At the foot of a very steep hill in the middle of the Forest of Bowland is the church of St Michael’s, where an archive of black-and-white photographs records the work of former parish priest Thomas Brangwin Reid. His name may not trip of the tongue like Sir Bradley Wiggins or Hugh Carthy but, like them, this country parson spent many hours cycling in this beautiful and lumpy patch of Lancashire (UK).

Whereas Wiggins did his winter training here on the way to his historic victory in the 2012 Tour, and a teenage Carthy honed his climber’s physique on the local hills before joining the professional peloton, the Reverend ‘Tommy’ often cycled up to 60 miles a week, battling winter weather and steep gradients on the way to the remote, rural dwellings and farms of his 370-strong flock of parishioners.

The photographs show him arriving in cloak and cassock, occasionally carrying with him the two-metre processional cross he had made from a hay rake. Though many of these visits were on foot, the vicar eventually bought a bike, reported the Clitheroe Advertiser. In the same report, vastly underestimating the calorific demands of the average cyclist, local landlord Brian Tidegate commented: “Most people are going to have a meal ready for the vicar. He’s going to have a job coping with that.”

The going gets trough

Reid retired aged 70 in 1974 and it’s a sign of the times that the current incumbent at St Michael’s now uses a less humble form of transport – a notice outside the church says: ‘Parking for Vicar only’.

After paying my respects to the cycling clergyman, I’m now saying a silent prayer of gratitude that the 14% incline opposite the church – which Reid had to tackle on his way back to his vicarage after every service - isn’t on today’s route. At this stage I’m blissfully unaware that I’ll be paying an even greater penance for all my sins, cakes and beers on a series of much tougher tests.

The first of these is the Trough of Bowland, where the heather-clad slopes appear to gang up on you as the road twists and rises. By the time you reach the cattle grid at the top, you have climbed 140 metres in just over two kilometres with a peak gradient of 14%, and feel like the last glob of toothpaste that has been squeezed from the tube.

The descent is a shallow, sinuous affair that eventually levels off, sandwiched between a boulder- strewn stream and ancient stone wall. Occasionally a car or van is parked up on the verge, shattering the ageless charm of the scene. I can’t help feeling the drivers are the kind of people who would visit the Louvre just to use the free WiFi.

Other than that, there has been very little motorised traffic on this largely single-lane road, though I am developing an overly familiar relationship with a countryside ranger who has passed me several times in both directions in his big, ugly wagon.

The Forest of Bowland has been designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty for the last 60 years, yet thankfully seems to have escaped the deluge of tourism that afflicts the Lake District on the other side of the M6.

This feeling is reinforced as the road widens and I emerge onto a windswept plateau offering views of Blackpool Tower and the Irish Sea to my left. I’m close to civilisation and yet surrounded by only wide, open expanse.

Bewitching history

I stop at the Jubilee Tower, a Victorian folly offering panoramic views of Lancaster, Morecambe Bay and the Cumbrian mountains to the west, and the Bowland Fells to the east.

A plaque in the car park on the opposite side of the road informs me that on this site in 1973 the remnants of a coffin, body and shroud dating back to the Dark Ages – 600 AD – were discovered (and are now on display in Lancaster City Museum).

Adding to the sense of history is the knowledge that the route I’ve cycled so far today was also taken by the ‘Pendle Witches’ in 1612. They were a group of 10 villagers accused of various acts, ranging from ‘causing madness’ to killing a horse by ‘riding it to death’, who were being transported to Lancaster to face trial and, ultimately, death by hanging. I’m disappointed that, despite this route’s rich heritage, I haven’t seen a single broomstick along the way.

From here there is a fast, pulse-quickening descent down to Quernmore. The road kinks abruptly to the right, forcing me to slam on the brakes, which is just as well as the junction I am looking for has appeared unexpectedly quickly.

In the village of Caton I have to briefly join a traffic-choked A-road before crossing the River Lune. I turn on to a single-lane road that threads across an idyllic stretch of hillside full of picnicking cyclists and inquisitive sheep.

This is what I’m really enjoying about this ride so far: I’ve seen more cyclists and sheep than cars. And of those cyclists, as many appear to be enjoying the simple pleasure of riding a bicycle through glorious scenery as chewing their stems.

Cat and rat run

I’ve joined National Cycling Network route 69 (Morecambe to Grimsby) and enjoy the sweeping views across the river, passing homes and farms with such evocative names as ‘Hawkshead’, ‘Kestrel’ and ‘Windhover’.

