Unfortunately, there are certain cuisines that don't have the same cultural cache, if you will, that others — like Italian, Thai, Chinese and Mexican — have developed in the United States.

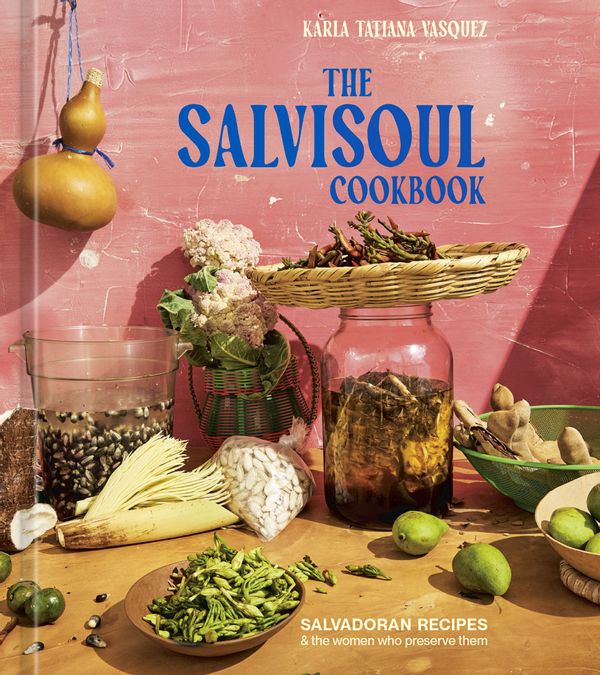

One of these unsung heroes of the culinary space is El Salvador, and Karla Tatiana Vasquez has made it her mission to celebrate the country, the cuisine, and in particular, the women who forged ahead, ideating brilliant dishes and highlighting the best ingredients from their land.

Vasquez credits her grandmother with giving her the idea to look deeper into their collective history and heritage, which brought SalviSoul — and Vasquez's new cookbook of the same name— to life. It's a particularly notable accomplishment because "SalviSoul" is the first Salvadoran cookbook to ever be released by a major American publishing house.

"Historically, women's labor has always been ignored and by proxy they become invisible, this has been even more true for Salvadoran women as we are often erased due to being women of color and immigrants," Vasquez said.

Salon Food spoke with Vasquez about the history and tradition of Salvadoran culinary customs and how important it is to continue to honor those efforts — and enjoy some really delicious food while you're at it, too

For those unfamiliar with Salvadoran food, how would you explain its fundamentals, tenets, core ingredients and focuses?

A part of the cuisine that often gets me excited is how many edible blossoms and flower buds there are to consume. Just in the diaspora, we have access to about three: Flor de Izote, Flor de Loroco, and Flor de Pacaya. There are more than that, but these are the most easily accessible to us living away from El Salvador.

Then, there are of course a love for corn, beans, ayote (squash) and chiles: These Mesoamerican ingredients are part of the building blocks of Salvadoran cooking, but also there are tropical flavors like plantain, mangos, pineapple. Finally, there's an appreciation to a lot of tart, sour and funky flavors. We see this in Salvadoran cheeses, the many curtidos, and fruits we consume.

I love the subtitle “Salvadoran Recipes and the women who preserve them.” Obviously, you go in-depth about that in the book, but how would you sum up that notion for our readers?

SalviSoul is all about giving credit where credit is due. There has not been a place, or book yet that acknowledges the labor of Salvadoran women cooks who are largely responsible for bringing this cuisine to this country. Historically, women's labor has always been ignored and by proxy they become invisible, this has been even more true for Salvadoran women as we are often erased due to being women of color and immigrants.

Making that the subtitle was honest to my personal journey with this work but also an effort to show them love, care, tenderness and respect.

Can you explain a bit about SalviSoul? What led to its founding?

SalviSoul started in 2015 with my grandmother, Mama Lucy. Back then, I had a craving for Salpicon — a meat salad — but I did not possess the skills to make it, so I reached out to my grandmother. As she taught me the recipe, she shared some of her stories and that time laid the groundwork for what SalviSoul is now.

