I’d like to drive less, exercise more, commune with nature, and hate myself with a lesser intensity because I am driving less, exercising more, and communing with nature. One way to accomplish all of these goals, I decided earlier this year, was to procure an e-bike. (That’s a bicycle with a motor, if you didn’t know.) I could use it for commuting, for errands, for putting my human body to work, and for reducing my environmental impact. A cyclist I have never been, but perhaps an e-biker I could become.

I wouldn’t be alone. The pandemic drove a 240 percent surge in e-bike sales from 2020 to 2021. The reasons are hard to pin down but easy to surmise. Typical bikes sold out everywhere. Solo riding outdoors seemed less risky than sitting with other people in an Uber, a bus, or a train. Gas prices got worse as quarantine lifted. E-bikes became the world’s best-selling electric vehicles in 2021: This could be the moment “micromobility” advocates have long anticipated, when more eco-friendly vehicles begin to change urban transit forever.

But I’ve been trying to live with one, and brother, I’ve got some bad news. These things are freaks. Portraying e-bikes as a simple, obvious, and inevitable evolution of transportation (or even of bicycling) doesn’t fully explain these strange contraptions. The same was said of Segways, and then of Bird scooters, and both flamed out spectacularly.

[Read: Unfortunately, the electric scooters are fantastic]

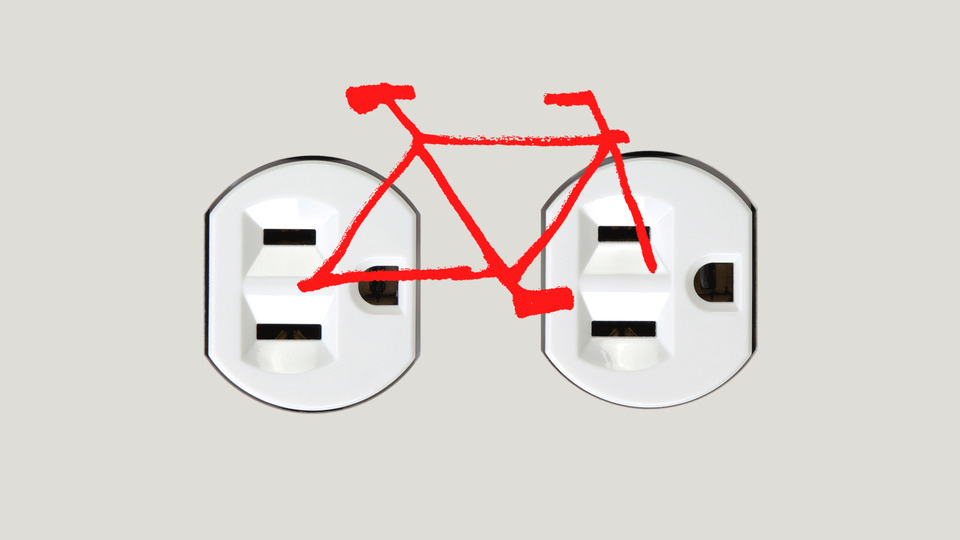

Bikes have always worn many helmets: cycling as exercise, cycling as leisure, cycling as sport, cycling as transit. These roles often conflict with one another. The commuter sneers at the spinner, who pedals pointlessly to nowhere. The leisure-rider spurs the Lycra-racer, who endangers pedestrians and inspires drivers to hate cyclists. E-bikes continue, and worsen, that disorder by jumbling up aspects of bicycles and motorcycles. Strapping a motor to a bike turns out to alter more than just speed and exertion. It produces a chameleon that takes on, under various conditions, both the best and worst features of a variety of transportation technologies. The result is less an evolution of a two-wheeled machine than a pastiche of the many things such a device represents. It’s a monster made from bicycles and motorbikes.

Here’s what I mean: A bike can be exerting to ride, which is both a feature and a defect. Biking to the store or office offers an opportunity to move one’s body instead of spreading it into the seat of a car (or even a train). Depending on distance and terrain, biking can raise your heart rate, making it an effective workout. But working out can make you sweaty and smelly, a feature incompatible with using a bike for commuting (or even errands).

E-bikes, by contrast, allow a motor to assist the rider, reducing exertion and thereby delivering you to the office or cheesemonger with a dry brow and dry armpits. But in exchange for that polish, an e-bike rider gets less exercise than the equivalent trip under full pedal. There’s some debate about this matter, and of course it all rests on the assumption that the rider hasn’t purchased a fully motorized model that demands no exertion whatsoever. Some studies suggest that you’ll get a lot less exercise from pedaling an e-bike than normal biking, while others say certain e-bike riders could enjoy greater health benefits if motorized cycling encourages them to ride more regularly.

The truth will differ based on circumstance, but the result is the same: a weird ambiguity. An e-bike sure seems like a way to cheat at exercise, even if it really facilitates it. That’s been my experience; the credit my Apple Watch gives me for “outdoor cycling” on my e-bike pales in comparison to the exertion I undertake at home on the Peloton. (Apple has added an e-bike-detection algorithm in this mode, which both underscores the fact that e-biking ain’t biking, and suggests that yes, in fact, it is.)

