Three years ago, the State of Mississippi arrested a 67-year-old grandmother with no known criminal record at her office.

Nancy New was a lifelong educator. She had run her nonprofit, Mississippi Community Education Center, for more than 25 years. When state auditor Shad White’s agents interrogated New on multiple occasions, she didn’t even bring an attorney, according to a person with direct knowledge of the meetings. At the end of one of those interviews, one of New’s alleged accomplices, 63-year-old accountant Anne McGrew, expressed surprise that the auditor’s agents had guns, the person says. The agents explained that while they worked for the auditor’s office, they were not auditors. They were state police.

Shelley Mays/USA TODAY NETWORKS

At that time, they were focused on the state’s welfare-agency director, John Davis, and two former professional wrestling brothers he allegedly enriched. But the misspending of welfare funds went far beyond that. Investigators kept peeling back layers of the scheme until they arrested New and a handful of others, at which point White declared, “The scheme is massive. It ends today.”

Only a few weeks later—after investigators stumbled upon more information, more was leaked publicly and the story exploded—did a more full picture come into focus:

New was mostly following orders from Davis, the welfare chief.

Davis largely operated on behalf of Mississippi’s then governor, Republican Phil Bryant.

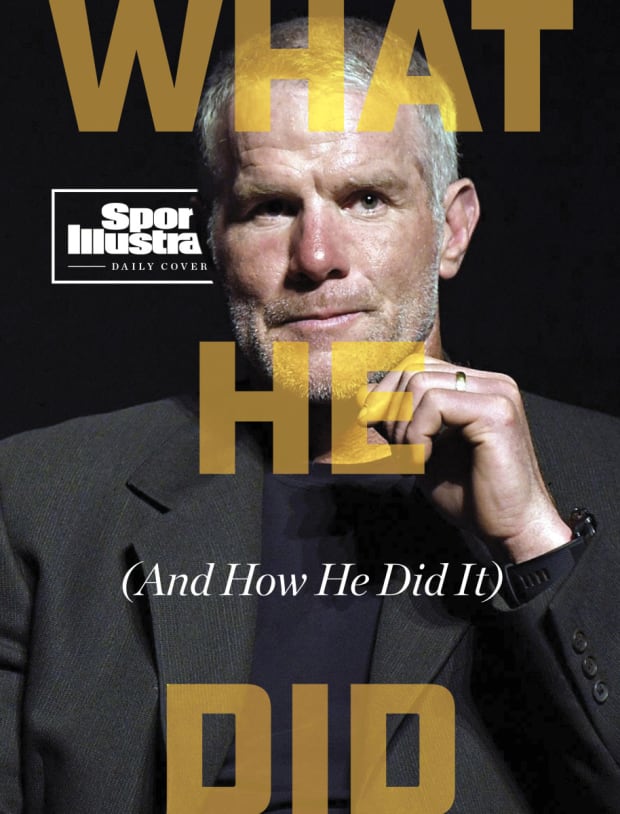

And Bryant worked relentlessly to please the state’s most famous athlete, NFL legend Brett Favre.

Favre has portrayed himself as an unknowing and tangential participant in the welfare-embezzlement scheme. But it appears nobody benefited more. Interviews and an analysis of legal filings and records, which include dozens of text conversations—some of which have not previously been public—paint Favre as a ringleader from start to finish.

Favre had promised his alma mater, Southern Miss, that he would build a volleyball facility for his daughter Breleigh’s team there. But he was obsessed with not paying for it himself. So he got Mississippi’s welfare agency to build indoor and beach volleyball facilities for him—using money intended for the poorest people in the nation’s poorest state—and then he kept pushing to get more for a business venture, with the governor often helping him, according to texts from those involved.

“Brett Favre’s repeated demands for this grant money were certainly the driving force” for millions of dollars in illegal transactions, says former U.S. Attorney Brad Pigott, who had been hired by current Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves to independently investigate the scandal—until Pigott started looking at the volleyball deal and Reeves fired him.

