*

October 28, 2019

Some towns choose to remember, and some towns to forget. Jefferson, tucked into the bottomland hardwoods and black bayous of East Texas, remembers plenty. This community of 2,000, which is often called “the most haunted town in Texas,” opens its oddly-angled streets to visitors, inviting them to tour the historic antebellum houses among the blooming dogwoods, ride the riverboats, or join one of the twice-weekly ghost walks and learn more about the dead-but-never-forgotten: men shot in streetside skirmishes, visiting railroad barons and hotel owners, soldiers and fever victims.

Yet some stories haunt through their absence, by living in a void between the spoken and unspoken, where what’s buried turns restlessly beneath the dirt. In July, I joined a crowd of around 25 people at the Kahn Hotel in Jefferson for a ghost tour. (October may be the month of the occult, but ghosts sightings can be monetized year-round.) Jodi Breckenridge, a local amateur historian who has been leading tours in the area since 2004, ushered us through the brick streets downtown as evening fell, speaking through a microphone that squealed and chattered with static. The tour route changes often, she told us, and relies largely on her own archival research; she strives for a balance between historical rigor and paranormal anecdotes. “To me it’s not an interesting ghost story unless you know why it’s a ghost story,” Breckenridge informed the crowd. “And that means there’s a historical basis for it.”

Over the following hour and a half, block by block, she transported us with stories. Gun battles at the Kahn Hotel (a former saloon built in the 1860s) that led to visitor accounts of strange electrical malfunctions and ghostly laughter; a desolate bride and a nameless menace in room 19 in the closed Jefferson Hotel; ghosts of children dead of yellow fever at the Schluter House. She showed off historical landmarks, too: the 1907 Carnegie Library (one of only four still open in the state), and the Heywood House with its mural of Jefferson’s past, “The Golden Era,” a collage of confederate uniforms and chandeliers and booming townscapes arranged around a massive riverboat.

These stories seem like testaments to Jefferson’s memory. But early in the tour, we strolled over to the opulent white front of the Excelsior House, the oldest hotel in East Texas and one-time destination of notables like railroad magnate Jay Gould. The Jessie Allen Wise Garden Club bought and restored it in the 1950s, and operates it to this day. It is their strict policy not to acknowledge any ghosts, Breckenridge said: Go up to the front desk and ask if the hotel is haunted, and they’ll deny it. Hauntings run against the tone of genteel heritage that the garden club is trying to cultivate. Breckenridge’s stories are kept outside the doors, and what visitors experience inside is their own business. It struck me as a model for the town as a whole: A place where history is so entrenched, so celebrated, and yet so much is so very silent.

