Concerned about potential problems during the next election when Congress counts presidential votes, some legislators are interested in reforming the federal law that governs that process, the Electoral Count Act.

Reforming the act, which sets the procedures for how votes for president are counted in the Electoral College, means identifying what it’s supposed to do, the areas that need reform and any other problems with it.

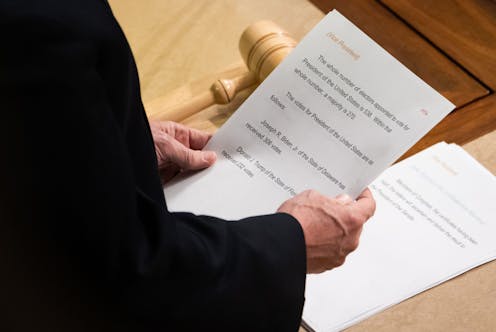

As a scholar of election law, I recognize that presidential elections in the United States are complicated. Voters do not directly elect the president. After Election Day, and based on the popular vote, each state chooses presidential electors who formally meet and cast votes for president that are then relayed to Congress. There are 538 electoral votes, and after Congress counts them and verifies that one candidate has received a majority – at least 270 – the winner of the presidential election is declared.

In theory, a rule about how to count votes seems easy enough. But it’s hardly been easy.

Abusing the act

During Reconstruction, the period after the Civil War, Congress faced contentious questions over whether Southern states appropriately appointed presidential electors. At other times, two sets of competing electors for different candidates were sent to Congress.

The Electoral Count Act was enacted in 1887 to streamline rules after the disputed presidential election of 1876.

But in recent years, the act has revealed some weaknesses.

The act allows members of Congress to object to counting votes from a state. They can do that if one member of the House and one Senator write an objection. The Electoral Count Act does not list what kind of objections are proper, leaving it to Congress to decide if objections are appropriate or not. If this kind of dispute arises, Congress can debate what to do with the electoral votes.

The objection mechanism was used just once in the first 100 years of the act.

But in 2005, members of Congress objected to counting Ohio’s electoral votes cast for George W. Bush, alleging the results were inaccurate because of voter suppression and faulty voting machines. Congress spent two hours debating whether to count the votes. Other members of Congress unsuccessfully attempted to object in 2001 and 2017 to other states’ electoral votes – no senator joined those objections. In 2021, members of Congress again objected to counting Arizona’s and Pennsylvania’s electoral votes for Joe Biden, alleging a variety of claims, including fraud, which forced Congress to spend more time in debate.

These objections have undermined confidence in the outcome of presidential elections. Members of Congress publicly aired baseless claims that the election results were in doubt. There was no serious reason for Congress to doubt the outcome of the 2020 election.

One reform might simply increase the threshold required to file an objection, from one member of each chamber to, say, one-fifth or one-third of the members. That would speed up counting and reduce opportunities for members of Congress to take grievances to the floor.

Power that does not exist

Another problem that has emerged relates to the vice president’s role in counting electoral votes.

An impetus for the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol was a mistaken belief that Vice President Mike Pence could ignore the Electoral Count Act and unilaterally refuse to count electoral votes from some states or indefinitely delay counting.

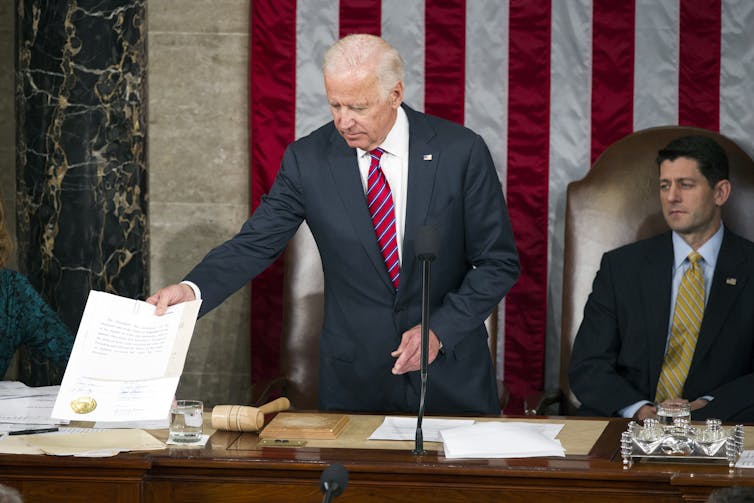

The Constitution mandates that the President of the Senate – typically the Vice President – open the certificates of electoral votes from each state. In addition, under the current Electoral Count Act, the President of the Senate presides over the meeting, calls for objections, and generally moves the process along.

Pence did so, despite intense pressure from President Donald Trump to reject the Electoral College votes that would formally make Democratic candidate Joe Biden president.

But there are worries among some members of Congress that another vice president might be tempted to assert power that does not exist. A vice president might create chaos by claiming that some votes should not count, or telling Congress what it can or cannot do, setting off a fierce debate in the middle of the count.

So another reform to the act might make it clear that the vice president has no role over the meeting except ministerial acts like opening the envelopes from presidential electors. That clarity reduces opportunities for mischief in the future.

These two concerns reflect the narrow role of Congress in counting votes and the mechanics of that meeting.

Improvement - or more complexity?

There are more ambitious changes to federal law that Congress might examine, but these also raise thorny problems.

For instance, some Republican state legislators in 2020 – encouraged by Trump – suggested they could appoint their own electors well after Election Day if they were dissatisfied with the results certified by the state’s election officials.

Some cited a provision in federal law that if the state “failed to make a choice” for choosing presidential electors on Election Day, the state legislature could appoint them later. But this provision was designed for states that required majority winners in presidential elections and might hold a runoff after Election Day if no candidate received a majority.

Congress could repeal this “failed to make a choice” provision and insist that Election Day is Election Day, with no opportunity under the statute to second-guess the results. But there are complications that arise with even a simple reform like this.

A state might suffer a terrorist attack on Election Day or be hit by a hurricane the night before. Should the state have a chance to hold its election a week or two later? And if so, how does Congress define the circumstances when a state could hold a later election?

Other proposals call for more robust involvement of the federal courts. From my perspective, it seems better that the judiciary should review serious challenges to the vote before Congress counts. Federal courts have been increasingly active in reviewing election-related cases ever since the Supreme Court’s contentious decision in Bush v. Gore affecting Florida’s recount in 2000, which resulted in Bush winning the election.

But that can invite additional questions. Elections are run by states, and states already have extensive procedures in the canvass, recount and audit of their votes.

When and how should federal courts get involved? It’s not clear that courts could do anything differently – or, more importantly, better – than they already do. And it may invite every presidential election – close or not – to end up in federal court, inviting a dozen Bush v. Gores each election.

One benefit of Electoral Count Act reform is that it lends itself toward bipartisanship. No one knows what future presidential elections will bring. Republicans and Democrats in Congress have both expressed disapproval of some states’ presidential election outcomes over the last 25 years, and it’s not clear who will be disappointed next.

Congress cannot prevent all mischief, but it can reduce the possibility of mischief in the future. Congress can address some of the easier questions, like the threshold for objections and the role of the vice president. It can also have serious conversations about some of the more controversial questions. It can determine if an amended law can make things better – or just invite more complexity and controversy.

Derek T. Muller does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.