Favre was a leading character in a drama full of political alliances and personal favors; of celebrities and their sycophants; of unchecked power and unconscionable use of federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds. Illegal behavior was so institutionalized that some perpetrators showed no fear of getting caught. One of Favre’s business partners referred to Bryant as part of his “team,” to which the governor replied, in part: “We will get this done," according to texts Sports Illustrated obtained over the course of several months of reporting. The governor texted Favre about “our cause.”

When it unraveled—starting with an accidental, seemingly innocuous discovery—the most powerful players started outmaneuvering the others. Eventually, people who plotted with one another plotted against one another—a theme that continues to play out in both ongoing civil and criminal cases.

Mississippi Today’s Anna Wolfe won a Pulitzer Prize for her exemplary reporting on all aspects of the scandal. SI set out to explain and examine Favre’s role.

At times, the former quarterback comes off as comically clueless. Often, he seems highly manipulative. Throughout, he was relentless in his pursuit of government money. After Davis was forced out of his job at the Department of Human Services and the scheme started to splinter, Favre kept pushing. At one point he told New, “I’ll keep asking weekly.” Shortly before the arrests, as he fretted about securing cash, he wrote in a text, “I [can’t] focus on anything else with this looming.”

Three years later, something else looms over Favre: the distinct possibility he will be indicted.

This is the story of what Favre did—and how he did it.

Allen Steele/Getty Images

On April 20, 2017, Favre sent his first text message to another prominent Southern Miss alum:

“Hey governor this brett Favre.”

He got to the point quickly: “Deanna [his wife] and I are building a volleyball facility on campus and I need your influence somehow to get donations and or sponsorships. Obviously Southern has no money so I’m hustling to get it raised.”

Bryant, who was returning from a trip to Cuba, wrote back:

“Of course I am all in on the Volleyball facility. Y’all have fun and next week come see me. We will have that thing built before you know it. One thing I know how to do is raise money.”

Bryant finished with the thumbs-up emoji. He said he was going on a turkey-hunting trip soon but would meet Favre for lunch when he returned.

From there, the scheme developed with startling efficiency.

First, Jon Gilbert, Southern Miss’s athletic director, told Favre to contact another USM alum: Nancy New.

New was a USM Athletic Foundation board member who had founded two private K–12 academies for nontraditional students and those with learning disabilities. She had also founded charities for dyslexic or autistic children and was executive director of the nonprofit Mississippi Community Education Center.

In 2012, when Bryant became governor, he recruited New to be his nominee for the state’s superintendent of education position, according to a person familiar with the discussions. She indicated she would accept, according to the person, then changed her mind, preferring to continue running her private schools and MCEC. But as Bryant streamlined Mississippi’s Department of Human Services, the state subcontracted most welfare distribution to outside organizations. New and another organizer, Christi Webb, got the biggest portions—combined, about 40% of the total—and split the state geographically between them, distributing the welfare money to a range of programs. In three years, MCEC went from $3.06 million in revenue to $26.87 million—and from employing a total of 38 people to employing 135.

MCEC had long applied for and received public funds. But New, who had a social relationship with Bryant and his wife, Deborah, had no government background. Now she was responsible for doling out millions in welfare money in Mississippi, one of the country’s most economically and racially divided states—while she continued to run MCEC and own her private schools.

The arrangement also left New and Webb beholden to Davis. They set their budgets ahead of the fiscal year, but Davis controlled when they got money and how much they received.

So in September 2017 when Davis pushed New and Webb to hire his friend, former wrestler Brett DiBiase, they did not flinch.

Davis: “The plan is for each of you to hire Brett at $125,00x2 or was one of you doing that. He will need insurance as well. Also, travel money for him to shadow me.”

Webb: “Nancy and I want to split.”

New: “let’s get this worked out tomorrow first thing.”

New’s organization ended up paying DiBiase the entirety of his $250,000 annual salary, considerably more than New’s salary ($156,500 at the time)—even though Davis had already hired DiBiase himself, at MDHS, as his “director of transformational change.”