*

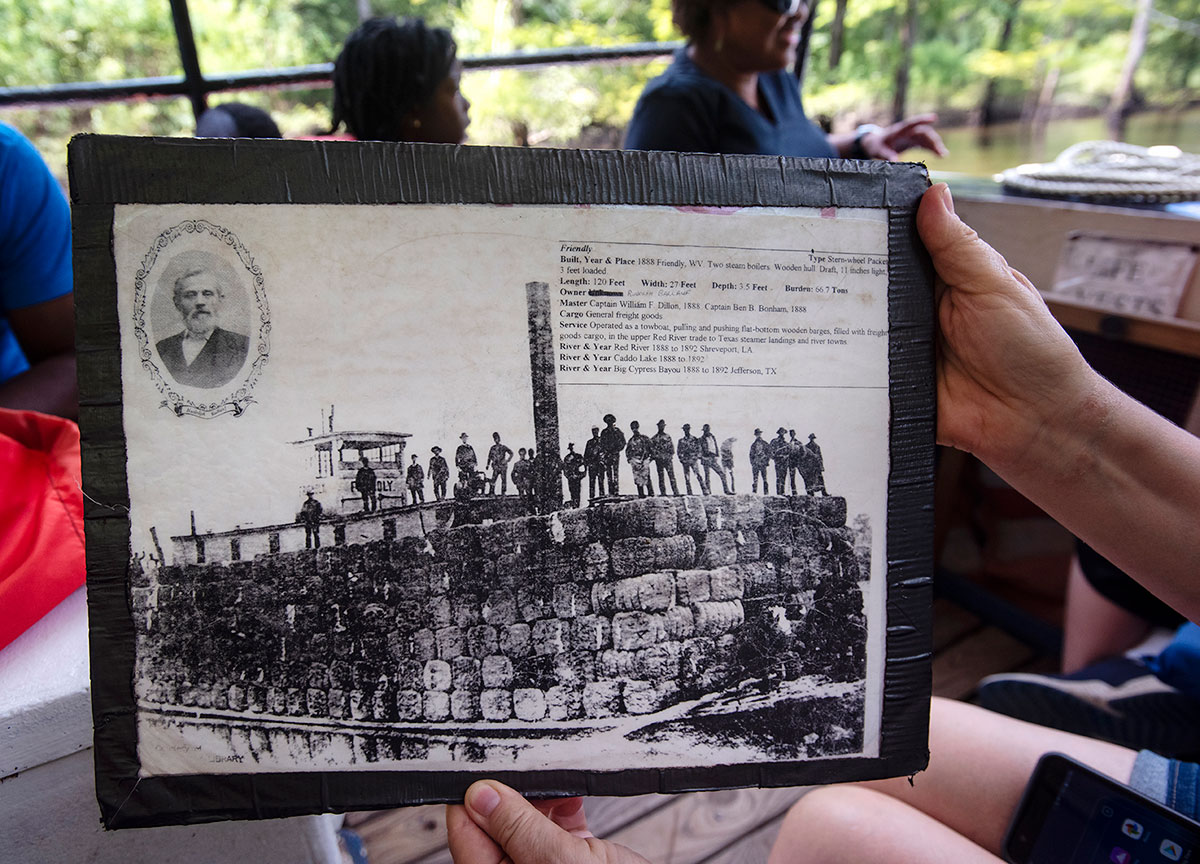

From 1845 to 1873, Jefferson was one of Texas’ most important trade centers, its sixth-largest and second-richest settlement. The source of its prosperity was the Great Raft, a millennia-old log-jam that blocked the upper reaches of the Red River. The dam deepened the bayous enough to allow steamboat traffic to pass all the way up from New Orleans, through Caddo Lake and up Big Cypress Bayou to Jefferson’s bustling port. Cotton grown on Jefferson plantations sat in towering bales on the riverside docks, and the town’s streets thronged with a polyglot mixture of plantation aristocrats, European immigrants, merchants, and rivermen. Meatpacking plants, mills, and factories sprouted up in the 1860s to supply the Confederate Army with clothing, iron ore, and gunpowder. Even under federal occupation after the war, Jefferson thrived.

It couldn’t last. In 1873, the Army Corps of Engineers used a potent mixture of dynamite and dredging to break apart the last remains of the Great Raft, dropping the water levels and making it all but impossible for steamboats to navigate up from New Orleans. The city’s population fell from roughly 10,000-12,000 to around 3,000. The major railroads passed Jefferson by in favor of Dallas. The bayou docks were filled over and all that remained of the factories were overgrown piles of rubble and casings. By 1900 the town was dying.

Heritage tourism revived Jefferson. In 1940, the garden club began hosting a “dogwood trail” that brought tourists to see the springtime blossoms. From there the group transitioned into tours of historic homes, later adding the Pilgrimage Festival, which continues every May with attractions like the 19th-century Diamond Bessie murder trial, a craft fair, and a Civil War re-enactment. (Though as amateur historian Mitchel Whitington points out, “enactment” is the proper term, since Jefferson never actually saw a battle.)

Nostalgia kept Jefferson afloat as surely as the river had. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, buses from across Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana disgorged ladies’ clubs, church groups, and schoolchildren. Antique stores and bed-and-breakfasts sprouted throughout town; almost every building along the main thoroughfare got its own historical plaque. The busses are a bit thinner on the ground these days, and the bed-and-breakfasts now compete with Airbnbs. But visitors still have their pick of restored hotels and Victorian homes, plus attractions like horse-drawn carriage rides, the Jefferson Historical Museum, Oakwood Cemetery, and even Scarlett O’Hardy’s Gone With the Wind Museum (though neither the novel nor the film has a Texas connection).

And then there are the ghost tours. Roughly four of them run year-round, with Breckenridge’s stopping at up to 10 places across town. But the stops the tours don’t take say much about the town’s history.

*

George Washington Smith was a former union lieutenant and a failed businessman, a reconstructionist Republican and outspoken advocate for the rights of freed slaves. The year he died, in 1868, he was acting as a delegate to the state constitutional convention, as elected by the black citizens of Jefferson. In a town where rebel resentment and white supremacy bubbled in a toxic brew, these were dangerous things to be.

