Katya’s brain was swollen. She had been blown up so many times she had hernias on her spine. Her whole skeleton was twisted and distorted after being thrown about like a doll.

She often stuttered. She had an explosive temper after years as a special forces medic. But things got better when she went to “Valhalla”.

She didn’t take the usual route to the Viking Hall of Heroes, where she undoubtedly belongs, by being killed on a Ukrainian battlefield. Instead she hitched a hallucinogenic ride.

On ketamine.

The illegal party drug, animal tranquiliser and battlefield anaesthetic is being used to bring Ukraine’s living dead back to real life. Pioneering ketamine therapy offers hope of a fast-track cure for post-traumatic stress disorder in a nation grappling with widespread trauma.

Katya is about 5ft 4in. At 23, she is a veteran of years of extreme combat in Ukraine’s most secretive and elite units, having enlisted at 19 and joined the marines. She’s alternately diffident and steely – holding an unblinking gaze with the ease of a killer.

She spent two years running medical evacuations under fire in Ukraine’s special forces. She remembers the first time she was hit by an explosion and thrown several yards, smashing her head.

She also remembers when a 155mm artillery shell crashed into the ground next to her but did not explode. The rest of her injuries are a blur: “I got concussions on every mission.”

Brain scans of physical traumatic brain injury look very similar to PTSD scans. The symptoms can be similar.

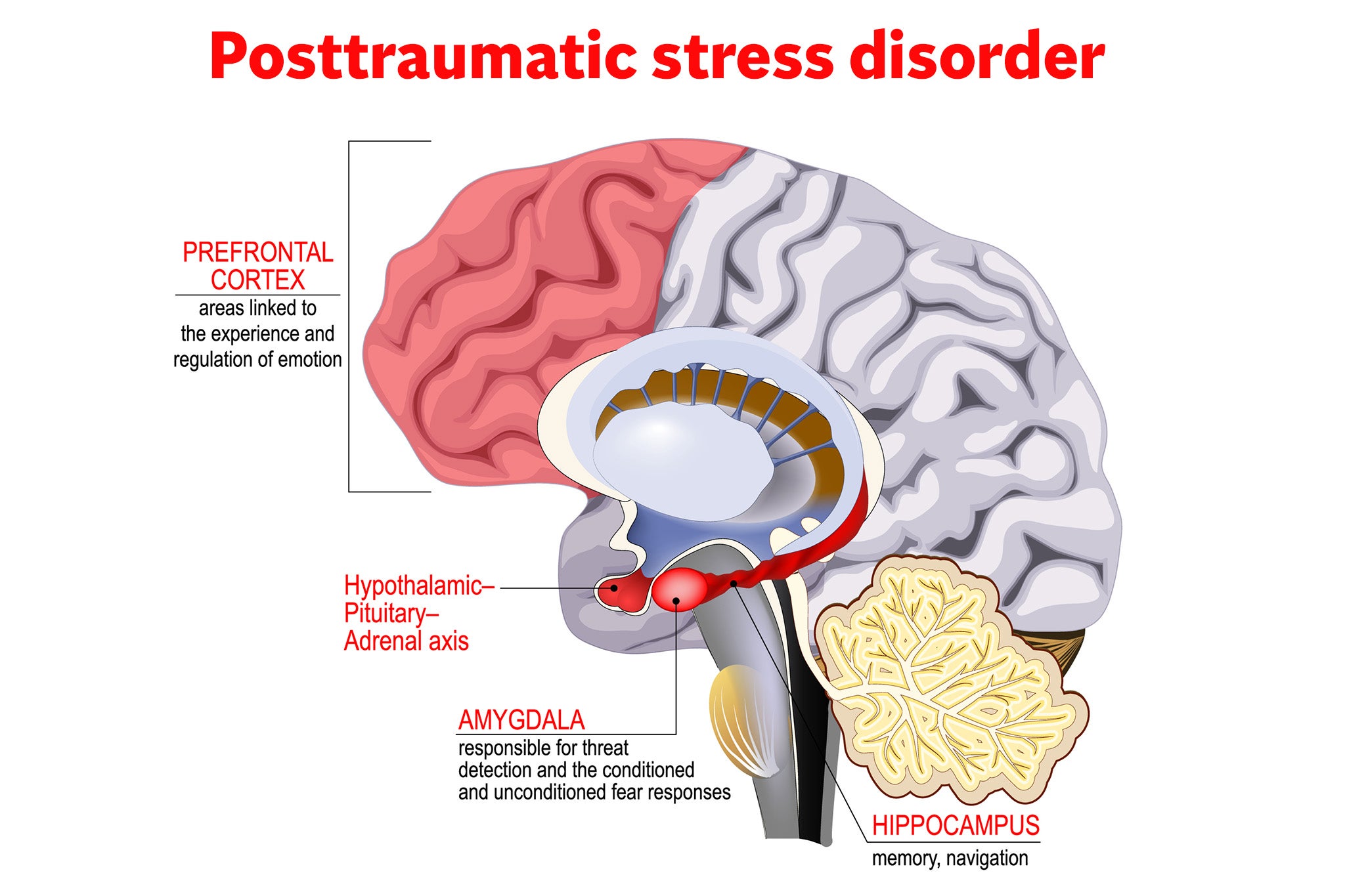

PTSD is a vicious circle of glitching between the brain’s memory bank – the hippocampus and the amygdala that controls threat responses – and the front of the brain that’s supposed to put data into rational context.

