Complicated pieces of legislation rarely live up to the glitzy names scrawled across the first page. But even by that familiar standard, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 is going to disappoint anyone excited by its title.

The bill, introduced last week after a long-awaited deal was struck between Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D–N.Y.) and moderate Sen. Joe Manchin (D–W.Va.), was pitched as a way to lower costs for consumers while also reducing the federal budget deficit and spending billions on environmental initiatives meant to combat climate change.

It didn't take long for a problem to present itself.

"The impact on inflation is statistically indistinguishable from zero," concluded the Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM), a number-crunching policy center based at the University of Pennsylvania. In fact, if the bill's passage had any impact on inflation in the short term, it would be to increase it very slightly until 2024, according to the group's preliminary analysis, released on Friday.

Other parts of the Inflation Reduction Act would do what Manchin and Schumer claim. According to the PWBM report, the bill would reduce future deficits by a cumulative $247 billion over the next decade and would marginally reduce the national debt as a result. It would spend about $370 billion on new environmental and climate initiatives. It would pay for all that by raising taxes and by boosting IRS enforcement, in hopes of chasing down revenue that currently goes unpaid.

But again, the Inflation Reduction Act won't actually reduce inflation.

The Schumer-Manchin deal also appears to violate President Joe Biden's oft-repeated promise not to raise taxes on households earning less than $400,000 annually.

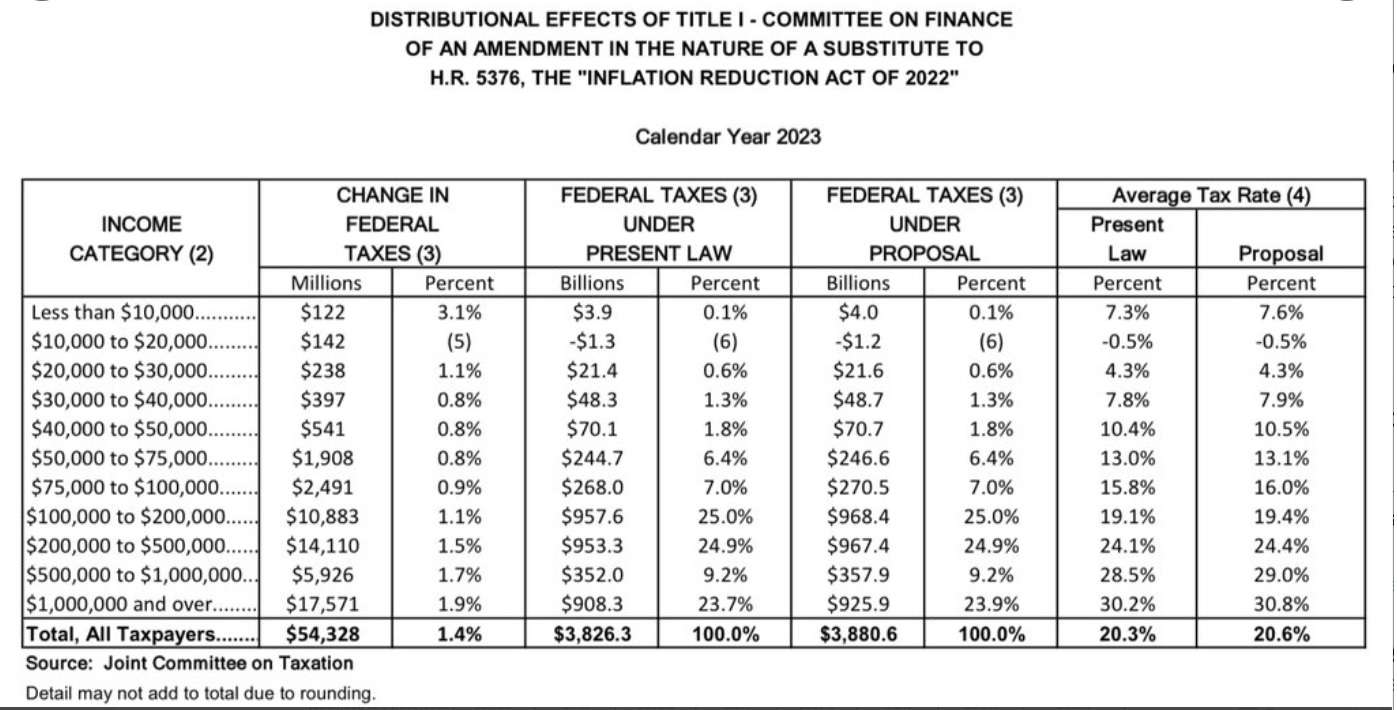

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), a nonpartisan agency within Congress, the Inflation Reduction Act would hike taxes by about $54 billion next year. More than $16 billion of that total would come from households making less than $200,000 and another $14 billion from households earning between $200,000 and $500,000. (The JCT's brackets don't cut off at the $400,000 level used by Biden.)

