One of my life’s aims is to swim in as many lakes, rivers, pools and oceans as I possibly can, to use my liberty and swimming skills as freely as I can. I love the feeling of being in a large, fresh body of water, its soft immersive, vast or deep buoyancy.

I’ve swum in a freshwater lagoon near Acapulco in Mexico, with the guide reassuring us there were no crocodiles in the water that day. I’ve swum in a busy London indoor pool noisy with swimmers thrashing about and in Australia’s only women’s pool. I’ve swum in the Weisser See lake on the outskirts of Berlin, the same lake that my grandmother swam in, before fleeing Germany. At Jaffa’s Alma/al-Manshiyah Beach, in Tel Aviv, I’ve looked up from the sea to the Mahmoudiya Mosque’s minaret.

I’ve marvelled at finding myself in waters so far from home. It turns out that my ability to swim makes me part of an elite.

Review: Shifting Currents: A world history of swimming – Karen Eva Carr (University of Chicago Press)

Karen Eva Carr opens Shifting Currents with the startling information that today worldwide – for all Earth’s many rivers, creeks, lakes, ponds, seas and oceans, to say nothing of built pools, canals and theme parks – the majority of people can’t swim. People might bathe and wash their clothes in rivers and lakes, or undertake ritual ablutions in bathhouses, but the vast majority must keep their feet on the ground.

Yet the earliest humans from over 100,000 years ago taught themselves how to swim, for food and for pleasure. There is a long history of human swimming for utility and leisure, amply recorded in pictures from the earliest cave drawings and folk narratives.

This year the OECD reported that only one in four people in low-income countries can swim. Low to middle-income countries report more non-swimmers than swimmers, and a majority of those not able to swim are girls and women.

Access to natural waterways has decreased world-wide through the privatisation of foreshores and beaches, and the building of dams, roads, ports, the development of wetlands, and larger cities.

It takes time to learn to swim, is especially difficult as an adult to learn, and do-or-die – it’s impossible to fake.

It hasn’t always been the case that worldwide most people could not swim, though as Carr’s world history shows, swimming abilities have shifted over time, along with weather patterns and across geographies. People have migrated, conquered, traded, competed and shared stories that celebrated entering the water or warned of its dangers and need for sacred respect.

Leer más: Friday essay: morning thalassa – the calm, salt therapy of Sydney's women's pool

Neanderthals swam

The earliest humans swam. Neanderthals living in Italy about 100,000 years ago swam confidently. Their ear bones show they suffered from swimmer’s ear from diving 3–4 metres to retrieve clamshells they then shaped into tools.

During the last major Ice Age of 23,000 years ago, when glaciers reached south to England, northern Germany, Poland and northern Russia, swimming, if it had been present, was abandoned. Over the next tens of thousands of years, people didn’t swim.

Across the continent of Eurasia, people turned to farming wheat and millet for bread, and began to eat less fish, a food that is rich in vitamin D. In order to absorb more sunlight, and produce sufficient vitamin D necessary to good health, these populations developed genetically lighter skin. Some of these lighter skinned white people then migrated south and their descendants, the Greeks, Romans, Scythians and Iranians continued to be non-swimmers right through to the end of the Bronze Age, even in places that had remained warm during the Ice Age.

Thousands more years passed, and then rock paintings at Tassili n’ Ajjer in southern Algeria show depictions of people moving in a horizontal posture with their arms outstretched. Quite possibly they are swimming.

By 8000 BCE, in the Cave of Swimmers in western Egypt, small red figures swim.

Another 5000 years pass, and Egyptian hieroglyphic texts and imagery are replete with representations of swimming. Egyptian kings swam, as did poor Egyptians. Many Egyptian girls and women swam, and quite possibly Cleopatra swam. Mark Antony could swim.

Swimming was common throughout the continent of Africa, and stories about swimming for fun and pleasure along with hunting and foraging, are found in many traditional tales. In the Ethiopian story of “Two Jealous wives”, the twin babies thrown into the river are quickly rescued by swimmers. A humorous West African tale tells of a stingy woman who eagerly jumps into the river to swim after a stray bean.

Overarm is the oldest swimming stroke depicted. In Egyptian, Hittite, and early Greek and Roman images people are shown swimming, alternating their arms and sometimes using a flutter kick with straight legs, the same stroke we’re routinely taught in Australia. Greek and Roman swimmers are not shown putting their faces in the water, and breaststroke is absent from ancient imagery and stories.

Only in Plato’s Phaedrus is there a mention of backstroke, suggesting that a man “swimming on his back against the current” is behaving foolishly. Sidestroke is used when swimmers need to push canoes or carry something aloft through the water.

Assyrians created possibly the earliest flotation devices, habitually using a mussuk made from goat skin to help them stay afloat in the fast-moving rivers of eastern Syria and norther Iraq.

In ancient Eurasia swimming was linked to multiple and opposing myths about racial superiority. When associated with a darker skin colour, populations who swam were especially dehumanised. By the first century BCE for instance, North Chinese writers were racialising swimming, associating Southern Chinese peoples’ familiarity with ocean swimming and eating of fish to their darker skin colour.

North China was part of the northern Eurasian non-swimming “zone”, and for these northern-hemisphere non-swimmers, water was sacred, dangerous, sometimes magical, and not to be polluted by human bodies.

The Greek historian Herodotus remarked that Persians took great care to,

never urinate or spit into a river, nor even wash their hands in one; nor let other people do it; instead, they greatly revere rivers.

