The Albanese government proposes to ditch the “Yes/No” case pamphlets that are ordinarily posted to voters before a referendum. Is this a good idea, and what, if anything, should replace it?

What changes are proposed?

Under the existing law, after a proposed constitutional amendment is passed by parliament, a majority of MPs who voted for it may prepare a written Yes case of up to 2,000 words. If any members voted against it in parliament, they can prepare the official No case.

Before the referendum, the electoral commissioner sends a pamphlet in the mail to every voter. This includes the Yes case and the No case (if one has been provided) as well as a copy of the proposed changes to be made to the Constitution. This is the only official information given to voters to help them decide how to vote in the referendum.

The Commonwealth government is currently prohibited from otherwise spending money on the presentation of arguments for or against a referendum proposal.

In its Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Amendment Bill 2022, the Albanese government intends to “disapply” the relevant section so it ceases to operate until the next general election. The effect would be that there would be no official Yes/No case distributed to voters for any referendum held in this term of parliament, and no legal restriction on government spending on the referendum campaign.

Read more: Creating a constitutional Voice – the words that could change Australia

What is the point of the Yes/No case?

The Yes/No case pamphlet was first required by a law enacted in 1912. It was introduced due to a concern that the previous referendum had failed because the voters were inadequately informed.

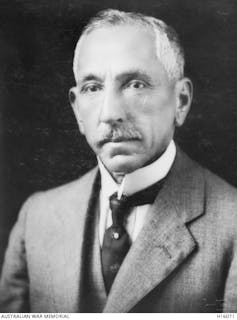

Opposition Leader Alfred Deakin, who had opposed the previous referendum, was nonetheless supportive of introducing better public education on referendums. He argued:

It is our duty, when we ask the electors to vote for or against momentous proposals of this kind, to give them the best material we have in order that they may form an independent judgment.

The attorney-general of the day, Billy Hughes, had a rather naïve expectation of how the Yes/No case would be used. He said:

Honourable Members may put their case before the public, provided that it is put in an impersonal, reasonable, and judicial way. There is to be no imputation of motives. In short, the argument is to be one which appeals to the reason rather than to the emotions and party sentiments.

This is not how things have turned out. In fact, the Yes/No case, because it is prepared by political partisans, is often misleading and emotive, particularly on the No side.

The No case and the aviation referendum

A good example is the 1937 referendum on giving the Commonwealth parliament power to legislate on aviation. When the Constitution was first being written, the Wright brothers had not yet flown a plane. So there was nothing in it about making laws to govern aviation in Australia.

The consequence was that federal laws applied to flights in and out of Australia and some interstate flights, but not to planes flying within a state. This was inefficient and potentially dangerous, so a referendum was held to give the Commonwealth full power over aviation in 1937. Despite it logically being the type of thing that should be dealt with on a national basis, the referendum was lost.

The No case had argued the expansion of aviation would compete with and ruin the state railway systems. It would make railway workers unemployed and bankrupt country towns. The price of food would sky-rocket, because the cost of freight would be higher and the finances of every state government would be endangered.

These claims were highly exaggerated and had nothing to do with whether the Commonwealth or the states should regulate aviation. But it was enough to make some people worried and so vote No.

It is, of course, difficult to attribute referendum outcomes to the inflammatory and misleading content of the Yes/No cases, as most people don’t read them. But some will, and the official nature of the document will give its contents greater credence than they deserve.

Read more: Changing the Australian Constitution is not easy. But we need to stop thinking it's impossible

Referendum pamphlets in New South Wales

In contrast, in New South Wales the practice has been to have public servants, not politicians, write the pamphlet that is sent to voters prior to a referendum. The public servants are required to do so in a factually accurate and impartial manner. Before publishing the pamphlet, they send it to acknowledged experts for vetting to ensure it is accurate and a fair explanation of the issues.

The success rate of New South Wales referendums is much higher than that at the Commonwealth level. If you count state-wide referendums to amend the New South Wales Constitution where voters were given a binary Yes/No choice, then the success rate is 85%. This can be compared with the Commonwealth success rate of 18%. While other factors will also have been in play, providing voters with informative and accurate material rather than inflammatory and misleading material is likely to have helped at the state level.

What replaces the Yes/No case?

While the Yes/No case in its current form has not proved the reasonable and informative tool that was intended by Hughes, a question remains as to what should replace it. If there is no officially sanctioned information, then this just leaves open a free-for-all on social media with even more misleading material circulating. There surely needs to be at least one source of authoritative information to which people can turn.

The government has said it proposes to fund educational campaigns to promote voters’ understanding of referendums and the referendum proposal. Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus has stated the bill will “enable funding of educational initiatives to counter misinformation”.

The difficulty facing the government will be working out how this can be done in a way that maintains public confidence and is not seen to be partisan in nature.

The intention behind this change is a worthy one. The Yes/No case has long been recognised as a failed experiment. But the successful execution of the government’s educative proposals will be difficult and need great care.

Anne Twomey has received funding from the Australian Research Council and been a consultant to Parliaments, Governments and inter-governmental bodies. She is a director of Constitution Education Fund Australia (CEFA) which engages in constitutional education initiatives. It is possible that CEFA or its materials might be used in any education campaign. Anne Twomey also has her own constitutional education YouTube channel, Constitutional Clarion.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.