Gary Lineker’s tweet criticising the government’s asylum policy has led many to question when – if ever – it can be helpful to compare modern events to history. The chair of the Holocaust Education Trust rushed to condemn all historical comparisons between the Holocaust and current events.

But Lineker had not mentioned the Holocaust, the systematic murder of six million European Jews between 1942 and 1945. His tweet referred to the exclusion of German Jews from German society in the 1930s, and to the role that language plays in “othering” and demonising human beings – Jews then, refugees today. But that nuance got lost in the hype.

What the hype does show is that the Holocaust still looms large as the embodiment of absolute evil. But if evil is absolute, can we learn anything from the Holocaust today?

One answer is that the Holocaust teaches us that “all hate is bad”. The universalism of this statement renders specific comparisons unnecessary, and thus avoids controversy. But like most simple answers, it creates more problems than it solves. Importantly, it risks obscuring the specificity of the hate that created the Holocaust: anti-Jewish hate.

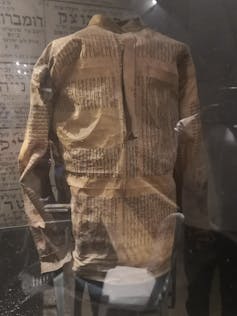

The Nazi regime and its collaborators did not just target an ethnic minority. They wanted to exterminate what they perceived as an all-powerful global enemy: world Jewry. Jews, they felt, were untrustworthy and dangerous, and not just at one moment in time – they always had been. Hatred of the Jewish religion was central to this belief. Synagogues were the prime target of Kristallnacht, the Nazis’ November pogrom of 1938. Before buildings were set on fire, Torah scrolls were removed and publicly desecrated. An SS guard at Auschwitz made himself a uniform using the scrolls. Others were used as lampshade and lining for handbags.

This manic obsession with performing symbolic violence against Judaism was integral to the psychology of mass murder. It was not just about hatred of different races. It was also about a desire to “cleanse” one’s own culture from its deep entanglement with the Jewish religion and a 2,000-year history of European-Jewish culture.

How antisemitism endures

The Holocaust may be over, but antisemitism is not. Nor did it start in 1933. When Hitler wrote Mein Kampf (My Struggle), long passages quoted a “respectable” canon of European culture, from ancient Roman authors via St Augustine to early modern and modern thinkers from across the political spectrum. The common denominator was their shared tendency to paint Jews as the villains of world history.

This tradition has not disappeared. Nor is it un-British, as can be seen in exhibitions and learning programmes at the UK’s National Holocaust Centre and Museum. To this day, a shrine to Little St Hugh in Lincoln Cathedral commemorates the “blood libel” – the false claim that Jews slaughter Christian babies to use their blood for making Passover food. England was the first country in which the crown recognised such rumours as truth.

In the following centuries, there are antisemitic tropes in the work of Shakespeare, Charles Dickens and Roald Dahl.

Anti-Jewish hate remains a staple of British school curricula and culture. Our ongoing research suggests that more than 50% of Britons subscribe to at least one conspiracy theory. And believing in one conspiracy theory is the best predictor for people believing in others, too.

So even if a conspiracy theory does not explicitly mention Jews, the common structure of conspiracy theories – that dark, invisible forces control the world – normalises the core assumption that antisemitic conspiracy theories build on. New data we will publish shortly shows that about 20% of those surveyed believe that “Jews control the media”, “Jews are materialistic and exploitative”, or “Jews disguise their true identities”.

This is where history provides useful lessons. Factually correcting conspiracy theories is rarely effective. Exposing the historical genealogy of these ideas is. Showing how antisemitic slogans and images of the present recycle an old arsenal of anti-Jewish tropes is more likely to encourage people to question longstanding, seemingly “natural” assumptions.

At the National Holocaust Centre and Museum, where I work as chief academic advisor, we have worked with a group of 30 schools to transform the secondary curriculum, and alert students to the dangers of antisemitism in many different subjects. Similarly, our recently launched “Stand up to Antisemitism on campus” programme shows that exposing the historical origins of antisemitic fantasies is highly effective in transforming attitudes and behaviours.

The power of image

Combating antisemitism is a huge challenge, and social media has become a conveyor belt for antisemitic conspiracy theories. How we teach and commemorate the Holocaust can make a real difference.

Too often, the history of the Holocaust is taught through the lens of the perpetrators. Museums, films and computer games over-rely on Nazis’ photos of the Holocaust, which were designed to denigrate and dehumanise the victims. We can contextualise them differently now. But images have psychological effects that are difficult to counter with words alone.

Our recent exhibition The Eye as Witness: Recording the Holocaust challenged this visual bias, placing Jewish photography at the heart of the story. Audience reactions, which we measured through interactive screen displays where people recorded their responses to images, show that engaging with these very different images brings forth a different historical imagination, which does not objectify Jews, and creates powerful emotional antidotes to antisemitic assumptions.

The Holocaust was made possible by a hatred of the Jewish religion and culture that is deeply embedded in our culture, and that did not end in 1945. Only if we constantly challenge antisemitism in our own heritage and identity can we truly hope to learn lessons from the Holocaust – and make meaningful comparisons with the present.

Maiken Umbach works as chief academic advisor for the UK National Holocaust Centre and Museum, and educational charity.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.jpg?w=600)