From having a debate on whether capital gains tax would discourage investments to bringing in various provisions in the tax book on how to levy tax in diverse scenarios, India has come a long way. This story takes a look at the history of capital gains taxation (CGT) in India for three asset classes — equity, immovable property and gold—all of which have been creating wealth for investors in the long run.

You might also like

How growth stories of India and China stack up

Big deal is what matters for Cognizant CEO Kumar

For Avenue Supermarts, muted growth or speedy recovery?

There have been several changes to the CGT of listed equity in India in the last three decades. The only thing constant though is the holding period of one year to be eligible for long-term capital gains (LTCG). Tax rules on immovable property and gold have largely been untouched.

With inputs from Dipen Mittal, a chartered accountant from Taxmann, a tax publishing company, we lay down the key events in the history of CGT starting 1991, the beginning of a decade of economic reforms in India.

The beginning

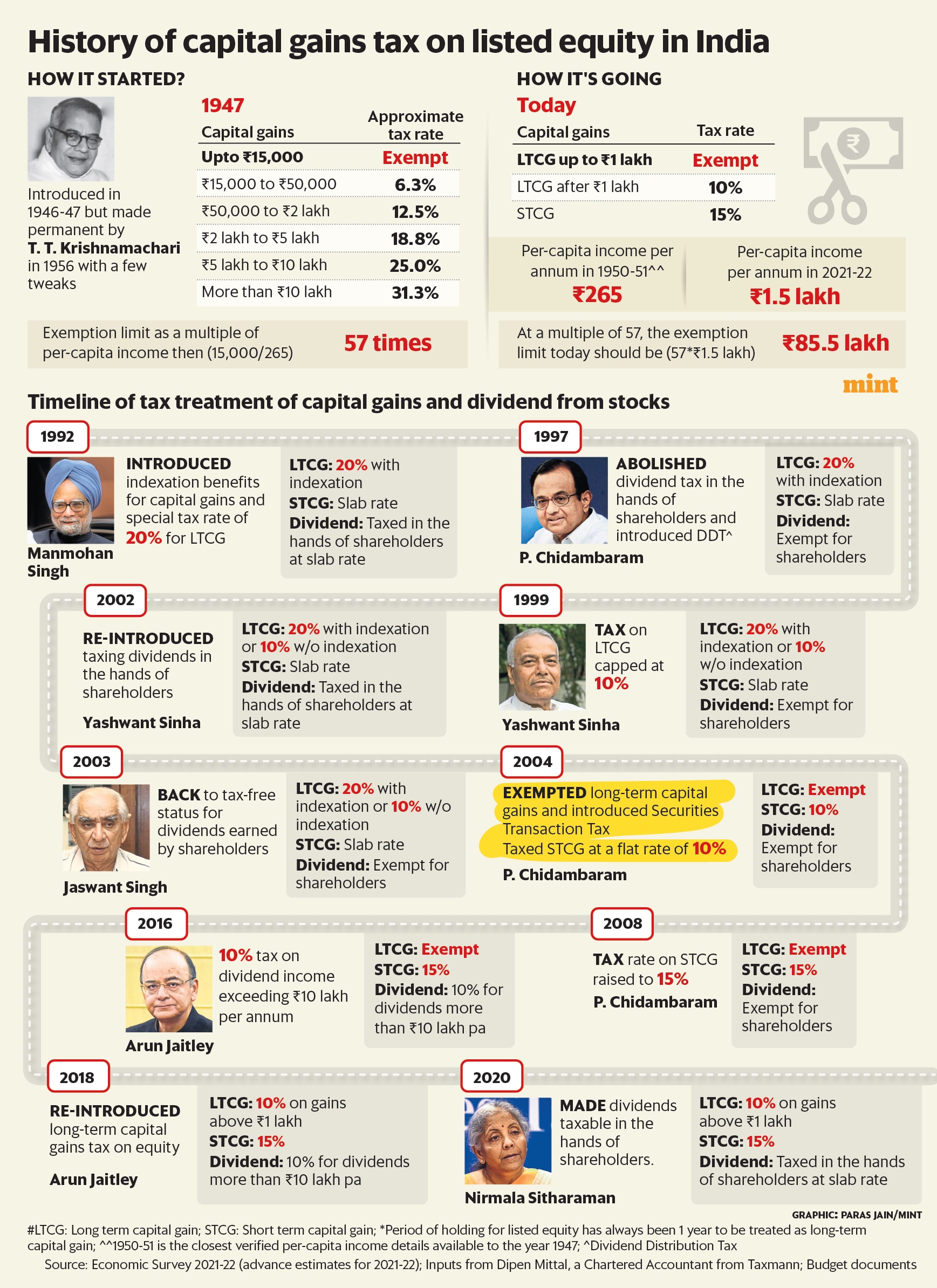

The tax on capital gains was first introduced to curb speculative activity of buying and selling assets in an inflationary environment. The earliest incidence of tax was for capital gains earned during 1 April 1946 and 31 March 1948. The government followed a progressive tax structure, exempting gains of up to ₹15,000 (see graphic). The tax was abolished in 1949 as it was believed to have hampered stocks and shares transaction.

