Launched in 1973, Project Tiger introduced India’s Tiger Reserves – which have since rapidly ascended in status. From an administrative category arbitrarily constituted and administered by the forest bureaucracy, Tiger Reserves became a statutory category in 2006. Today, Tiger Reserves are hailed worldwide as India’s miraculous success story in environment and forest conservation, especially in this age of climate change.

From only nine Reserves in 1973 encompassing 9,115 sq. km, there are 54 in 18 States, occupying 78,135.956 sq. km, or 2.38% of India’s total land area. Critical Tiger Habitats (CTH) cover 42,913.37 sq. km, or 26% of the area under National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries.

The first tiger census, in 1972, used the unreliable pug-mark method to count 1,827 tigers. As of 2022, the more reliable camera-trap method indicated there were 3,167-3,925. India’s tiger population is growing at 6.1% a year, prompting the government to claim India is now home to three-quarters of the world’s tigers.

In the same year – 1972 – India enacted the Wildlife (Protection) Act (WLPA). It introduced new spatial fixtures within notified forests, called ‘National Parks’, where the rights of forest-dwellers were removed and vested with the State government. It also created ‘Wildlife Sanctuaries’, where only some permitted rights could be exercised.

Project Tiger was the result of this development. Until then, it had been a Centrally Sponsored Scheme of the (then) Union Ministry of Environment and Forests. The government created the ‘Critical Tiger Habitat’ to vouchsafe a part of India’s forests for tiger-centric agendas. Beyond each CTH would be a Buffer Area: a mix of forest and non-forest land. But even though the latter had an inclusive, people-oriented agenda, the overall ‘fortress conservation’ approach to protecting tigers displaced people who had coexisted with tigers for generations, and became ground zero for generations of conflict.

The September 2006 amendment

In 2005, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh appointed a five-member ‘Tiger Task Force’ in 2005. He was responding to a public outcry: that India’s tigers existed only on paper and not in the forests of Sariska in Rajasthan, where the government had spent Rs 2 crore per tiger in 2002-2003 for their upkeep and safety, versus Rs 24 lakh per tiger elsewhere.

The Task Force found the approach (then) of using guns, guards, and fences wasn’t protecting tigers, and that the increasing conflict between the forest/wildlife bureaucracy and those who coexist with the tigers was a recipe for disaster. The group asserted “the protection of the tiger is inseparable from the protection of the forests it roams in. But the protection of these forests is itself inseparable from the fortunes of the people who, in India, inhabit forest areas.”

So the Parliament amended WLPA in September 2006 to create the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) and a tiger conservation plan. However, the CTH remained inviolate; the Act modified forest-dwellers’ use of the forest – mostly tribals – and planned to relocate them if required.

The amendment also didn’t prohibit the diversion of a “tiger’s forest” for development projects, and allowed wildlife to be killed as a last resort if they threatened human lives.

Four months later, the government also enacted the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006 – a.k.a. FRA. FRA recognised all customary and traditional forest rights – individual as well as community – on all forest land, including in Tiger Reserves. Under the Act, the habitation-level Gram Sabha was to democratically determine and demarcate the forest rights that FRA recognised and vested in them. The Gram Sabhas became the authority to protect, conserve, and manage the forest, wildlife, and biodiversity within their customary and traditional boundaries. As a result, FRA secured the livelihoods of at least 20 crore Indians – about half of them tribals – in 1.79 lakh villages.

Importantly, FRA introduced a ‘Critical Wildlife Habitat’ (CWH), akin to the CTH under WLPA, with one difference: once a CWH had been notified, it couldn’t be diverted for non-forestry purposes. The Adivasi movements had demanded this clause during negotiations.

The extent of CTHs

The Union Environment Ministry estimated that, under FRA, 4 crore ha of forest land was to be transferred to village-level institutions, and all forest related laws were to be fine modified accordingly.

The government planned to notify the FRA Rules on January 1, 2009, and operationalise the Act. But on November 16, 2007, the NTCA passed an order that gave the Chief Wildlife Wardens 13 days’ time to submit a proposal to delineate CTHs, each with an area of 800-1,000 sq. km. As a result of the hurry, the government ended up notifying 26 Tiger Reserves in 12 States Section 38(V) of WLPA, and without complying with its provisions.

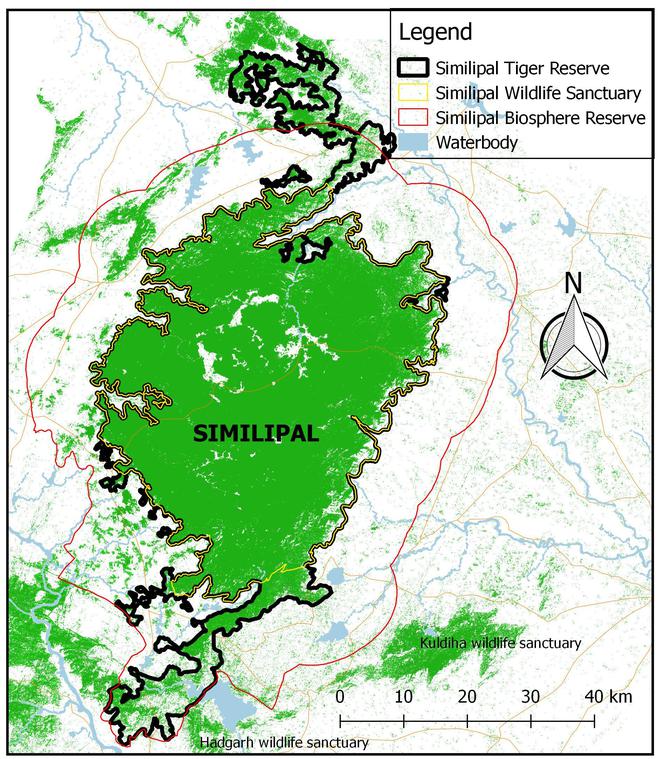

Of the 25,548.54 sq. km thus notified, 23,444.93 sq. km – or 91.77% – encompassed CTHs. And except for Similipal in Odisha, the CTHs had no Buffer Area. (They were finally added in 2012 after the Supreme Court rapped the NTCA and set it a three-month deadline.)

