“People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones” is a phrase that must be ringing in the ears of Tory party campaigners. They were caught spreading election disinformation against Labour’s London mayor on the day that Conservative ministers accused Chinese hackers of meddling in democracy by targeting Beijing’s opponents in the UK.

The Conservative party did delete footage of a panicked crowd at a New York subway station, which it used to falsely state that London had become a “crime capital of the world”, after online criticism. But the rest of the video, with its spurious claims, remained up on Tuesday evening.

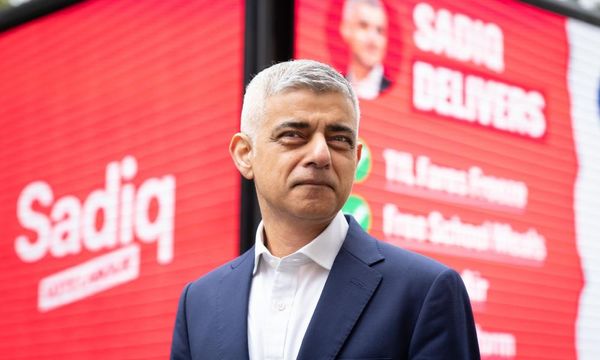

Sadiq Khan, who is standing for re-election for a third term as London mayor this May, rightly condemned the Tory video as lies and misinformation. The Conservative party is resorting to underhand tactics and fake news because it has an uninspiring candidate, Susan Hall, in London and is far behind in the polls. In January, the Tories posted an attack video on social media that misrepresented comments by Mr Khan to make it look as if he was proud to be antisemitic. The Conservative party shamefully refused to take it down.

It would be easy to dismiss the campaign advert as simply ludicrous. But it is also dangerous in its embrace of conspiracy-minded tropes, some of which are popular among the far right. It claims that masked Ulez enforcers, represented by a shadowy figure in a dark alleyway, are “terrorising communities”, and that the Ulez policy is “forcing people to stay inside or go underground”.

Mr Khan lives under 24-hour police protection. But the threat from disinformation is not only to him. The mayor warned that AI-generated audio which purported to capture him making incendiary remarks about Remembrance weekend last year almost caused serious disorder after it was widely shared by the far right. Fake news can – thanks to social media – spread as never before. This makes it far more dangerous. Political deepfakes, if left unchallenged, could have profound implications for journalism, voter ethics, and the quality of democracy.

Perhaps the Tories hope that many will share their fake videos because, even though voters know the content is false, the stories stir up resentment. The Tory party has long seeded these clouds. Mr Khan is England’s most high-profile Muslim politician, but he has not been defined by his faith. This has not stopped his opponent, who has falsely told fellow Tories that Jewish Londoners were frightened of Mr Khan’s “divisive attitude”. An investigation into Ms Hall’s social media posts found she had repeatedly endorsed racially charged abuse of Labour’s mayor.

The Tory party has also attempted to create more favourable terms for itself in London, a Labour stronghold, by changing from a preferential voting system to first past the post. This was a step back for electoral reform, but combined with voter ID requirements, it made Mr Khan’s return to office harder. But so does his incumbency.

The social costs of virally spreading false information are real. In Europe, the posting of anti-refugee sentiment on Facebook has been correlated with violent attacks on refugees. Voters are also worse off when they believe false statements because disinformation has made it almost impossible for them to choose high-quality candidates. If we want a democratic society with policies that respond to evidence, then we must pay attention to the changing character of propaganda and develop suitable responses.

• This article was amended on 27 March 2024. An earlier version referred to “a proportional voting system” where “a preferential voting system” was meant.