I eventually re-cross the River Lune and enter the handsome, stone-and- slate village of Hornby, welcomed by a distinctive crest above a fountain featuring a cat with a rat in its mouth. This is all that remains of a bridge that once carried the Little North Western Railway, known as the ‘Cat and Rat’ railway because of the owner’s gratitude to his feline friends for clearing his home – Hornby Castle - of an infestation of vermin.

I contemplate stopping here for lunch. The village tearoom looks welcoming enough but there is no seating outside and I’m craving vitamin D, so I continue to Wray, the last outpost of civilisation before my route will take me across the most desolate and exposed stretch of the ride.

The blackboard outside the Wray Village Store announces, ‘Groceries, fresh fruit and veg, household goods, local arts and crafts, hot and cold drinks, sandwiches, detergent refills, cycling spares.’ There’s also a bench and table outside, so that clinches the deal. Sure enough, squeezed in between a fridge of soft drinks and shelves of pet food are racks of tubes, tyres and spray cans of WD-40.

In between buying my tuna mayo sandwich, can of Coke and a fl at white, I learn the shop was saved from closure by villagers raising £55,000 to take it over. It stocks cycling spares because part-time manager Malcolm Evans has an alter ego – ‘Mal The Bike Guy’ – who promotes cycling as an inclusive, active and sustainable transport option. “We get a lot of riders passing through the village,” he says. “Bowland is a beautiful place to ride a bike but there’s lots of livestock grazing so take care on those descents.”

How to get there

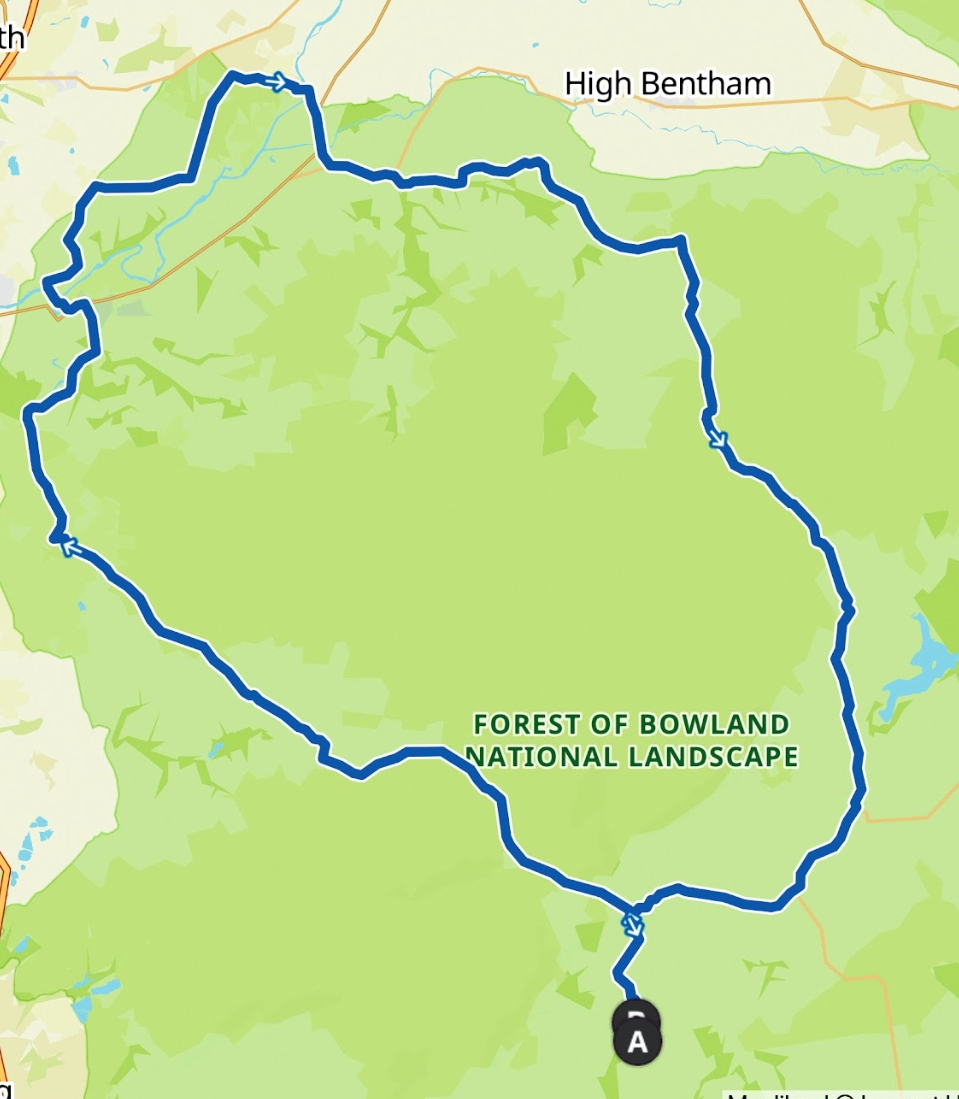

● By train The nearest railway station is Clitheroe, 12km from Whitewell, the start/fi nish of our route. There are direct trains from Blackburn, Bolton and Manchester stations. Connections to the West Coast main line are from Manchester Piccadilly.