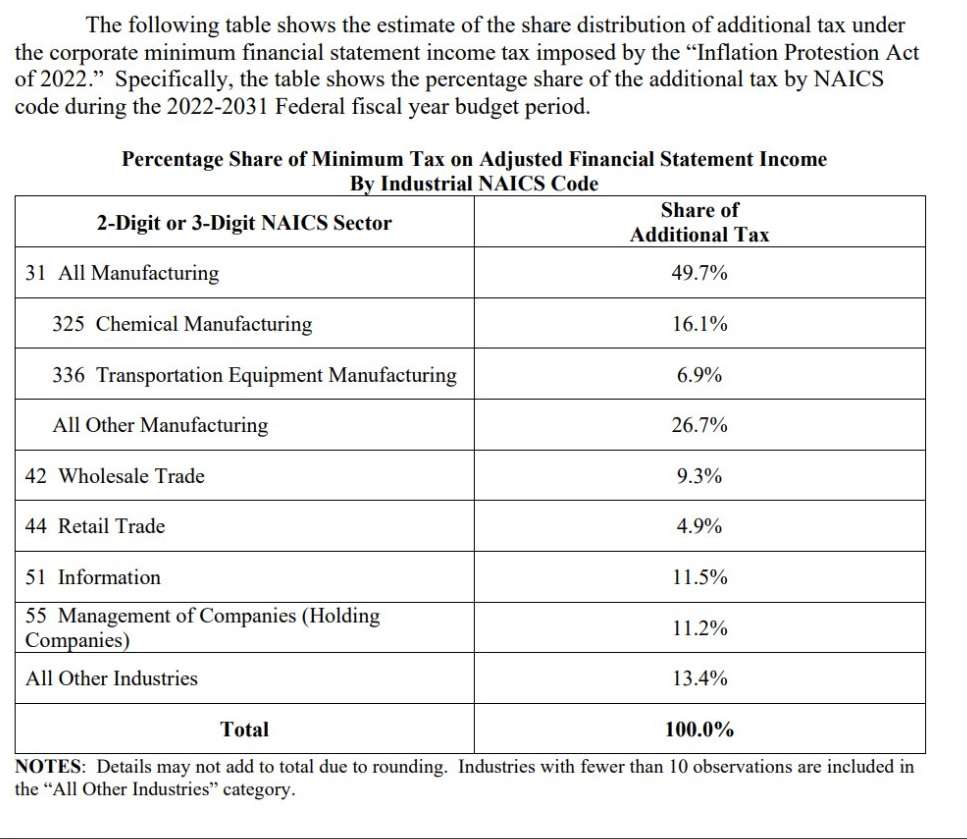

Meanwhile, other provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act would sit uncomfortably beside Congress' other major initiatives this year. Just last week, the Senate voted to hand $66 billion in new subsidies to computer chip manufacturers as part of an overall effort to boost domestic manufacturing of high-end electronics. But the corporate tax increases included in the Inflation Reduction Act would fall most heavily on the manufacturing sector, according to the JCT.

As a result, senator voting for both bills would effectively be voting to hike taxes on the very industries they just voted to subsidize. So much for improving American manufacturers' competitiveness!

Passing contradictory and counterproductive pieces of legislation would be nothing new for Congress, of course. So the biggest political problem for the Inflation Reduction Act remains the disconnect between the bill's premise and the impact (or lack thereof) that it would have on inflation.

Manchin is certainly trying to sell it. "This is all about fighting inflation," the senator said during an appearance yesterday on ABC's The Week. "Inflation is just absolutely destroying families across West Virginia and across America."

Manchin's right that Americans are struggling to deal with high costs. But it's not clear how raising their taxes will help with that.

The post The 'Inflation Reduction Act' Won't Actually Reduce Inflation appeared first on Reason.com.