A new translation of a 2018 book by French science historian Thibault Le Texier challenges the claims of one of psychology’s most famous experiments.

Investigating the Stanford Prison Experiment: History of a Lie, published recently in English, documents serious limitations of the study – including that student “guards” were actually coached to dehumanise their “prisoners” – and asks how such a flawed experiment became so influential.

An infamous ‘prison’ in a university basement

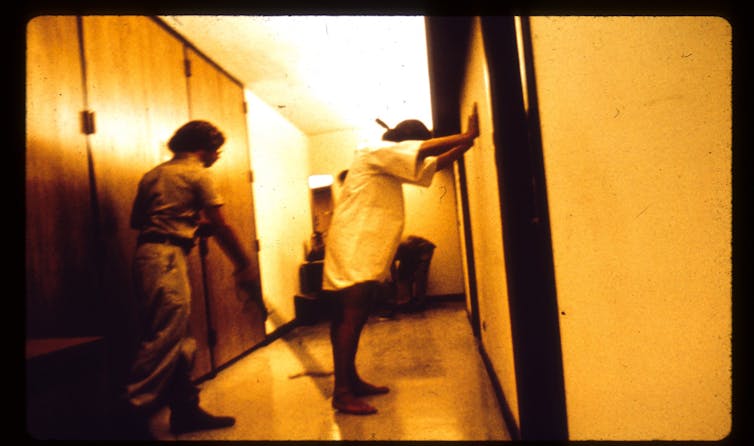

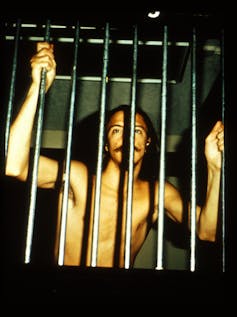

You’ve likely heard of the Stanford prison experiment. In 1971, 24 young male volunteers were randomly assigned to the roles of “inmates” and “guards” in a pretend prison in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology department.

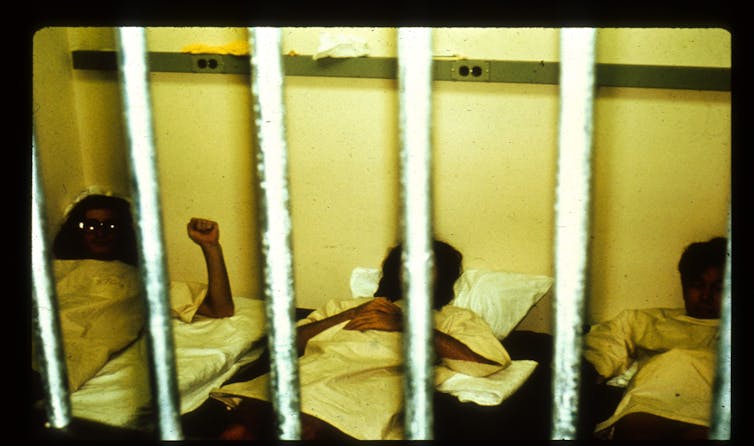

The situation quickly got out of control. By day two, the volunteers playing the role of guards had begun psychologically torturing their prisoners.

Stripped naked, hooded, chained, and denied food and sleep, the prisoners became traumatised, with half suffering nervous breakdowns so that by day six the experiment – planned to last two weeks – was called off.

The experiment was conducted by social psychologist Philip Zimbardo, who died last year at the age of 91. He argued that the transformation of seemingly normal people into cruel guards and passive prisoners was proof that social situations have the power to corrupt human behaviour.

His sensational findings and the dramatic story of the experiment, illustrated with photos of uniformed guards in aviator shades and batons standing threateningly over cowering and hooded prisoners, made Zimbardo and his experiment famous.

Since it was conducted over five decades ago, the lessons from the experiment have been applied to a burgeoning number of situations beyond prison. By 2007 Zimbardo used it to explain corporate fraud, military torture, cult behaviour and even genocide.

A recently published English translation of French academic Thibault Le Texier’s 2018 book unearths a more complicated and troubling story of the famous study. It casts doubt on Zimbardo’s reliability as a narrator of his own research.

Criticisms of the experiment are not new, with critiques of its methodology and Zimbardo’s argument that situations can overpower our personalities appearing as early as 1975. But Le Texier’s detailed findings, available in English for the first time, offer a full account of events behind the scenes.

Coached to be brutal

Using archival sources, unseen video footage, transcripts and extensive interviews with participants – including the guards, prisoners and members of the research team – Le Texier creates a day-by-day account of the experiment as it unfolded.

Far from being swept up in the situation, archival sources show the guards’ brutality was rehearsed. Contrary to official accounts, before the experiment they were coached by the research team in how to create a psychologically hostile environment.

Zimbardo gave the guards a list of rules to impose and procedures aimed at dehumanising prisoners. Once the experiment began, staff encouraged guards’ aggression and reprimanded those who were too lenient.

In contrast, the prisoners had little preparation. Most envisaged spending their prison time reading or watching TV in their cells. So they were dismayed at the humiliations, the deprivation of cigarettes and books and other distractions, and the frequently arbitrary and changing rules.

Neither the prisoners nor the guards responded in the same way to the situation. Some guards played their role with zeal. Others sympathised with the prisoners, smuggling in food and cigarettes. One quit.

Some prisoners cooperated, some resisted, some revolted. One staged a hunger strike. Most wanted out but soon discovered that despite being told beforehand they could leave at any time, this was not the case.

Only a medical or psychiatric emergency would secure their release. Le Texier found that three rather than five prisoners were released on the basis of emotional distress and that at least one had faked it.

The experiment was terminated because it was at risk of failure.

Le Texier found that by day six the guards were increasingly impotent in the face of resistance from the remaining prisoners. An unexpected visit from a lawyer raised concerns about the legality of holding volunteers against their will. These were both factors in the experiment’s abrupt termination.

Enduring grip on the collective consciousness

As Le Texier points out, Zimbardo’s media savvy, his skill as a populariser, his university’s support and a largely uncritical acceptance of his findings have been powerful factors in the enduring fame of the experiment.

It continues to exert a powerful grip on the public imagination, largely through the promotional flair of its creator.

Le Texier’s book raises important questions about the cultural and political factors that shape research. For example, Zimbardo’s study was conducted during a period of intense anti-authoritarianism and against the backdrop of the 1971 Attica prison riot, the deadliest prison uprising in the United States.

Le Texier’s book also has much to teach us about science communication and the potential of media-savvy scientists to construct and promote a powerful narrative.

The Stanford prison experiment can be excised or acknowledged for its overblown claims in textbooks, but will it ever be excised from the public imagination? Unlikely.

As Le Texier writes, the experiment has gained such a grip on our collective consciousness because while its findings might be false, it appears to offer a profound moral lesson.

Zimbardo’s knack was tapping into our hunger for answers to the big questions of our time. It may be theoretically vacuous, a morality play disguised as science. But the fame of the Stanford prison experiment endures because it appears to shed light on how good people can become evil. And that always makes for a good story.

Gina Perry does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.