On the night of October 3, he was walking back from a Republican meeting with a friend, the freedman Anderson Wright, when a group of townspeople led by R.P. Crump, a town notable with whom Smith had argued earlier in the day, fired on him out of the dark. Smith returned fire, wounding two of Crump’s men and sealing his fate. Charged with assault by the civil authorities, Smith sought sanctuary at the federal garrison. But following assurances of his safety, the civil authorities—including Crump—were allowed to take custody of him and of four black citizens: Wright, Lewis Grant, Richard Stewart, and Cornelius Turner. On the evening of October 4, around 70 Jefferson citizens assembled under the banner of the Knights of the Rising Sun, a white supremacist group that arose with the first incarnation of the Klu Klux Klan. Smith was shot to death in his cell; Lewis Grant and Richard Stewart were murdered somewhere on the road, the jeering crowd making so much noise that—Whitington said—a man supposedly came out from one of the houses and asked them to take it somewhere else. A badly injured Anderson Wright and Cornelius Turner managed to escape.

For two months following Smith’s death, bands of armed night riders rampaged through the lands around Jefferson, burning homes and cropland and terrorizing black citizens. In Jefferson, as the military declared martial law and began arresting suspects, the leader of the Knights of the Rising Sun skipped town; Hinche Mabry, one of the defense attorneys, was implicated in the testimony and fled to Canada to avoid arrest. Of the 35 men arrested and kept in the stockade, 24 went to trial. After 71 days of grueling testimony, including appearances by Wright and Turner, just three men were found guilty of the murder, with three more going down on a lesser charge and eventually getting a presidential pardon. Soon afterward, federal forces began withdrawing from Jefferson.

Smith went down in history as a carpetbagger, his friends as nameless freedmen. In a sense, they are the lucky ones: Their story is still told at all, memorialized in a historical marker where the jail that held Smith used to stand. No markers exist explaining how, in 1866, a town deputy marshall in Jefferson murdered two black union soldiers in cold blood and kept his post. Breckenridge did not mention in her tour that army officials filed a dispatch to the 41st U.S. Congress reporting that at least seven named black men and women were murdered by white supremacists in Marion County from 1871-1875, along with “a very large number of colored men killed [in 1874-75], that we are unable to recall their names … and a very large number of colored, that we cannot call their names, in the year 1871, 1872, and 1873.” In this, the county was representative of the region as a whole: All but 15 of 322 recorded Texas lynchings occurred in East Texas. Yet the Jefferson Historical Museum, which finds room for an exhibit on historical weapons, various antiques, a cabinet of Caddo Indian artifacts, and a large model train set, doesn’t acknowledge them.

The oral history of hauntings I encountered in Jefferson rarely included stories of black men and women. Only the Grove, a historic home where Whitington leads tours, mentioned one: a well-respected barber named Charles Young, who bought the house in 1885 and whose family lived in the house for almost a century. Whitington says he’s never seen him, though a few of his guests claim they have. It is a benign sort of visitation by all accounts—a man coming back to a house he loved. Of those who died by terrorism and racial violence, or were worked to death on plantations—stories that might haunt the 30 percent of Jefferson’s population that identifies as black—there’s little trace.

*

“There’s not a conscious effort not to talk about [race],” says Mayor Charles “Bubba” Haggard, who’s lived in Jefferson for more than 60 years. He pointed to the ongoing efforts of the local Today Foundation to renovate the Union Missionary Baptist Church, which served as a focal point for Jefferson’s black community for a century after Reconstruction. “We have a history and if someone wants to ask about that stuff, there’s historical markers … We’re a tourist town just like everybody else. We cater to the stuff that people want to do, and that’s that.”

But which stuff, and which people? This kind of cognitive dissonance is common in places that wrap their identity in heritage tourism, says Hilary Green, a professor of history at the University of Alabama and co-author of an upcoming book about Confederate monuments. The things that might make a town look bad—a history of white supremacist violence, for example—are quietly elided in favor of more agreeable topics. “Even members of the African American community don’t talk about it, or talk about it in hushed tones,” Green said. “Jefferson is trying to respond to contemporary issues with a very much sanitized, never-existed past … So it’s a question of whose history matters, and whose history should matter, and whose history doesn’t.”

This conflict has lately appeared on the national stage, Green pointed out, as tours at Monticello and South Carolina’s McLeod Plantation have begun directly addressing slavery. Some white visitors have reacted angrily, reports a recent Washington Post article, with accusations that tour guides are “politicizing” the past. But while some plantations are now attempting to reckon with their history, antebellum culture in America has for decades been sold as a sort of aspirational dream: gardens and beautiful white houses. It can be painful to be confronted with the fact that for many people, that gorgeous house was a slave-labor camp. Why talk about such horrid things at all?