When Davis wanted New and Webb to redirect TANF funds toward Brett DiBiase’s brother Teddy Jr., prosecutors say they did that, too.

And when Davis wanted New to funnel money to Favre, the TANF cookie jar was easy to open.

Mississippi’s TANF rules can be maddeningly vague, which is why they are ripe for corruption. But welfare money was obviously not intended to build a college volleyball facility—and if anybody knew that, it was Phil Bryant. As state auditor in 2005, Bryant demanded the Claiborne County Human Resource Board repay $220,832 in TANF funds, saying, “The blatant and wanton misuse of taxpayer’s monies, especially those designed to assist families in need, cannot be tolerated.”

In July 2017, Favre texted Bryant that he was “Not sure how” they would get the facility built, but: “you are the governor and on our side and that’s a good thing. Actually a great thing.”

By then Bryant, who took office in 2012, was a hero to the political class that believes in cutting welfare. As a candidate, he said, “Churches should do a lot of the work that governments now do,” and in his first five years, Mississippi roughly halved the number of TANF recipients in the state and its amount distributed. Then, in 2017, Bryant signed the state’s HOPE Act, which forced welfare and Medicaid recipients to prove to a private contractor that they deserved to keep receiving aid—and gave them just 10 days to prove it. For this, the right-wing Foundation for Government Accountability named Bryant its Governor of the Year.

On July 24, 2017, according to court filings, Favre; Gilbert; New; and New’s son Zach met with John Davis; Davis’s deputy, Garrig Shields; and Teddy DiBiase at Southern Miss. The meeting lasted one hour—including a tour. But before it ended, Davis promised $4 million, according to the filings. The money would come from TANF funds.

It was as though Davis knew he would deliver the money before the meeting.

Bryant’s lawyers would later say he had “no knowledge of or involvement in” the meeting or the $4 million commitment. But Mississippi Low-Income Child Care Initiative founder Carol Burnett, who worked in MDHS in the early 2000s, tells SI, “The head of DHS doesn’t make those decisions without the governor’s knowledge and approval. That is just unfathomable to me.”

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

Favre was thrilled. Later that day, he texted New: “Nancy thank you again!!! John mentioned 4 million and not sure if I heard him right. Very big deal and I can’t thank you enough.” But on July 26, Favre told New he had spoken to Gilbert, the AD, and “between you and I he is very Leary of accepting a large grant.” Favre was in the unusual position of trying to convince a major-college athletic director to accept a large donation.

Paperwork for the volleyball facility was drawn up that summer. But two statutes stood in the way.

The first: The state’s Institutions of Higher Learning board can approve university projects only “when funding has been secured from whatever source.” Southern Miss needed the entire projected cost on hand.

To help, Favre offered to do promotional work for New, and “whatever compensation could go to USM.” After the scandal broke, Favre would claim that “my agent is often approached by different products and brands for me to appear in one way or another. This request was no different.” But this was Favre’s idea: “I want to help you and was thinking a PSA is one option,” he texted New, and he wondered how it would look.

Favre asked New: “If you were to pay me is there anyway the media can find out where it came from and how much?” New wrote back: “No, we never have had that information publicized.”

In theory, New had the power in this relationship. But she was extraordinarily deferential to Favre: “Please do not worry about your time commitment,” she wrote at one point. “We can only imagine how many directions you are pulled.”

One day after assuring Favre the deal would not be publicized, New texted him:

“Wow, just got off the phone with Phil Bryant! He is on board with us! We will get this done!”

Favre wrote back: “Awesome I needed to hear that for sure.”

Favre signed a deal to record one radio spot and deliver one keynote address and three other speeches for $1.1 million, according to an auditor’s report; he recorded the radio spot, but there is no indication he delivered any of the speeches.

New’s attorney has argued in a court filing that “MCEC paid Favre $1,100,000 expressly to provide Favre with additional funds for construction of the Volleyball Facility."