● By car Whitewell is a 40-minute drive from both Preston and Blackburn. As a loop, you could pick it up from Caton, just off junction 34 of the M6 near Lancaster.

Where to stay

We stayed at – and started our ride from - the beautiful Inn at Whitewell, a former hunting lodge that off ers a range of rooms and converted coach houses. We kept our bike in our coach house and used the ‘dog cleaning station’ to spray it clean at the end of our ride. The Inn has a great restaurant and beer garden overlooking the River Hodder. Details: innatwhitewell.com

Where to eat

We enjoyed a fabulous fuel-up on the eve of our ride at The Rum Fox, a stylish gastropub in Grindleton, 14km from Whitewell. We can especially recommend the rabbit and nduja lasagne as a starter. When not in the kitchen, chef-proprietor Bob Geldeard is usually out on his bike. Details: therumfox.com

Bowland fells

Having already had several close encounters with sheep and grouse today, I’m more than happy to heed Mal’s advice.

From Wray, the road hugs another river and starts its inexorable trajectory towards the highest point of today’s route, growing progressively narrower between overgrown verges and farm walls. Ageing, flaking signposts point to places with rugged-sounding names but I never arrive at any of them. I also bid farewell to NCN Route 69 which enhances the feeling of heading off into the great unknown.

I stop at every fork in the road to check my Garmin. The Bowland Fells stretch out around me, great shadowy expanses of rolling moorland, occasionally blazing with heather or dotted with sheep. Rising to the east is the sharp-edged, flat-topped silhouette of Langcliffe Scar, looking like a miniature Table Mountain.

A couple of horse riders are emerging from a track that disappears into the shadows of the hills and for a moment I’m transported to the vast, empty landscapes of the old Wild West.

Today is a sunny August day, but I can only imagine how bleak this place must be in winter. The Reverend Tommy Reid sometimes had to leave his bike at the vicarage and get a lift to church in a farmer’s jeep. Bradley Wiggins, meanwhile, put in some tough winter miles here before his 2012 Tour success, declaring afterwards: “The Tour was won on these roads.”

I eventually join the road that will take me over the fells via the Cross of Greet. The last kilometre is the toughest, its gradient rarely dipping below double figures, but at least it’s free of traffic. At the 426-metre summit there is no cross, just a cattle grid.

Praise be!

Below me, the road unfurls down a shallow valley towards an expanse of water and the distant Pendle Hill. I’m glad I topped up my water bottle in Wray, as this has been thirsty work.

I don’t realise it at the time but the bubbling brook to my right will follow me all the way to the finish, evolving into the full-flowing, salmon and trout-rich River Hodder.

The descent isn’t quite the carefree freewheel I’d anticipated. There are some bumps and lumps along the way and then a seriously steep, 14–kilometre-long ramp just before the village of Slaidburn.

The distraction of arriving back in civilisation is short-lived before another no-nonsense rise in the road – this time 16% – demands my full attention. Finally, the road starts descending in earnest. It’s another picture-postcard stretch, with the River Hodder and distant hills to my left and undulating pastures to my right.

Dunsop Bridge is another village straight out of the ‘Quaint Rural Places of the UK’ handbook, this one with a strange claim to fame – it’s reputedly the ‘geographical centre of Great Britain’, a fact commemorated with an inscription on the door of its phone box which in 1992 was the 100,000th payphone to be installed by BT.

The inferior, bright red sign further along the road declaring the village tearoom’s garden to be the ‘Centre of the United Kingdom’ is nothing but shameless and inaccurate clickbait.

A few miles later I’m back where I started today’s ride. I’ve followed in the footsteps of witches, looked down on Blackpool Tower, ridden through the centre of Great Britain and traced the wheel tracks of cycling heroes.

Sir Bradley Wiggins and Hugh Carthy probably wouldn’t even raise an eyebrow at my achievement. But I think the Reverend Tommy Reid, the cycling vicar of St. Michael’s, would give me his blessing.