It’s a word that’s been gleefully co-opted by both sides of the political spectrum for their most basic rallying cries (F*** Joe Biden. F*** Trump), and it’s having a veritable heyday this week in the wake of US presidential election results – as Republicans and Democrats exclaim the expletive with polar-opposite emotion: F*** yes versus F*** no.

In Germany, one weekly newspaper even went so far as to run a Wednesday piece with a one-word headline featuring only the four-letter profanity. “F***,” Die Zeit wrote bluntly.

Luckily, as the world deems the swear word uniquely applicable in various capacities after an emotionally exhausting and far-reaching shift in US politics, there’s a brand-new edition of a book dedicated to the definition, uses and etymology of the f-word.

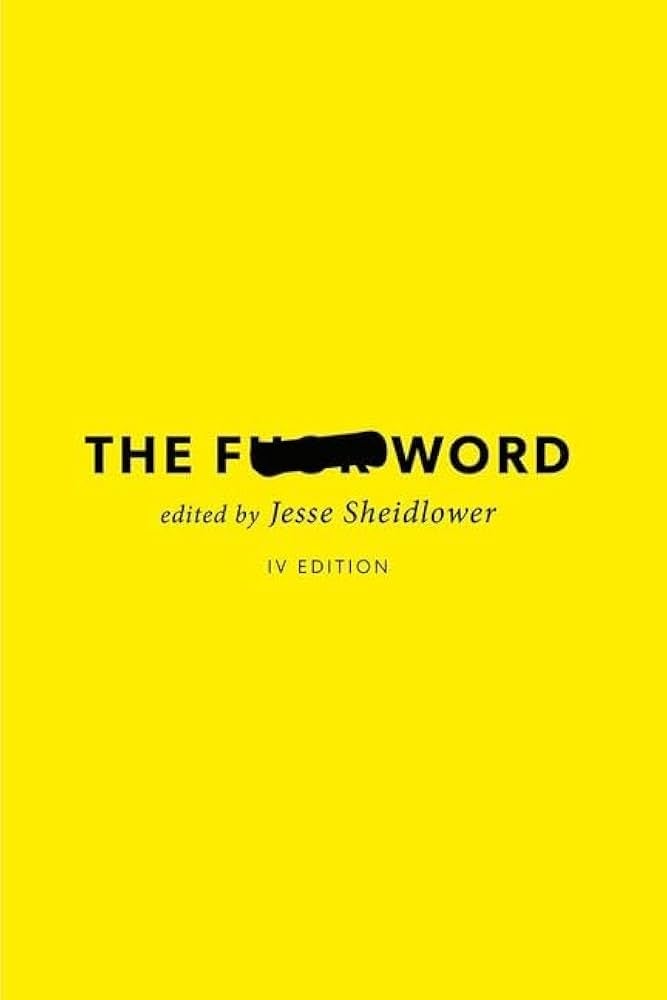

Originally published in 1995, lexicographer Jesse Sheidlower’s The F-Word has a new fourth edition out this week with major revisions addressing rapidly changing attitudes towards “f***” in public discourse, as well as pushing back by almost 200 years the known history of “English’s most notorious and colorful word.”

Sheidlower — who also just happens to be distantly related to this reporter through marriage, a fact she found hilarious at age 13 as an only child in a household where swearing did not exist — has had an interest in the word since at least first grade, when he went up and asked the teacher what it meant.

The word “f***,” he tells The Independent, “is something that everyone is interested in, but that, until fairly recently, we didn’t actually know that much about – because really, until the last couple of decades, it was not considered appropriate for scholars to work on stuff like this.

“There were academics who did study it but couldn’t really publish it, and a lot more people who wouldn’t work on it because it would be a career-killer.”

Attitudes have certainly changed in academia, media and society; as an expert studying the word’s history and evolution, Sheidlower confirms that its use in the political arena has indeed become “increasingly common.”

“There is a certain coarsening of discourse in the political spectrum lately,” he says, and “we’re willing to acknowledge that this is out there” – whereas, in the past, politicians’ vulgarity would go unreported, considered “unacceptable.”

Sheidlower doesn’t believe, however, that more muted attitudes towards the usage of “f***” have eased the word’s bite.

“It’s still something that you don’t want your young children to say or you don’t say casually – because they still do have an impact,” says the editor of the edition whose first definition explains “absof***inglutely.” The second-to-last entry is “ZFG” – an interjection defined as “zero f***s given” and “used to express extreme indifference.”

Abbreviations ranging from AF to DILF have been added in between; Sheidlower cites everything from song lyrics to scripts from The Wire in his thorough lexicographical tome.