The same murk pervades e-bikes as an alternative form of transit. In theory, the easier ride that an e-bike provides should make it more tempting than a standard bike. For people with certain mobility issues, it may indeed be. Yet for the most part, all the nuisances of biking still crop up: hot or cold or wet weather, needing to transport something heavy or awkward, taking on another errand during the day that requires a drive, and so forth. Counterintuitively, because the e-bike is easier to ride than a normal bike, I feel less inclined to adopt it as a regular practice, let alone a whole commuting identity. All the downsides of biking still remain, without the satisfaction of persisting in the face of adversity.

Perhaps my e-bike ambivalence comes in part from the bike’s strange social status. An e-bike isn’t cheap—the least expensive ones are about $1,000, and they go up to $5,000 or more. But the symbolic value one receives in exchange is minimal. Spending five large on a conventional bike would get you a status symbol—you’d come off as a cyclist for sure. For that matter, spending that dough on a Vespa would infuse you with an Aperol-tinged Italianate cool. You’d want to be seen arriving on your moped. But I don’t want anybody seeing me on my e-bike. It’s just kind of embarrassing.

Vehicles have symbolic value, like it or not. Cars denote freedom; commuter bikes imply, for better or worse, jerkitude or tweeness; motorcycles are cool; e-scooters are for douchebros. But e-bikes bear no clear character. They fall between the cracks. Even when I willingly tell people, “Oh, I got an e-bike,” I’m not sure if I’m bragging or revealing shame. “Mmm, wow,” they respond, before changing the subject to something more interesting, such as the weather.

Coolness is related to danger and risk, and safety plays a part in e-bikes’ weirdness, too. A motorcycle is unabashedly cool, but it’s also quite dangerous in return. A moped is arguably even riskier to drive, especially a model that can’t go very fast. Sharing the road with much larger cars traveling much faster can make small-motorbike transit a more harrowing affair than biking on trails or separated bike lanes. But here, too, things get murky. At full power, some e-bikes can go as fast as 49cc mopeds (20–30 miles an hour), tempting riders into joining actual traffic. But then, at that speed, an e-bike on a trail or a sidewalk poses a greater risk to its rider, to fellow cyclists, and to pedestrians. E-bike accidents seem to be more severe than those encountered on traditional bikes, mostly because e-bikes go faster, thus increasing the consequence of impact. And as e-bikes become more popular, such calamities may become only more common.

In my experience, e-bikes are also strange to ride, and that strangeness contributes to their oddity. Having a motor changes a lot of things about a bike. Anytime you pedal with the motor engaged, it will push you forward more than you’ve pedaled. I thought I’d acclimate to it, but I still haven’t; especially when pedaling from a coast out of a turn, I forget the motor is in gear, and when it engages it sends me off course, flying into the curb (or worse, into traffic). The e-bike rolls into an uncanny valley, the chasm between a bicycle under my human power and a motorbike piloted directly by a throttle.

Even the sonic pleasures of motorized or nonmotorized two-wheelers are up for grabs. A motorcycle signals power (and maybe a caricature of outmoded masculinity) from its exhaust. But a bicycle makes no noise apart from the whir of its crankshaft and the chu-chunk of its derailleurs. My e-bike is pretty quiet, but the motor does whine at me when it engages. The battery, attached to the frame like a water bottle, also rattled like a jalopy before I strapped it fast to the down tube. At every moment, the e-bike reminds you that it’s not quite a bicycle, nor yet a motorbike.

The micromobility advocates present new (or newly popular) personal-transit vehicles as a Cambrian explosion for transit that might snuff out the supposedly evil automobile. In this view, the more options out there, each tuned for a different purpose, the more likely that small, clean, human-scale transportation will win out over chunky, dirty machinery. So far, they have not been right. Bird, the e-scooter giant, was valued at $2.3 billion at the start of 2020, and now it’s a penny stock with a market cap that hovers around $120 million. Moped sharing never caught on. None of these new conveyances has yet gained desirable cultural associations, either.

Currently, e-bikes are trapped in the weird smear between pathetic, loser bicycles and pitiable, low-end motorbikes. Especially in America, where bike infrastructure is far less developed than in the small, flat nations of Northern Europe that cycling advocates like to exalt as a model, e-bikes have become kind of a nuisance. Walking the streets of New York City, it now feels just as likely that you might get mowed down by an e-bike as a taxicab. Elsewhere, the narrow protected lanes and greenway trails built for human-powered bikes—already littered with stroller-pushers and joggers—don’t quite scale to the new swiftness of e-bikes. The pathways and roads themselves, perhaps already unsafe at bike speed due to uneven pavement and poor maintenance, feel even more dangerous on a not-quite-motorcycle.

E-bikes’ identity crisis might seem like the symptom of a transition: As soon as adoption really takes off, all of these issues could work themselves out. But I’m not so sure. Something is ontologically off with e-bikes, which time and adoption alone can’t resolve. Whether as bicycles haunted by motorbikes or as mopeds reined in by bikes, e-bikes represent not the fusion of two modes of transit, but a conflict between them.