Favre’s attorney Eric Herschmann has claimed in interviews that Favre kept the $1.1 million in welfare funds for himself—then agreed to send USM up to $1.4 million in an unrelated transaction a few months later.

The second statute in their way involved TANF. Mississippi has few red-line restrictions on TANF funds, but there is one clear one: Funds may not be used for “bricks and mortar”—like building an athletic facility.

To get the funding approved by lawyers, a lease was drawn up. It would become public through court filings, and it circumvented the law in three easy steps:

1. Southern Miss leased the volleyball facility to its athletic foundation for one dollar.

2. The athletic foundation, a private booster club, would build a “Wellness Center” on site.

3. New’s nonprofit, MCEC, would then sublet the facility from the foundation—not for the $4 million Davis promised, but for $5 million.

Why the extra million to Southern Miss? Favre wrote to New: “I hope it’s enough now. Jon said 500k has to go to renovations for reed green and another 500 to maintenances fund.”

Reed Green Coliseum was the building the volleyball team was leaving. It is also home to USM’s basketball teams.

As New’s lawyer, Gary Bufkin, has argued in a filing, “The bureaucratic logjam had apparently been removed.” In October, Mississippi’s Institutions of Higher Learning approved the volleyball deal.

MCEC would get “certain limited use” of the facilities and not much else, according to USM records. But this way, TANF money was technically not used for bricks and mortar. The prepayment also satisfied the requirement that “funding has been secured.”

On Dec. 27, Favre received the first check for his promotional activity, for $500,000.

He texted New:

“Nancy Santa came today and dropped some money off.”

New wrote back: “Yes, he did. He felt you had been pretty good this year!”

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

New had shown Favre she could direct welfare money to him—but also that she couldn’t do it by herself.

Every year New budgeted how she would spend the money the government gave her. According to the findings of a Mississippi state auditor’s report, her record-keeping was lousy. Millions went to recipients other than needy families, like fitness boot camps and a Christian ministry and consulting firms. She directed at least $700,000 to her private schools, MDHS said. Prosecutors say after Davis started directing her to funnel money inappropriately, she did so for her own benefit: Starting in September 2017, for instance, she used state money to buy three vehicles for her family’s use. They say she paid her son Jess’s consulting firm $500,000 over two years.

This was clearly not good government. Pigott says: “None of these people seemed to give a hoot about the actual purpose of the TANF money. Much of the sloppiness can be traced to that. They just didn’t take it seriously. It wasn’t important to them.” But by all indications, New was spending the money. To help Favre, she needed to redirect money she had budgeted for something else—or she had to get the Bryant administration to give her more. That is why she kept asking Bryant and Davis for approval.

So in March 2018, when Favre texted New, “The [construction] bids are all in and shockingly the lowest is 6.9,” New had a problem. Between the lease and Santa payment to Favre, she had already spent $5.5 million. She didn’t just have $1.4 million in a desk drawer.

She wrote back: “Wow, that is disturbing. Lordy, all this time and now to find this out.” She tried to think of other creative ways to help Favre: a fundraiser at the governor’s mansion or “Phil’s business list that he offered earlier.” She said “hopefully there will be something in the new budget for Families First to offer. But that’s not til July.”

July would bring a new fiscal year and a fresh pile of government cash. But Favre didn’t want to wait. He went over New’s head—as high as he could go.

In early May, Favre texted Bryant:

“Governor this Brett. I’m still trying to save money on Vball facility.”

Favre asked Bryant about the “prison industry possibly as a builder” of lockers. Bryant, who was turkey-hunting in Nebraska, put Favre in touch with a cabinet maker and said, “I will pay for the work.” The governor, who regularly asked Favre to publicly support him or his allies, offered to do a fundraiser in Hattiesburg, Miss.

Those were legal favors. But Favre would soon push Bryant for a large, legally dubious one—and he didn’t have to push very hard.