But Union budget 1956-57 made the levy of capital gains tax permanent in India. The then finance minister, T.T. Krishnamachari, reintroduced CGT with a few tweaks to increase the tax revenue. He believed that capital gains are an important factor in aggravating economic inequalities. In his budget speech in 1956, Krishnamachari said the practice of not taxing such gains is “a lacuna, one dare say, they will have to rectify in due course. For a developing economy like ours, it is necessary to take early action…."

1992: Acknowledging inflation

Fast forward to 1991, capital gains (sale value after subtracting the cost of acquisition) on all three asset classes— equity, immovable property and gold—were taxed at the individual’s applicable slab rates.

But that tax system was criticized since the deduction allowed in computing gains did not take into account the inflation over time.

The then finance minister, Manmohan Singh, in budget 1992, accepted the Chelliah Committee’s proposal to introduce a system of indexation—that inflates the costs in proportion to the inflation in the economy—for assets held for long term.

Since then, for LTCG, the cost of acquisition and cost of improvement of assets are linked to a cost inflation index which is notified by the government every year. The 1992 Union budget also introduced a special provision for LTCG that levies 20% tax (with indexation) applicable from April 1993.

The period of holding to be eligible for LTCG was 1 year for stocks and 3 years for immovable property and gold.

Subsequently in 1999, former finance minister Yashwant Sinha capped the tax on LTCG at 10% for stocks. Thus, a taxpayer was given a choice of being taxed LTCG on assets at 20% with indexation or at 10% without indexation benefit.

2004: LTCG exempt

In a landmark decision in 2004, then finance minister P. Chidambaram abolished the tax on LTCG on the sale of listed shares and introduced the securities transaction tax (STT), a small tax levied on the value of purchase and sale of securities. The exemption of LTCG from tax can be considered as one of the important factors in deepening the equity markets in India.

From 2004 until the LTCG tax on equity was reintroduced in 2018, the number of demat accounts in India increased manifold: from 66.7 lakh to 3.4 crore.

Santosh Joseph, a mutual fund distributor based out of Bengaluru, opines that the exemption of tax made investors look at equity as an asset class favourably. He said the exemption served as an immediate comparison of fixed deposit (FD) income and equity gains. “While the FD interest was taxable with applicability of TDS (tax deducted at source), equity gains including dividend was exempt from tax for a long period, which moved the needle in favour of equity," Joseph added.

Vishal Dhawan, a registered investment advisor, said that exemption was only one of the factors that drove investors to the equity markets.

Nevertheless, those who invested in Indian equity from 2004 till the tax was subsequently reintroduced in 2018 would have generated absolute tax-free return of about 540% (sensex returns) from capital appreciation, thanks to the LTCG exempt status, which is unlikely to happen again.

Chidambaram, in the budget presented in 2004, also reduced the rate of tax on short-term capital gains on listed equity to a flat rate of 10% (from taxing at slab rate), but raised this to 15% in budget 2008.

2018: End of an era

Former finance minister Arun Jaitley decided in 2018 to end the exemption that investors enjoyed on LTCG on shares for almost 14 years. Since then, LTCG exceeding ₹1 lakh are being taxed at the rate of 10% without any indexation. However, all gains up to 31 January 2018 was grandfathered, which means gains made until such date are exempt from tax.

The STT tax, which was introduced in lieu of LTCG tax, continues.

Tax on dividend income

In 1997, Chidambaram announced abolition of taxing dividends in the hands of shareholders (at slab rate) and introduced dividend distribution tax (DDT), which levy tax on corporates. This was considered a radical change in the history of dividends taxation in India.

The introduction of DDT brought along with it the debate of applying dividend distribution tax rate, which otherwise is exempt or attracts a lower tax rate for those in the bottom of the pyramid in the tax structure; the DDT rate was higher than the bottom tax rates and lower than the highest tax rates applicable to an investor.

The debate continued for years. In 2016, Jaitley found a middle ground and introduced tax of 10% on individuals receiving dividend in excess of ₹10 lakh per annum, while retaining DDT. This was aimed at preventing persons in the high-income groups paying tax at much lower rates on dividend.

But this measure was in existence only till finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman reintroduced the classical system of taxing dividends entirely in the hands of shareholders, in her second budget speech in 2020. This also put an end to the DDT in India.

What 2023 holds

The tax rules on immovable property and gold have largely been untouched since 1992. For both these assets, the LTCG (in case of assets held for more than 36 months) and STCG are taxed at 20% with indexation benefit and at individual income tax slab rate respectively.

However, the holding period for the applicability of LTCG in case of an immovable property was reduced from 36 months to 24 months in budget 2017.

In the case of equity, the reintroduction of capital gains tax in 2018 hasn’t had any impact on the retail investors participation in stock market transactions. The Indian investors quickly accepted the changes in the CGT on equity. It is emerging as one of the preferred asset classes for most investors because of its ability to generate inflation-beating returns in the long-run.

Going ahead, budget 2023 is expected to tweak capital gains tax regime for various assets both in terms of holding period and tax rates. We need to wait and see if 2023 can leave its mark in the history of CGT in India.

Elsewhere in Mint

In Opinion, Madan Sabnavis says the upcoming budget may not spring any big surprise. Pramit Bhattacharya reveals what data says about the great Indian middle class. Rajat Dhawan writes about five priorities for India Inc. Long Story delves deep into India's ongoing pension battle.