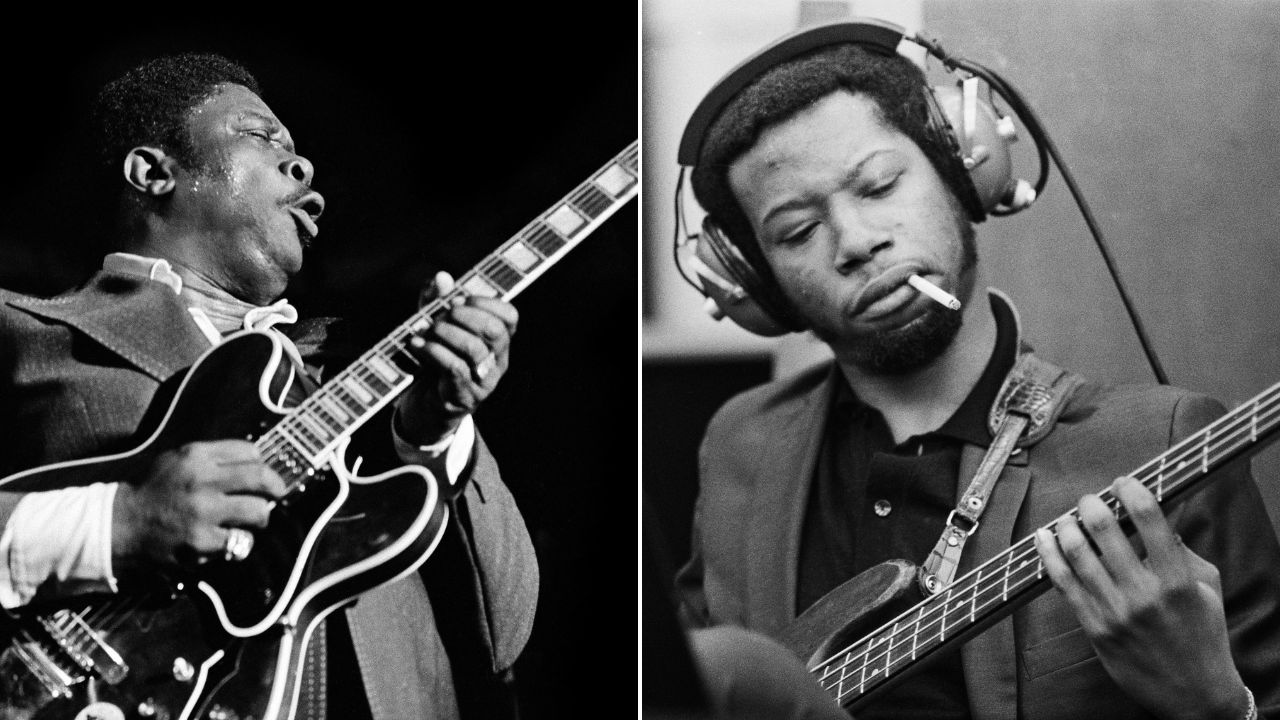

B.B. King was already a 20-year veteran bluesman when he began to seep into mainstream America's consciousness during the late '60s, via the praise of rock guitarists like Eric Clapton and Mike Bloomfield and an opening spot on a 1969 Rolling Stones tour.

At MCA, King's label, a young producer named Bill Szymczyk approached King about recording with New York session musicians. A somewhat reluctant B.B. agreed to do half an album with the studio crew and half live (at the Village Gate) with his band. The result was the now-classic Live and Well.

The session portion went so well, in fact, that a few months later, in September 1969, the group reconvened to record the epic LP Completely Well. The nine-track platter was not only King's breakthrough album, it launched the modern blues era largely on the strength of a crossover smash called The Thrill Is Gone.

Just who was this dream team, and what was their hit-making formula? Szymczyk's first call was to veteran session drummer/contractor Herb Lovelle, who reached out to guitarist Hugh McCracken, keyboardist Paul Harris, and a young bassist named Jerry Jemmott.

Jemmott had cracked the lofty studio scene a year earlier when he saved the session for Aretha Franklin’s Think by coming up with a funky bassline that brought the track together.