It had nothing to do with Southern Miss or volleyball. Favre had invested $250,000 in Prevacus, a company that was ostensibly trying to develop a quick-acting concussion drug, making him its largest outside investor. Favre, who has a history of concussions, had also tried to convince other athletes and celebrities to invest; the company’s “Sports Advisory Board” was dotted with former NFL players and coaches, along with Favre’s agent, Bus Cook. In late 2018, Prevacus was looking for more funding.

On Dec. 6, 2018, Prevacus CEO Jake VanLandingham texted Bryant: “We want you to know that we want you on the team and can offer stock.” Six days later, according to records obtained by SI, he emailed Bryant’s director of scheduling and intergovernmental affairs with the subject line “Prevacus dinner with the Governor.” Eight days after that, VanLandingham texted Bryant about invitees. Bryant responded: “Have Joe Cannazaro [sic] from N.O. Owner of Traditions Medical City and his head of Nuro-Surgery so far.”

New Orleans businessperson Joseph Canizaro, a longtime donor to Mississippi Republicans, had built Tradition, a planned community on Mississippi’s Gulf Coast, and he was building a campus for pharmaceutical companies there. After Bryant left office, two of Canizaro’s limited-liability companies, The Village at Tradition and Columbus Communities, would list him as a vice president.

The dinner occurred toward the end of the month, after which Favre texted Bryant:

“It’s 3rd and long and we need you to make it happen!!”

Bryant wrote back: “I will open a hole.”

The next day, Favre directed VanLandingham to talk to Nancy New.

Shortly after that, John Davis sent out a calendar invite for a meeting at Favre’s house. Davis said the meeting “was requested by Brett Farve [sic] and the Governor to discuss the Educational Research Program that addresses brain injury caused by concussions. They also want to discuss the new facility at USM.”

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

Davis had been running point on an illegal welfare-fund embezzlement scheme in a strange way: ostentatiously. He seemed to flaunt his connection to the DiBiases. He had flown around the country with Teddy Jr.—first class, on the government’s dime, according to the auditor’s report. Over the course of three years, Davis allegedly convinced Christi Webb and New to send $3.15 million in TANF and “emergency food-assistance” funds to Teddy and his shell companies, most of it through Webb. He gave Teddy a title, “director of sustainable change”; a corner office on MDHS’s executive floor, near his own; and an administrative assistant. But Teddy was never actually employed by MDHS.

Davis also used welfare funds to repeatedly prop up Brett DiBiase, who got paid for two jobs (for MDHS and MCEC) when his behavior suggested he could barely hold one. Brett spent an alleged work trip partying in New Orleans, a source familiar with the trip says, and he got paid $48,000 to conduct opioid addiction training when he was still struggling with addiction himself, the auditor’s report says. When Brett went to Rise, a luxury rehab facility in Malibu, Calif., Davis told New to pick up the $160,000 bill, and she did, the report says. New described it in her records as “curriculum” at “Rise-Malibu Training.” MCEC tried to get Brett’s health insurance company to pay them back, one source says.

People who worked with Davis were uneasy about his relationship with the DiBiases, and Davis was well aware of it, court records and interviews show.

Nonetheless, Davis invited Teddy to the Jan. 2, 2019, meeting at Favre’s house.

When Favre welcomed Davis, VanLandingham, Teddy Jr., Nancy New and Zach New into his home, the governor was not there, but his presence was felt. Before the meeting began, Bryant sent a text to VanLandingham and Favre, referencing an apparent Bryant acquaintance. “He sounds like someone who can help our cause,” Bryant wrote. “Let me reach out to him. May need a conference call later.”

During the meeting, Nancy New and MCEC agreed to send $1.7 million in TANF money to Prevacus.

That night, Favre told Bryant: “Jake would like to follow up with Joe [Canizaro] if possible”. Bryant’s reply: “Sure..”

MCEC would ultimately send around $2.2 million in welfare money to Prevacus and another VanLandingham company, PresolMD, according to various filings. VanLandingham would refer to it as “grant money.”