Sufferers endure hyper-vigilance, distorted threat responses and cognitive decline. It can feel like being a ghost – or living in irrational agony.

“I started losing weight in March 2023,” Katya explains.

“We had an active phase in Bakhmut. I was working with the dead and injured. I was so mentally and physically exhausted that I weighed 44kg. I could not sleep. I was very aggressive.”

Katya also suffered the trauma of grief while on active duty with the death of her older brother in the spring of that same year as he led an assault on Russian infantry.

“After my brother died, I became very aggressive and scatterbrained,” she recalls. “I don't remember two months of my life at all – it was very intense.

“Mission after mission, without rest. I was so exhausted, I could not sleep, I could not talk to people. I was stuttering, I had constant headaches, I was feeling inadequate. I was not stable and coherent. I was not in control.”

She, like many others, decided to venture to the outskirts of Kyiv where Ukrainian medics are treating veterans with PTSD at the Lisova Polyana psychiatric hospital.

Therapists there have worked with more than 1,000 former prisoners of war, many of whom have endured intense torture in Russia.

Traditional therapies like cognitive behavioural therapy can take “two, three or five years”, says neurologist Dr Kseniia Vosnitsyna, head of the hospital.

But therapy under close supervision using ketamine has had staggeringly quick results, she explains. Dr Vosnitsya, who has pioneered a government programme in the use of ketamine, wants to open up research here into psychedelics.

“We are constantly searching for more tools that can be used. And it’s not just about the CBT, classic psychotherapy can last two-three-five years. So we need to find something that works fast.

“That’s why [we are interested in] psychedelic therapy; it gives faster results. And we need it because we need to get people back to the front line faster.”

The military imperative is stark. Ukraine is short of soldiers. They need to be repaired and sent back to fight again. Up to 80 per cent of the troops who come through Lisova Polyana end up back in the army. Ketamine could speed that process up.

Studies in the UK by teams of scientists at Imperial and Kings College in London have shown remarkable success in using psychedelics to treat depression and PTSD.

But the use of ketamine in medical care has been easier to apply in Ukraine and elsewhere because it doesn’t require special licensing.

Patients get intense therapy before, during, and after their session under the influence of ketamine. They take the drug under supervision, often blindfolded and wearing earphones playing soothing music.

They enter a conscious state that takes them on a deep dive into their subconscious.

The drug, like psilocybin (also known as magic mushrooms), LSD, and ayahuasca – all therapies being investigated elsewhere – adds neuroplasticity to the brain, making it able to learn quicker.

There is growing scientific evidence that these therapies effectively rewire the human mind and repair burned-out circuits.

But it is not straightforward.

“This experience may be painful. It's not an easy walk in the park,” says Iryna Feofanova, a ketamine therapist at Forest Glade where traumatised soldiers wander the corridors, sit silently in the woods and play silent games of pool in echoing halls.

“It's not some euphoric experience. Mostly it's a painful, prickly experience. But it's a very important one.

“From what I hear from my patients, it's bearable. It's painful, but it's something you can get through, feel through.”

For Katya, who had been so exposed to death, the end of life was less confusing than the living of it.

“It was very important to me to stop surviving and start living,” explains the former marine sergeant. “I had no goal - my only goal was to kill more Russians, to win, and then I will figure it out. But I never expected to live so long.

“I thought I would be dead already and I would not have these questions [about a future life]. But it turned out that I did not die, and I had to deal with them.”

Katya, who is now studying business, has gone through multiple ketamine sessions under the guidance of Ukraine’s pioneer in psychedelic therapy Dr Vladislav Metranitsy, who says that anecdotally, he is seeing successful treatment of about 70 per cent of PTSD patients.

“It became clear that standard first-line, so-called first-line treatment – which is psychotherapy plus antidepressants – does not work efficiently.

“It's estimated that about 60 per cent of people who suffer PTSD, and veterans particularly, are not responding to first-line therapy,” he explains.

“A very important mechanism for ketamine and other psychedelic actions is that it creates a state of enhanced neuroplasticity which continues for several days after infusion.

“During these days people’s brains usually better process information in general and dramatic information … people may have some insights, new understandings, take new decisions.”

In Katya’s experience, the ketamine sessions have brought her a spiritual warmth and new experiences “from different religions”, to visions of Judaism’s “tree of life”, flying through space and meeting old friends.

With the help of the drug she says, she experienced hallucinations of nuclear mushroom clouds and plumbed the depths of her most traumatic experiences that brought her back to the present.

“I travelled from Valhalla to space. I learned to live now and to have a vision for the future.”