It started for Basil Sylvester Sterling, better known simply as Bunny, behind closed doors at private clubs. No talking, no shouting, just cigars and ancient patronage for the boxers in the clouded ring.

Sterling fought over six rounds when he turned professional, losing his first three fights and returning to Kentish Town in north London, still an Irish and Caribbean slum in 1966, from the swanky surrounds of the high-ceilinged halls in Piccadilly where he made his money.

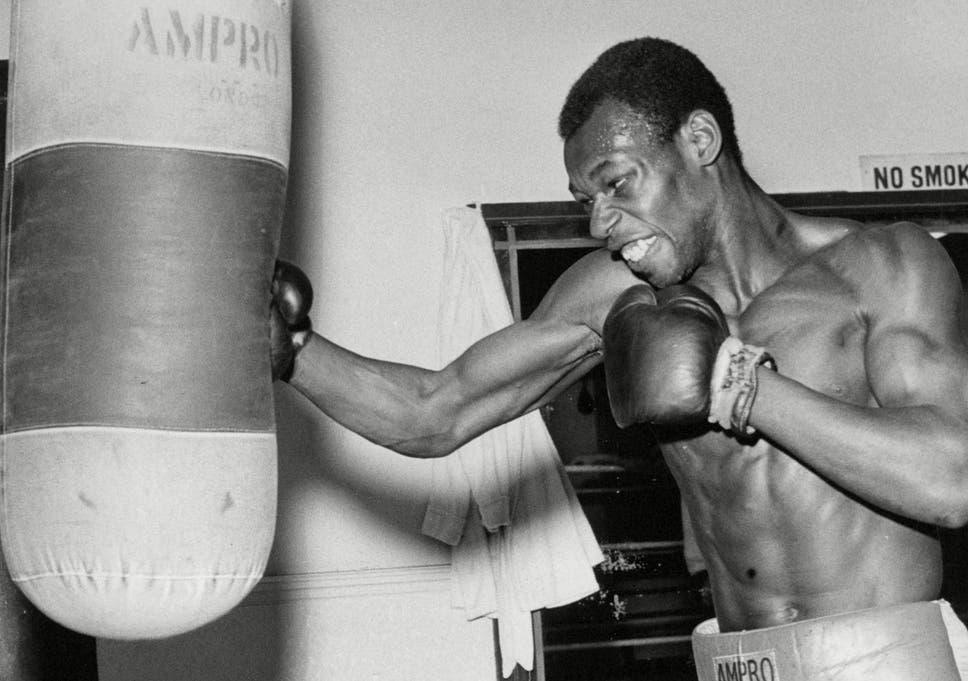

“It was tough from the very start, tough for me,” Sterling told me in 2010. “I had to take the fights and they were hard fights. It was either accept or not fight.” Bunny and George Francis, the trainer he had first met at the St Pancras amateur boxing club, were boxing outsiders in the late 60s; a black fighter and a white trainer with a gym filling up with other black fighters, Caribbean boxers, Windrush men and some Africans. Francis was fearless.

Sterling arrived in London from Jamaica when he was eight for a funeral, stayed, and died last Friday. He was 70 and he was the first immigrant boxer from the West Indies to win a British boxing title. He was also a gentleman, a skilled fighter and pioneer at a time of great ignorance and prejudice.

“I would get called a n***** lover and asked how I could have a gym full of so many monkeys – unbelievable stuff,” said Francis. “It never bothered me, it never bothered the fighters. Those were different days. I will tell you one thing, they all had to fight that bit harder for the respect.”

In 1970 Sterling fought for the British middleweight title at the Empire Pool, Wembley, against Mark Rowe, the beleaguered sport’s number one attraction at the box-office at the time. Rowe was blond, could really fight and was from the south London borders with Kent. Rowe’s fans packed the faded hall – it was a crumbling dump then – and reacted angrily when Sterling stopped their hero in four bloody rounds to make history. There were disgraceful scenes at ringside that night and Sterling was not meant to beat their idol. Sterling had won just 16 of his 27 fights when he entered the ring that night after a long wait, delays, fighting back-to-back eliminators, going on the road to make a few quid and being treated like an outsider. Sterling had become a very good fighter in adversity, in fights he had no chance of winning and in the 50-50 fights that a white British prospect would simply not have to accept. Sterling and Francis had no choice, Sterling was just one of the many black men in Britain desperate to get a living from the old sport. A black fighter could not be a prospect: well, nobody told Francis and Sterling that.

In many ways Sterling’s crazy journey started once he had the title. He was forced to go on the road, having three Commonwealth title fights in Australia in the next 18 months, a fight in Canada, one in Jamaica and a European title loss in Paris. In Britain the promoters were never desperate to use Sterling, never convinced that a black fighter could ever be an attraction, sell tickets, unless he was an American in the opposite corner, and it was two years and 11 fights before he defended his British title. There was also a rematch with Rowe in 1973 at the Royal Albert Hall and Sterling did it again, this time on points over 15 rounds. However, his wins, losses against good boxers overseas, his talent all failed miserably to move him any closer to anything like a world title fight.

Sterling was promised fights, promised riches and he joined a long list of black and white British boxers in the 70s who simply never had the opportunity they so deserved. Sterling was never bitter about his rejection, he knew that in the north London gym, run by Francis, there were others with harsher tales to tell. Francis would get his world champion in 1974 when John Conteh won the WBC light-heavyweight title and again in 1995 when he guided Frank Bruno to the heavyweight title.

Sterling lost his British title one night behind closed doors, again at the Hilton Hotel in London’s Park Lane. The bow-tied diners stashed their cigars in ashtrays to salute the 15-round fight with polite applause; Sterling lost to Kevin Finnegan and was paid just £1,500 at a time when other British boxers were getting as much as £20,000 for title fights.

A year later Sterling fought for the vacant middleweight title when he met the current British light-middleweight champion, Maurice Hope, who was born in Antigua, at the Café Royal, near Piccadilly. It is a fight that defies logic, even the warped logic of the men that put fights together back in the ancient 70s. Sterling stopped Hope in eight rounds, but four years later Hope became the first black immigrant British boxer to win a world title. Sterling won and lost the European title in his next two fights, in Germany and Italy, and quit the ring in 1977 after 57 bouts. Sterling was a young old man when he walked away, scarred, aged before his time and without the cash to live in luxury, but a bizarre meeting with a Saudi royal during his fighting days led to a career in the oil business. Hope would have to go on the road, travel to Italy and win his world title. These men were making history, forgotten history now and still getting paid tiny amounts in fights stacked against them. Sterling was the first, a decent man fighting against dreadful odds and somehow succeeding.