In recent years, the idea of “common sense” has again catapulted to prominence in the conservative political landscape.

From United States President Donald Trump’s call for a “revolution of common sense” and his references to himself as a “common-sense conservative” to Pierre Poilievre’s references to his party as “Common Sense Conservatives” the value of common sense has been widely trumpeted.

As a professor in climate and environmental humanities, I’m interested in examining how this return to common sense tends to focus attention away from climate action.

Common sense is the domain of the obvious, the self-evident and what goes without saying. “Hot things can burn you,” for example, is the maxim with which historian Sophia Rosenfeld opens her political history of common sense.

The history of common sense

Attaching common sense to conservative political positions in Canada is not new. The phrase revives Ontario Premier Mike Harris’s “Common Sense Revolution” in the 1990s.

Read more: Mike Harris’s 'common sense' attack on Ontario schools is back — and so are teachers' strikes

But common sense also has a longer conservative legacy. In the U.S., as American historian Larry Glickman illustrates, the phrase was deployed in the 1930s to challenge the perceived turn to social aid associated with New Deal policies. Prior to Trump, it has been used by Ronald Reagan, Sarah Palin and so-called Tea Party Republicans.

Common sense as a political strategy, however, was not always aligned with a free market economy. Rosenfeld traces its history from the Greeks and 17th-century and 18-century writers through to 20th-century thinkers like German-American philosopher Hannah Arendt.

As Rosenfeld notes, common sense has long had two contrasting emphases: an inquiry position that questions prevailing norms and a conservative position that doubles down on prevailing norms.

Democracy and common sense

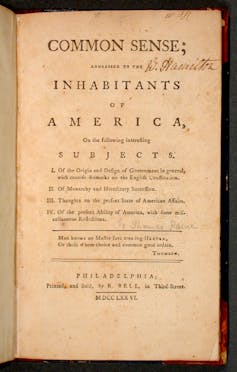

The inquiry position emerged, Rosenfeld illustrates, in the 18th century and its best-known version is a radical pamphlet, Common Sense, written by British American author and pamphleteer Thomas Paine in 1776.

This pamphlet energized readers across all political spectrums to support the principles of equality, liberty and freedom of expression that we now associate with democracy at large.

The conservative position, by contrast, emerges when these same values threatened religious belief and the free market. In this version, expertise is discounted and the people’s everyday experience is privileged.

Historically, this position has given rise to a populism that accordingly also discredits education, debate and other pillars of democratic practice. As Rosenfeld demonstrates, the history of common sense shows that common sense has been mobilized both to support democracy and to undermine it.

Common sense encompasses the world of everyday things like temperature and know-how, and it describes a deeper world that defines how we understand each other and live together in that everyday world. Its ability to toggle between these two domains is part of what gives it its force.

What ‘everyone knows’

Most of the time, common sense operates quietly because it is assumed to be tacit knowledge — what everyone knows. In times of crisis, however, common sense comes out of the shadows.

It is no surprise, then, to see common sense entering public discourse in Canada when the country is beset by multiple crises: the existential threat posed by climate change, economic inequality and racism, to name only a few. Common sense, in this context, emerges as a call to return to when things were “normal.” It is the comfort food of thinking.

For many people, there is solace in turning to what is familiar and seemingly obvious. For many others, there is not.

Read more: Canadians are losing faith in the economy — and it's affecting their perception of inequality

‘Common sense’ of market and environment

Poilievre defines himself as a “champion of a free market.”

“Free enterprise” and the market economy was also, as Glickman argues, the platform that Republicans polished into common sense. And it is, arguably, the platform that produced the very issues that most endanger us now, from climate change to economic inequality.

But, as Einstein noted: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” The common sense of the market economy, in other words, cannot solve the problems it created.

Waking up to common sense

The versatility of common sense as a populist political strategy is evident in Poilievre’s platform.

For example, he wants voters to perceive him as radical by having attacked and apparently succeeded in undermining the idea of a carbon tax in both Conservative and Liberal platforms (the revolutionary side of common sense) while doubling down on what he calls woke politics (the conservative side of common sense).

The concept of being woke, in turn, has been adopted as shorthand to criticize calls for climate action, a point reinforced in Poilievre’s recent conversation with psychologist and author Jordan Peterson when “he called people concerned about climate change ‘environmental loons that hate our energy.’”

It’s always easier to stay with the old and familiar. But we are already in unfamiliar and unavoidable terrain.

Our national parks are burning. Our air quality has been worse than any other country in the world. Flooding across the country is on the rise as is extreme heat.

Caring economy needed

Free-market common sense does not help us here. A neoliberal economy in which profits are more important than people and the planet does not help us here. What does, then?

It’s not a leap to try to create the conditions for a caring rather than an extractive economy, as the collaborative work of scholars and activists Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Robin Maynard suggests.

Hot things can burn you. The hot things we confront now are not stove tops or flames, but global temperature increases. Leaders, it seems, tend to deploy “common sense” as an excuse to look away from the hot things that matter. Common sense, in its everyday meaning, would suggest that we look at them.

Common sense works best rhetorically when it’s not questioned. The history of common sense suggests that now is the time to question it.

Barbara Leckie receives funding from SSHRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.