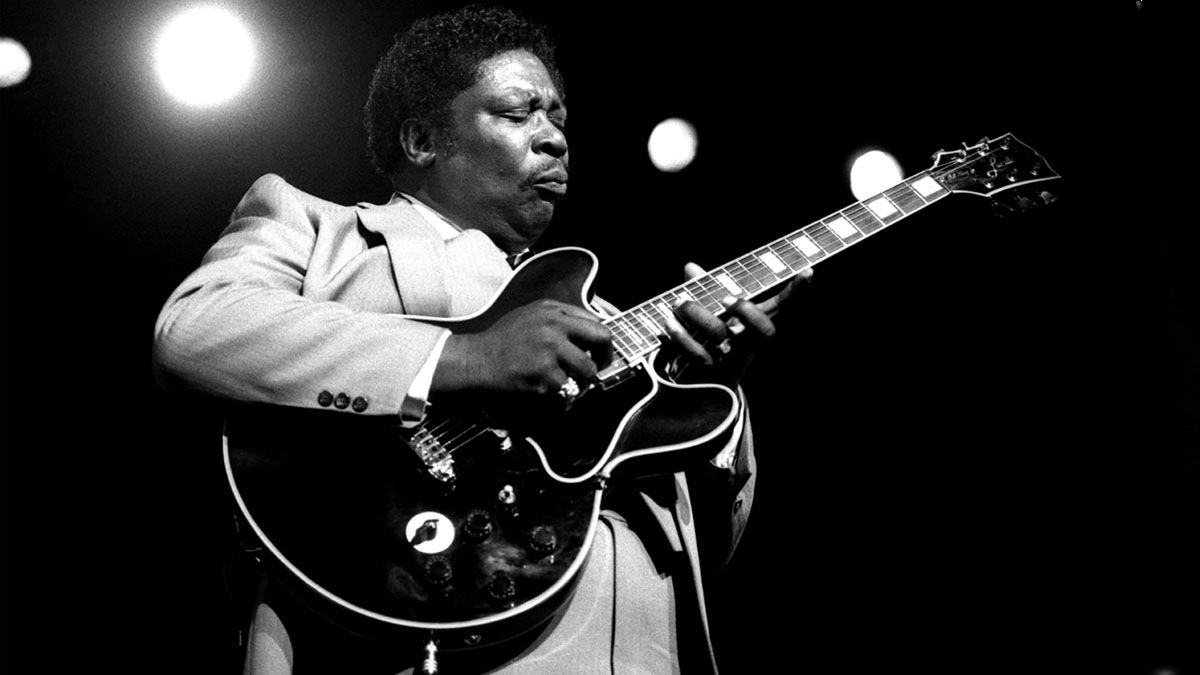

“The goal was to shake up B.B.'s music and make it chart-friendly,” Jemmott told Bass Player. “The first thing we did was turn all of his shuffle tunes into straight-eighth R&B, pop, or rock feels. The key song was Why I Sing the Blues (a hit from Live and Well), and the concept took off from there.”

The scenerio at the old Hit Factory on West 47th Street was as follows: King would stand in the middle of the room and sing and play his songs, and the rhythm section surrounding him would come up with parts and eventually an arrangement. After several run-throughs, they would record a few takes.

Jemmott played his 1964 Jazz Bass (which would be stolen soon afterward), strung with La Bella flatwounds, and he went direct and through an Ampeg B-15 in the room. Feeling that his sound came from his fingers and the instrument, though, he requested that only the direct signal be recorded.

The Thrill Is Gone is a 12-bar minor blues written by fellow bluesman Roy Hawkins (with Rick Darnell) that King had been playing as a shuffle for years, but he wasn't quite happy with it. That soon changed when Lovelle put a locked-down, straight-eighth R&B feel to it.

Still, Szymczyk wondered what to do with the tune afterward. He joked, “How about B.B. with strings?” After a laugh, they realized it might just work. Arranger Bert de Coteaux was called in, and he balanced his violins with a stabbing cello part inspired by Lovelle and Jemmott's syncopated interplay.