Recipes and stories are equal amounts of nourishment, especially for someone like me, who wanted to know more about what El Salvador was like. I felt the most connected to what it meant to be Salvadoran when I was surrounded with Salvadoran food and family.

This work also started because even though there are more than 2 million Salvadorans in the country and we've been in the country since the late 1970s, a major publisher had still not published a cookbook on the cuisine. I'm fortunate that I've had a lot of crystal clarity about what SalviSoul is here to do, and that's carve a place for it to exist in mainstream culture through a cookbook so that anyone that wants it, Salvadoran or not, can access it.

How important — as well as necessary and overdue — is that representation?

It's important because there are so many Salvadorans in the diaspora and so many of us have a transnational identity. We live in one place, but are very much sincerely connected to a homeland, and for a lot of us, practicing our foodways is a way to keep that connection alive.

I'm so happy this book exists for those that are looking for it. When I started this project, I would have loved to have come across a book like this. I didn't think I would have to make it happen myself, but now that it's here, I'm so happy for the community that wants this because they'll be able to access it.

Do you have a favorite recipe in the book? Conversely, what would you say is an ideal “gateway” recipe in the book for someone who’s never cooked or eaten Salvadoran food before?

One hundred percent it would be Rellenos de Güisquil. They are my absolute favorite and it's one of those great home made dishes. You don't usually find this dish in restaurants, so if you're curious about what Salvadoran families ate on a weekday, this would be it.

What stands out for you as a formative moment that got you into cooking or food at large?

My experience as a food justice organizer was crucial to my formation as a cookbook author. Food is such an enormous presence in our lives, but so many of us don't really know what or how it's made, harvested, cared for, etc.

Working with farmers [and] championing programs that benefited WIC and Cal Fresh participants were all incredible important to the work I do now even. I've been in food for about 12 years, as a culinary producer, food stylist, [and] food writer, but my experience as a food justice organizer were much more formative for me when we talk about life and meaning.

The others felt like professional stops along the way, but with organizing, everything changed for me.

What was the development process of the book like?

This process has been 8-plus years. It's taken very long to get here. So much of it felt like kismet and fate collaborating with me to see what this project [or] book wanted to be.

First, I interviewed my grandmother, then more family and family friends, and then a callout in 2017 helped me find the rest of the women. Then, through a collaborative process, we curated what would be in the book.

The stories I share in the book are their stories [from] when we cooked [and] these memories would pop up. It took so much time because the industry wasn't ready to get behind it when I started pitching. Then, part of it was also [that] it's been my emotional journey in real time. The Karla who started this is not the same to now. My grandmother passed throughout the process, so it became a way to process my own grief and a myriad of other things.

The book contains 30-plus accounts from Salvadoran women, discussing everything from the idea of the American dream to the food and Salvadoran culture at large. That link from El Salvador to wherever some of them now reside in the US is so strong. How do most of them strive towards preserving those foodways?

Most of them do the best they can to remember and practice what they can. I think most of them do so because all of us have a longing for home or the familiar so even if they don't set out to "preserve foodways," food is how we can touch home sometimes.

For a lot of us who aren't able to go back, don't have the means to go back, or maybe Spanish isn't something we have to help us feel connected, food can be that bridge.

I love how the recipes connect to the stories from the particular women throughout the book; are there any specific examples that stand out most for you or best exemplify the ethos of SalviSoul?

The best part of having the book done is that any way you slice the book, you will get an example that exemplifies the ethos of SalviSoul. The whole book is about that question. Each recipe and story illustrates the heart and soul of the culture and people.

Can you explain the meaning behind "Donde come uno, comen dos is a dicho?"

I love this dicho/saying because in all of my interviews with the Salvadoran women in the book, this saying came up. The saying literally translates to "where one can eat, two can eat."

Without fault, whenever they shared stories where they encountered hard times, when there wasn't enough food, or food was scarce, they would finish their story with this saying. It became another way to describe radical community care, Salvadoran hospitality and women taking care of their loved ones.