“Speaking personally, I say history should never be forgotten, but humanity must not dwell in the past,” Kari Alexander, executive director of the Marion County Chamber of Commerce, wrote in an email to the Observer. It’s a bit rich to argue for not dwelling on the past when so many in Jefferson literally dwell in it: old buildings on old roads, shaped by long dead hands, holding the past in a crushing embrace. For many in Jefferson, it’s a comfortable history, and they’d like it to stay that way. “In this day and age, with people trying to be politically correct about everything, you don’t want to offend anybody,” Breckenridge said of her ghost tour. “There are definitely certain things you kind of tiptoe around … Because I know a lot of places do have tensions and things, and we don’t have that here.”

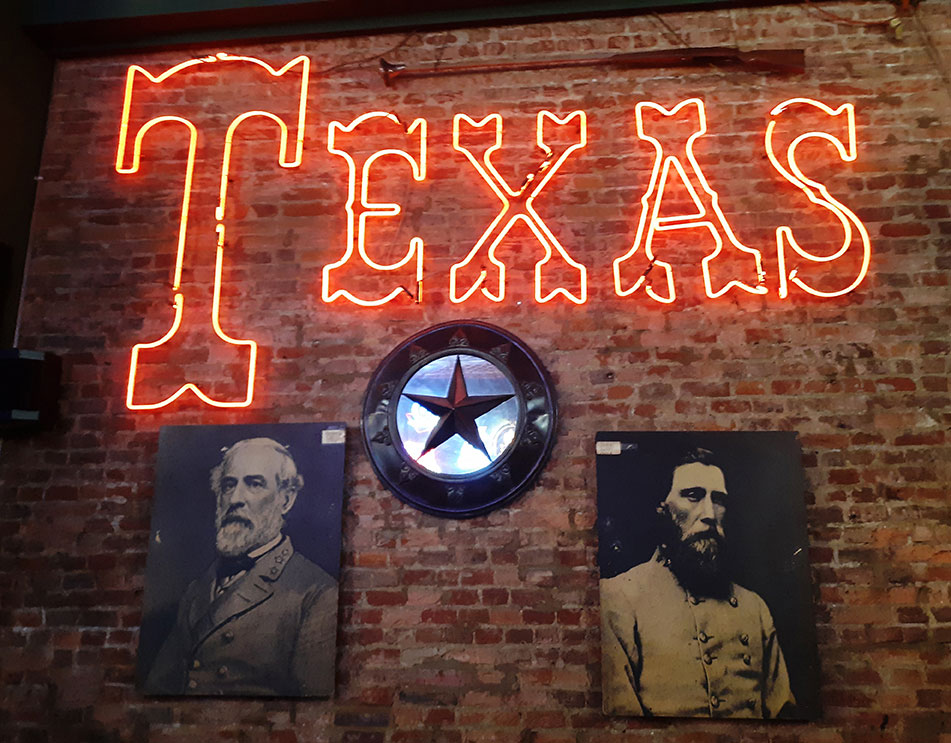

And yet there was a tension in that town, one I felt the longer I stayed. After the ghost tour I wandered over to Auntie Skinner’s Riverboat Club, a bar next to the historic saloon where the ghost tours meet. A portrait of Robert E. Lee stared down from the wall; “We support our Confederate heritage” stickers decorated the napkin dispensers. Everyone there was white. A few miles outside of town, I saw a house selling lawn statues of black men with coal-colored faces and goggling eyes out of a minstrel show. Each of them felt like a momentary glimpse of something larger beneath the surface.

Jefferson is full of that haunted logic. The television turns on by an invisible hand; the rocking chair rocks in the absence of rocker; an invisible foot sounds upon the stair. Reality is affected without an apparent cause, and that cause is inferred and uncanny, a hole in things visible purely by its negative shape. Like the question of who precisely grew the cotton that made Jefferson rich, or the names of the many, many who were murdered by its white supremacists and then denied even the dignity of a ghost story, of being allowed to reach back into the world.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Author William Lopez on How Immigration Raids Inflict Long-Lasting Trauma: “There are 364 other days in the year when people’s lives are shaped by the possibility of deportation or a raid.”

-

‘El Paso Will Never Heal’: Three Months Later, the Border Town Still Reels: El Pasoans share the deep and expansive trauma that the Walmart massacre has inflicted, and they’re urging lawmakers to take action.

-

Bonnen’s Downfall Proves Politicians Don’t Mind Dirty Laundry—So Long as It’s Never Aired: The Texas House Speaker announced his resignation, becoming another example of the trite adage: it’s the cover-up, not the crime.