Researching the history of the word has been fascinating, he says – and, frankly, f***ing fun.

“That’s one of the reasons I wanted to do it in the first place,” he says.

After all, who doesn’t want to know more about a word that, for many people and in many situations, simply seems to be the absolutely best summation of affairs?

“It sounds good,” Sheidlower says, musing on why the word has so captivated humans for centuries. “It feels good to say … you’ve got a hard consonant in there, it’s short, it’s punchy, it sounds like it’s the right thing to say.”

It’s certainly been employed quite frequently in many communities across the country – particularly in the buildup and letdown around the presidential election.

“There are a lot of people who’ve said, ‘Boy, do I need this word this week,” Sheidlower says.

Here are a few juicy tidbits from “The F-Word” fourth edition and the lexicographer himself.

The word has been known and used for centuries – just not necessarily recorded officially

You might use the f-word in pain, despair or anger; maybe you’re a fan of “f*****g” as a descriptor, such as when you’re “f*****g” scared. But how often would you utilize that phrasing in a work email or college essay?

“Things that are not written down are things like ‘f*****g’ as an intensifier – it’s not sexual and it’s not threatening; it tends not to get written down,” Sheidlower tells The Independent. “One of the most common or most obvious uses of ‘f***’ is as an interjection, meaning damn or whatever. To express anger or regret or hatred or something like that, you’re just saying ‘f***’ – as many people have been saying this week.

“And the problem with that, that’s not the kind of thing that gets written down much.”

The first known appearance of the word in a dictionary came in 1598, he writes in The F-Word. Other clear evidence of the word’s utilization in society has been discovered in legal documents and, unsurprisingly, historical pornography and erotica.

Earlier and earlier written mentions of f*** are being found

“Previously, the earliest clear example, the incontrovertible example, I would say, was from the late, late 15th century,” Sheidlower tells The Independent – but now, a “historian who worked on legal records found very clear examples from 1310 of a man with the name Roger Fuckebythenavele.”

No, that isn’t a typo.

“It’s funny; it’s incredible,” he says. “It seems this has to be a joke or misreading or something, but in fact … it seems to be his actual name. His name appears seven different times over the course of almost a year in these records.”

The man was accused of a serious offense which is unclear, but Sheidlower says the name seems to refer to either an activity Fuckebythenavele had tried or hint the man was “so stupid that he thought this is how you do it.”

“If this is true, well, that’s great,” he says. “It’s 150 years before the next earliest example” of the word’s usage.

“This is a recent discovery,” he says. “I mean, obviously, the records have been sitting there forever, since 1310, but someone going in and reading them … that pushes the history of the word.”

Smart-asses have been using “f***” to pull mischief for centuries

Sheidlower writes in The F-Word: “Reporting a speech delivered by Attorney General Sir William Harcourt, the Times printed on January 13, 1882 … ‘The speaker then said he felt inclined for a bit of f***ing.’

“It took the stunned editors four days to run an apology for what must have been a bit of mischief by the typesetter: ‘No pains have been spared by the management of this journal to discover the author of a gross outrage committed by the interpolation of a line in the speech …

“This malicious fabrication was surreptitiously introduced before the paper went to press. The matter is now under legal investigation, and it is hoped that the perpetrator of the outrage will be brought to punishment.’”

A telephone pioneer may have given us historical “f***” clues

“Alexander Graham Bell, of telephone fame, did a bunch of work on other kinds of audio technology … and there are recordings from 1885 that are retrievable,” Sheidlower tells The Independent.

“And in one of these recordings, someone is reciting Mary Had A Little Lamb, and it’s barely audible … and in the middle of it, there’s some kind of technical glitch, and the speaker seems to say, ‘Oh, f***.’

The utterance is “very hard to hear,” he admits, but seems likely to be the four-letter word – “so that’s really important, because … that was probably very common at the time, and it pushes it back 45 years before we knew” the word was being used in such a frustrated interjectory context.

The 45th – and newly re-elected US president – has already made “f***” history

The first appearance of the four-letter word on the front page of The New York Times came on April 19, 2019, Sheidlower writes in The F-Word.

“On being informed that Robert Mueller had been appointed as the special investigator to study Russian influence on the 2016 election, President Trump said, and the paper printed in full, ‘This is terrible. This is the end of my presidency. I’m f****d,’” he writes.

It turns out that he wasn’t, though – and it’s a safe bet that America will be hearing a lot more of the F-word from voters and officials alike as the country prepares for a second Trump White House.