Today, India bears the long-term brunt of this error: tigers have been forced to inhabit and inherit a landscape heaped with illegalities.

India’s basis for CTHs

Originally, Tiger Reserves were to be created in a democratic process, “on the basis of scientific and objective criteria” and without any arbitrariness. The tiger conservation plan was similarly required to “ensure the agricultural, livelihood, development and other interests of the people living in tiger-bearing forests or a tiger reserve.”

The basis for the CTH is scientific evidence of the irreversible damage to wildlife that human activities wreak. With this in mind, the Indian government has a responsibility to ascertain whether a reasonable coexistence of forest-dwellers and tigers is possible. If not, it should modify the forest-dwellers’ rights accordingly and relocate them if necessary. (This has to be done in consultation with ecological and social scientists familiar with the area as well as the consent of the affected forest-dwellers).

Only then can a CTH be established without affecting “the rights of the Scheduled Tribes or such other forest dwellers”.

Similarly, the Buffer Area outside the CTH is to promote human-animal coexistence while recognising the livelihood, developmental, social, and cultural rights of the local people. Its geographical limits are to be determined on the basis of objective criteria with inputs from the concerned Gram Sabha as well as an expert committee.

The problem is that all of India’s Tiger Reserves have been notified without meeting these requirements. The government hasn’t obtained informed consent from forest-dwelling Scheduled Tribe communities and other traditional communities. The result: both tigers and forest-dwellers have been trapped in a tough spot, conducive to the creation of conflict.

Relocation and rehabilitation

WLPA prohibits all relocation except “voluntary relocation on mutually agreed terms and conditions” satisfying requirements in the law. Once FRA recognises people’s rights under FRA, the State acquires those rights according to the terms of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (LARR) Act 2013. No relocation can happen without the consent of the affected communities. LARR also requires the rehabilitation package to provide financial compensation as well as secure livelihoods to those relocated.

Next, under LARR, the government needs to compensate the relocated people to the extent of including twice the market value of the land, the value of assets attached to the land including trees and plants, a subsistence allowance for a year, a one-time financial assistance for relocation, building materials, belongings, and cattle, and a one-time resettlement allowance. Each family is to be provided land and a house.

The resettlement plan also includes the provision of alternative fuel, fodder, and non-timber forest produce resources on non-forest land, electric connections, roads, drainage and sanitation, safe drinking water, water for cattle, grazing land, ration shops, panchayat buildings, post offices, a seed-cum-fertiliser storage facility, basic irrigation, burial or cremation ground, an anganwadi, a school, a health centre, veterinary service centres, community centre, places of worship, and separate land for traditional tribal institutions.

However, the Union Environment Ministry and State governments have limited themselves to provisions in the 2008 Revised Guidelines for the Ongoing Centrally Sponsored Scheme of Project Tiger 2008 and subsequent guidelines. This means a compensation of Rs 10 lakh, revised in April 2021 to Rs 15 lakh, as a cash or relocation/rehabilitation ‘package’. This is not a substitute for the total compensation, resettlement, and relocation as required by the law. The remainder has been made the responsibility of State governments.

Officials have also been known to obtain signatures from the affected families under statements that they have opted to relocate. This is the bare minimum level of consent required by law.

As of 2018, there were 2,808 villages in CTHs. The Union Environment Ministry stated in the Lok Sabha that as on July 12, 2019, there were 57,386 families in these CTHs, of which 42,398 remained inside 50 Tiger Reserves.

Pitting tigers versus people

Tiger Reserves experience the most resistance to the recognition of forest rights and the rights of forest dwellers.

For example, in March 2017, NTCA barred the recognition of rights under FRA in the CTHs “in the absence of guidelines for notification of critical wildlife habitat” under FRA, which the Union Environment Ministry was to issue. Both WLPA and FRA require forest-dwellers’ rights to be recognised even inside CTHs. The Union Environment Ministry issued the guidelines in January 2018 and NTCA withdrew the ban order two months later.

FRA provides for the establishment of 13 basic government public utilities (as stated earlier). Each of these can involve felling up to 75 trees over forest land smaller than one hectare. The Gram Sabha’s consent is mandatory for such diversion of land. But on October 28, 2020, the Union Environment Ministry insisted that the National Board for Wildlife, a statutory body under WLPA, must issue a wildlife clearance if these diversions are from National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries.

However, in the law, a wildlife clearance itself is required only for projects that require environmental clearance under the Environment (Protection) Act 1986. Similarly, environmental clearances are required for 39 large industrial and infrastructure, none of which these public utilities are.

With further increase in tigers and Tiger Reserves, and tiger corridors to link them up, India’s tiger terrain is set to become a hotspot not for biodiversity but anxiety and conflict.

C.R. Bijoy examines natural resource conflicts and governance issues.

- The first tiger census, in 1972, used the unreliable pug-mark method to count 1,827 tigers.

- The government created the ‘Critical Tiger Habitat’ to vouchsafe a part of India’s forests for tiger-centric agendas.

- The Union Environment Ministry estimated that, under FRA, 4 crore ha of forest land was to be transferred to village-level institutions, and all forest related laws were to be fine modified accordingly.