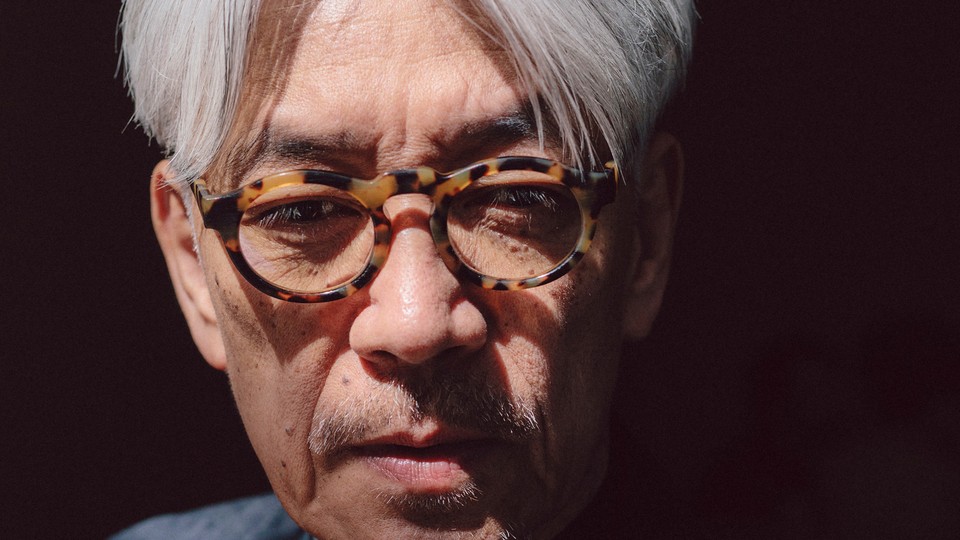

Ryuichi Sakamoto, the Japanese composer, producer, and actor who died last Tuesday, was a musician of sophisticated talent. For many, the way he intermingled cacophony with dense synth, and his interest in both silence and sound, made Sakamoto timeless and avant-garde. But for me, Sakamoto was first and foremost a conjurer of layered emotion, as exemplified in his many film compositions.

Sakamoto’s scores weren’t tinkly and whimsical like Alexandre Desplat’s, nor were they sweeping and dramatic like John Williams’s. Sakamoto wrote music that made living in an emotional in-between space audible, as in several of the orchestral songs in The Last Emperor and in the opening piano of Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. Sakamoto’s music was interested in the intersection of beauty and terror, the way a soul can survive even as a body falters.

Before I learned to love Sakamoto, my mother loved him. After her days studying textiles in a women’s college in our hometown of Nagoya, Japan, she would go home and play the Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence theme over and over on her upright piano. Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence was Sakamoto’s first film score, and the work that brought him global attention. The movie follows the complicated relationship between a captain in the Japanese army (played by Sakamoto) and his prisoner of war (David Bowie) during World War II. The theme is delicate, pensive, and thunderous all at once—a testament to the desire and disgust at the core of the film. The song explores wanting something while simultaneously being terrified of it, how the possibility of connection between people tangles with the cruelties of war.

When my mother sat at her piano bench, she was trying to mold herself into the most appealing woman and bride that she could be. Still, her childhood desire for a bigger life refused to die. It makes sense that Sakamoto’s testament to the mercurial, convoluted nature of wanting would wind so tightly around her. Years later, when she played Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence on that same piano, now transported to our Chicago home, her hands would crash down on Sakamoto’s percussive, distraught bridge. I wondered if she was thinking about how her younger self could never have imagined the reality of living away from her home and family. Both the joy of a dream fulfilled and the sorrow of its stark realities commingled in Sakamoto’s score, pervading our living room.

Sakamoto’s genius for articulating the contradictions of existence arises again and again: in the score for The Revenant, with the musician Alva Noto; in the looping meditation of “Bibo no Aozora”; in the startling quiet of his last album, 12. In my life, his music has continued to score the liminal spaces where words falter but emotions thrum. I’m still playing Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, now at the electric piano in my living room, as I puzzle through becoming a new mother, frightened and elated at once. Maybe someday my daughter will hear me play Sakamoto’s music, and it will help her understand her life too.