The arrest of Tunisia’s leading opposition figure, Rached Ghannouchi, is a bleak moment. Profound disenchantment has been widespread for years domestically, as democratic reforms hit a wall, corruption remained entrenched and the economic picture deteriorated. Nonetheless, the country was an important if imperfect symbol of freedom: not only the birthplace of the Arab spring, but seemingly its sole success story. Tunisia moved from Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali’s autocratic rule to democracy with a thriving civil society and lively media, while others descended into anarchy, bloodshed and brutal repression. The ascent of Ennahda, which transitioned from Islamist movement to mainstream political party, stood as proof that violent extremism was not the only way to challenge authoritarian rule.

But Tunisia failed to embed democracy with the rule of law – for example, failing to establish a supreme court. Widespread discontent at the state of the country helped to sweep outsider Kais Saied, a conservative law scholar, to victory in 2019 elections. Supporters hoped he would tackle corruption, deal with entrenched problems and kickstart the economy. Even when he suspended parliament in 2021, ousted the prime minister, took on judicial powers and imposed emergency law, he enjoyed significant backing.

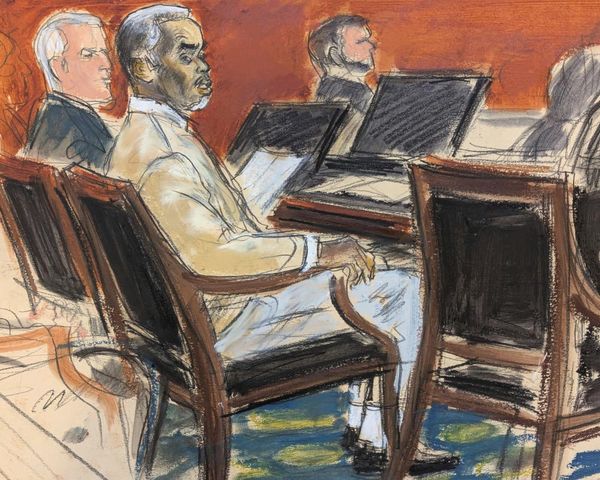

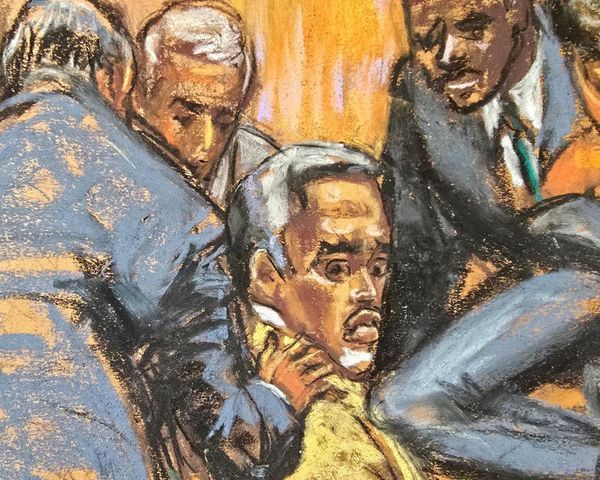

This year, he embarked upon a roundup of politicians, trade unionists, business people, judges and media figures that Amnesty International described as a politically motivated witch-hunt. On Monday, scores of police arrested Mr Ghannouchi, leader of Ennahda who was elected speaker of the parliament, seizing on his remark that “Tunisia without Ennahda, without political Islam, without the left or any other component is a project for civil war”. On Thursday he was jailed ahead of a trial for plotting against state security, a charge that, in theory at least, can carry the death penalty. Ennahda officials fear the party will shortly be banned.

Mr Saied’s sinister rhetoric has included calling opponents “a cancer” to be “cured with chemicals”. He believes, or wants Tunisians to believe, that the nation faces a grand conspiracy involving everyone from secular leftists and Islamists to the French intellectual Bernard Henri-Lévy. It is not hard to see why some have dubbed him “Gaddafi without petrol”. Migrants, refugees and black Tunisians faced brutal attacks after he promoted a Tunisian version of the racist, far-right “great replacement theory”. Some fear the potential for wider bloodshed.

For the politically active, the price of opposition grows by the day. Ordinary Tunisians are uninspired by political alternatives and appear to see little point in taking to the streets: this is where revolution got them. And western countries have opted for short-term stability and support in reducing migration to Europe, failing to acknowledge – still less act on – the rapidly deteriorating political and human rights situation. Extraordinarily, though December’s parliamentary elections saw the second-lowest turnout recorded worldwide since 1945 – about 11% – the US state department described them as an “essential initial step toward restoring the country’s democratic trajectory”.

The US and others are finally toughening their language. Better late than never. They must now concentrate on leverage. Mr Saied has also endangered the International Monetary Fund loan that Tunisia desperately needs. Repression is no more likely to serve his people than it did under Mr Ben Ali’s rule.

• This article was amended on 20 April 2023. An earlier version said that the leader of Ennahda, Rached Ghannouchi, was a former prime minister. In fact, he was the speaker of Tunisia’s parliament.