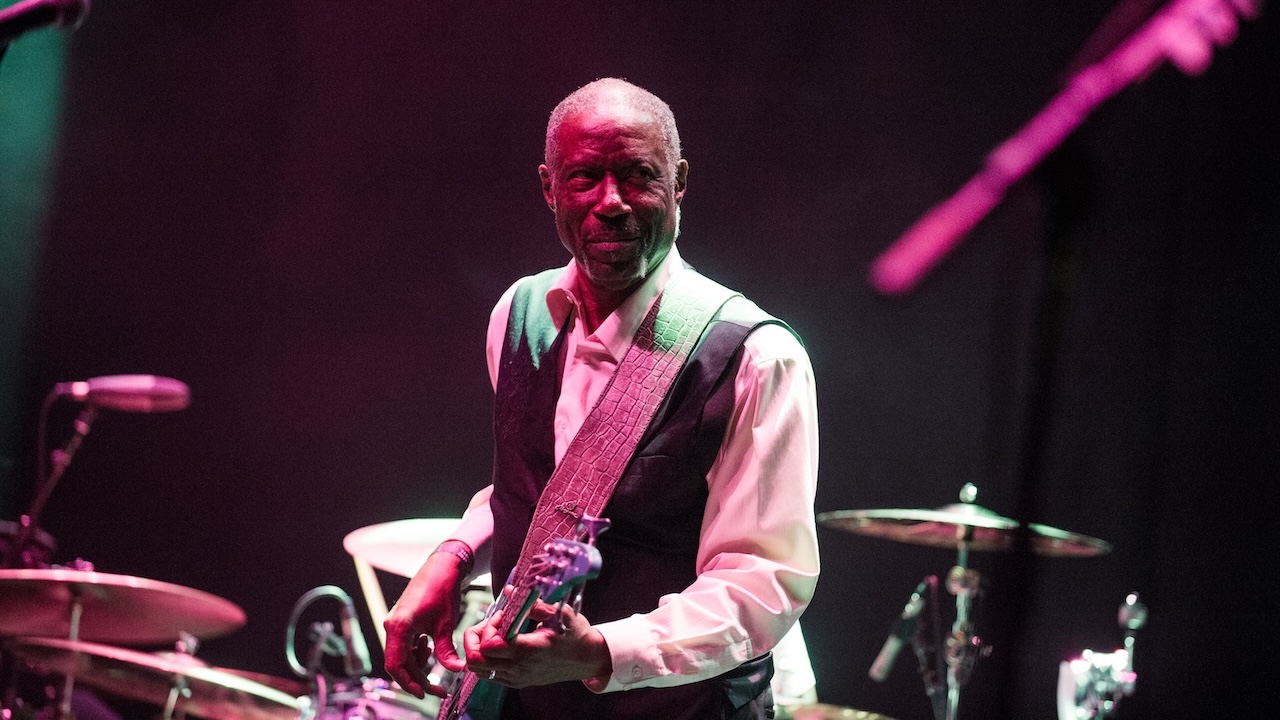

The track begins with Lovelle's drum fill and Jemmott's pickup note – the move that defines his part – leading into the 12-bar intro.

“What came to me, hearing the song, was the way I played bossa novas on upright: that subtle half-step-below approach. But on electric bass it was too pronounced, so I slid into the tonic to make it smoother.

“To me, it was a two feel, like Think, but with an added pickup and an extra eighth-note after one and three. Herb and I always thought in half-time.”

With the pattern firmly in place, Jemmott adds variation via his ascending or descending lead-ins to the next chord change. Of note is Lovelle's kick drum pattern, which often puts two 16ths against Jemmott's eighth-note pickups.

“Herb and I would lock without playing the exact same figure. It enabled us to enhance the pattern and the song, and it freed us up to do what we wanted within the support framework. It was like a conversation between us.”

Also of interest is the Gmaj7 chord in the turnaround, which is usually a dominant 7 chord in the standard minor blues form.

Jemmott continues his previous 12-bar path in the first sung verse, save the different lead-in in bar 16. The second sung verse, features the entrance of light strings and more Jemmott variations, including his use of quarter-notes.

King's first solo chorus is at 01:38, with an increase in the presence of the strings and Jemmott's slick lead-in. For King's second solo turn, at 03:14, Jemmott introduces an effective new move by dropping to a quarter-note on beat two.

He continues this into the first part of the rideout, which stays on the tonic into the fade (with probing cellos back in). “It was a way to lock it down and ride out into the sunset, and the steady tonic fit with the song's somber mood.”