Cultural difference expressed through swimming is present throughout the historical narratives as one people observes another and mark themselves as different, depending on how well, or not, the other culture swims. It is also often a marker of class. Wealthier Greek and Roman women sometimes took up swimming. Augustus’ great-granddaughter, Agripper the Younger, was a strong swimmer. When she was stabbed during an assassination attempt on her son, she escaped by swimming across a lake, her attackers unable to follow.

Not all cultures swam in the ancient world. Across Europe and northern Asia, in Mesopotamia (Syria, Iraq and Kuwait) and Southwest Asia, people did not swim, were afraid of the water, and the real and imagined creatures of the seas and lakes. Carr’s history explores the reasons for this non-swimming through a wealth of archaeological, text-based and pictorial sources.

Leer más: Guide to the classics: The Histories, by Herodotus

Sexuality and slavery

Carr shows that it’s not only warm weather that decides whether a community will swim or not, but other cultural and political factors. She describes her history as also a study of whiteness and white culture. The part that swimming plays in world history is not neutral.

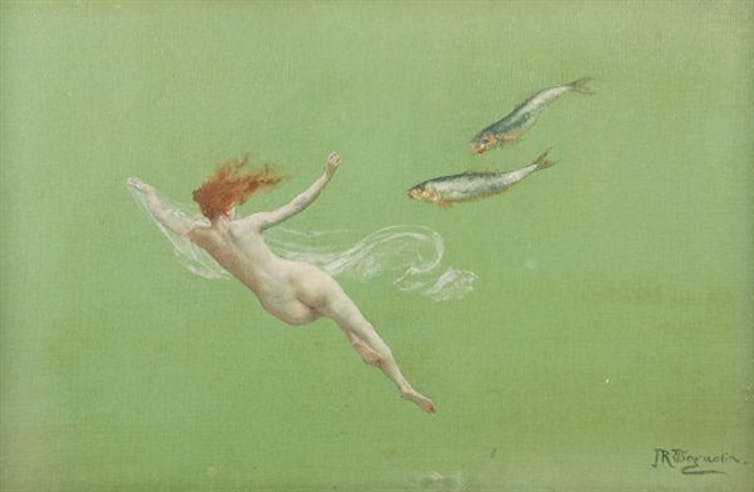

Swimming was often associated with sexuality and promiscuity. Ovid, for instance, frequently evokes swimming as an erotic prelude to rape in the Metamorphoses. A medieval tale from Central Asia tells of Alexander the Great and a companion hiding behind a rock to spy on women swimming naked. In many tales and images, the sight of women and girls swimming semi-clothed or naked is linked to shame and titillation.

Leer más: Guide to the classics: Ovid's Metamorphoses and reading rape

Swimming is closely bound up in the history of patriarchy. Trial by water for suspected witches and the ducking of women and girls as punishment, was practised in Europe for centuries – even up until the 1700s when wealthier Europeans and European-Americans were learning how to swim.

Slavery’s connection to swimming cultures emerges with Muslim slave traders, who associated Central African nakedness with promiscuity and likened the ability to swim to animal behaviour. Across the continents of Africa and the Americas, later medieval and later European explorers also invoked people’s swimming skills as a justification for their enslavement.

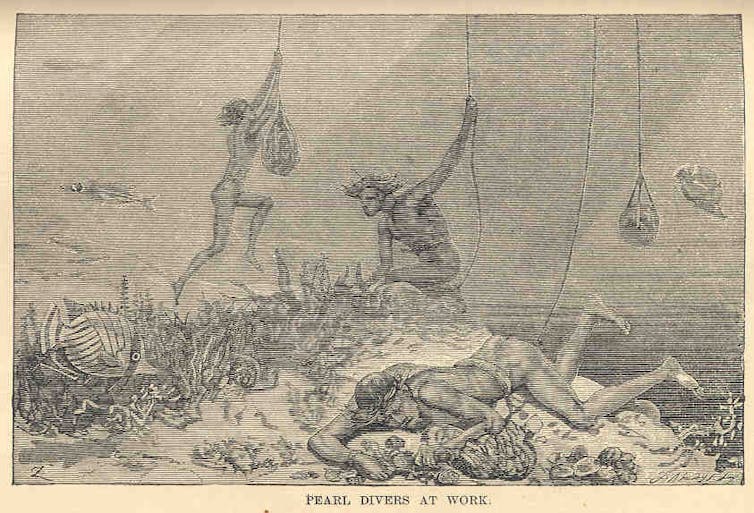

Nevertheless, slave-holders expected the African and Native American slaves to swim in the course of their work. Slaves dived to clean ships, served as lifeguards for white swimmers, swam when tracking escaped slaves, and salvaged lost goods from shipwrecks. Enslaved Native Americans worked as pearl divers in the Americas.

Amidst this economic and educational history of inequity worldwide, swimming could be described as the pastime of the elite, and certainly Carr believes it has become so.

Carr’s fascinating history is very well structured, with chapters clearly titled for readers who might want to dip into certain epochs or themes. It is weakest in the modern-day analyses, drawing too-ready conclusions about contemporary situations. (For instance, Carr’s analysis of the reasons for the 2005 Cronulla Riots doesn’t mention the Howard government’s anti-migration stance or Islamophobia post-9/11.)

Australian First Nations and Pacifika histories are also only sketched in. Nevertheless, this ambitious work achieves its aims of being a fascinating and highly informative world history, written for the lay reader with an interest in this rich topic, and beautifully illustrated with mono and colour images, an index and chronology.

Leer más: Hidden women of history: Wauba Debar, an Indigenous swimmer from Tasmania who saved her captors

Jane Messer no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.