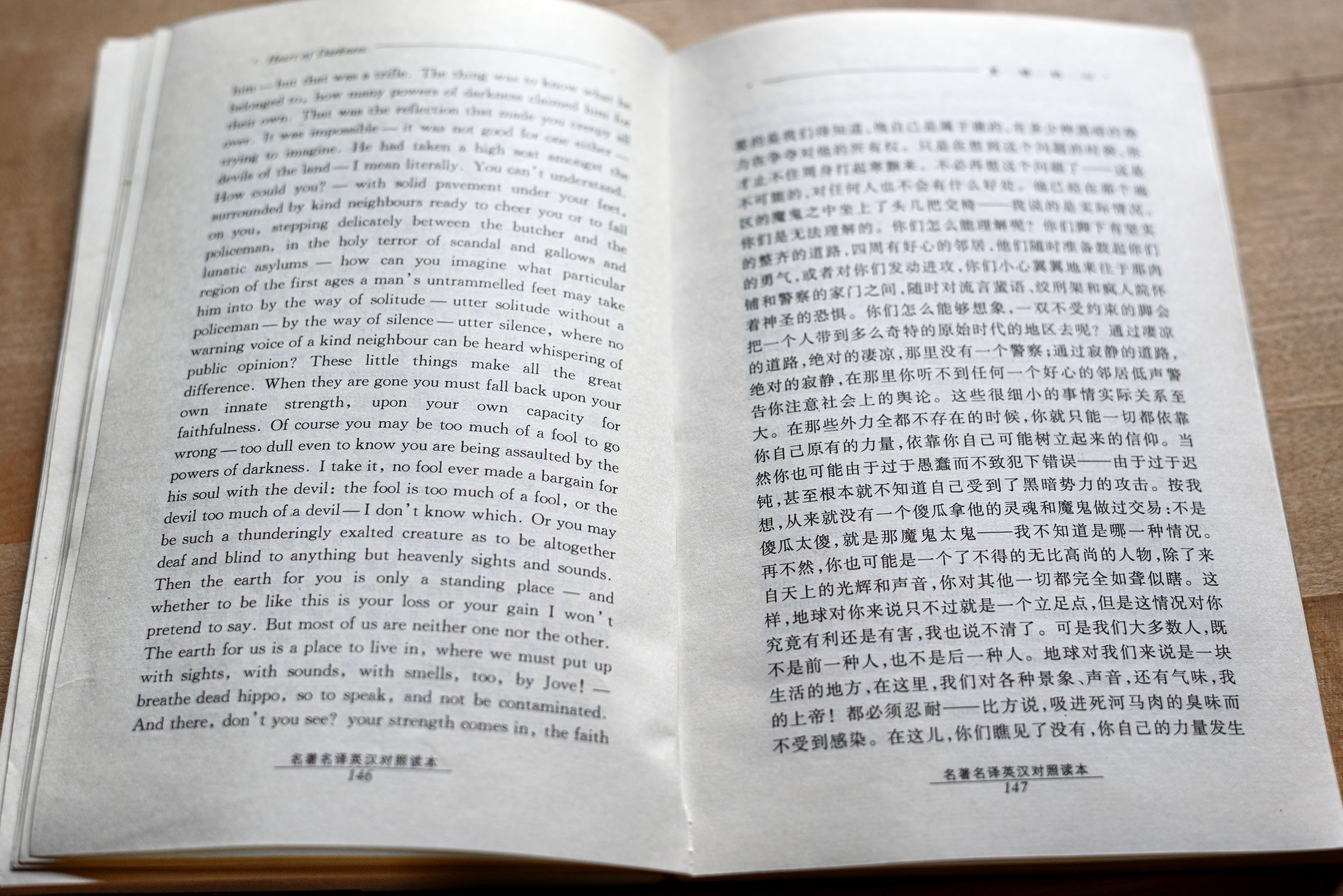

I once ran into two young Americans whose ties and name tags looked out of place on the streets of Ulaanbaatar; after a fascinating conversation about their mission to Mongolia, I walked away with a highlighted copy of The Book of Mormon, plus directions to an odd little shop, where I picked up a bilingual edition of Heart of Darkness with pages of Chinese characters facing those in English.

And after I had idiotically resisted it for years, because how could anything so popular with eight-year-olds be that good, Harry Potter entered my world via a street cart in Ahmedabad, India. Other titles that have come my way include Gandhi’s autobiography, Frankenstein, East of Eden and The Beach.

Sometimes, of course, you may hit a brief dry spell or pick up a dud, which, rather than sowing doubt about this endeavour, suggests an altruistic rationale for carrying physical books: to keep a healthy supply of them circulating in the travel bibliosphere, refreshing guesthouse book exchanges, restocking youth hostel libraries and supporting trade among travellers.

As you thumb through that worn paperback that found its way into your hands, you may wonder: “How many other people have read this book? How far has it travelled? And where will it go after I've passed it on?” The book becomes an object with a life of its own, connecting you in a small way to the mysteries of life on the road. Those kinds of questions, and that kind of connection to the noumena of travel, would never arise from a downloaded file on a digital device.

© The Washington Post