When Davis and New were arrested, state auditor Shad White would accuse them of “creating a fraud scheme to take TANF funds to pay for personal investments in medical device companies.” But a copy of MCEC’s contract with Prevacus shows that New’s organization got only one thing out of the deal: “right of first refusal” for “future manufacturing and clinical sites in the State of Mississippi.” Those sites, of course, were already being planned for Tradition.

VanLandingham and Favre had their cash infusion; Bryant’s ally, Canizaro, had the inside track on a real estate deal; and Bryant had VanLandingham dangling company stock for him.

VanLandingham was a determined pitchman. He sought and secured media coverage long before he was close to FDA approval. But a few weeks after closing the MCEC deal, he met with a Canizaro friend, Peter Fos, at Tradition. Fos, who had a background in health policy, told SI that Canizaro asked him to look into whether he should put money in Prevacus. Fos says: “My recommendation to Mr. Canizaro was not to invest in it.”

Ryan Lopiccolo, the executive vice president of Canizaro’s Columbus Properties, told SI they never invested in Prevacus or PresolMD—and as for the manufacturing sites, “there were ideas floated to us about having the drug produced or researched at Tradition, but nothing ever came of it."

The News would put $350,000 of their own money into Prevacus and PresolMD, one person familiar with the payment says, ostensibly as an investment. New was excited about working with VanLandingham in Tradition. She had founded multiple autism charities and she told VanLandingham, “We would like to do a school for Autism down in that area when we make our big hit!”

VanLandingham responded: “I’ll get it going for u!!!”

VanLandingham would keep stoking New’s autism-school dream: “I’ll work on tradition deal and autism for you,” he wrote once, and “Joe Canzario [sic] is excited to hear your ideas about autism.” He even set up a meeting with Canizaro. But no autism school was ever built.

As for the News’ $350,000 investment: They appeared to get nothing for it.

A year later, VanLandingham would text his business director, Megan Munyon, and ask:

“Any chance that Nancy or Zach New signed a stock certificate?”

Munyon replied: “I don’t think I ever sent them one.”

Then Munyon followed up: “I just looked at my SC list and I never issued them one.”

On the morning of Governor Bryant’s 2019 State of the State address, VanLandingham began a text to him, Favre and Canizaro with “Hey Team.”

VanLandingham also wrote: “Governor I’m working with Nancy New on our Phase 1A funding.”

Bryant wrote back: “Great report. We will get this done.”

That night, Bryant touted Nancy New’s work in his speech, calling it “a model of success for thousands of Mississippians and one that is being emulated all across America.”

Favre was certainly a big fan. In May he sent New an update “on what is owed as of today” to Southern Miss: $1.07 million. Favre told New the plans “look great. Of course you can help out again. And regardless I owe you big time.” New said, “That number is not too bad,” and said again that she would try to find money after July 1.

On May 30, 2019, Favre—whose cost estimates tended to fluctuate—texted New: “Nancy are you still confident you can cover the 1.8 and that number will probably be less as we get closer.”

New responded: “In a meeting with John Davis now. He said we will cover much of it but may have to be in a couple of payments. We are on board!”

The volleyball scheme was almost complete. But there was about to be a break in the Bryant-to-Davis-to-New-to-Favre chain.

During a routine internal MDHS audit, an auditor noticed that one of Brett DiBiase’s MDHS paychecks went to a post office box belonging to John Davis, people familiar with the case said. That was not normal, and Davis’s relationship with the DiBiases had already raised suspicions.

The internal auditor reported it. Then DHS deputy director Jacob Black turned Davis in to the man who was best positioned to end the corruption:

Governor Phil Bryant.

Bryant had no choice. Ignoring this would be an obvious crime—with witnesses.

Bryant alerted the state auditor, Shad White—who was Bryant’s former campaign manager and a Bryant appointee. But the governor appears not to have told White about the volleyball facility or Prevacus—which, of course, would have implicated himself.

White’s agents started investigating. Davis’s nephew, Austin Smith, would tell investigators that Davis told his family Brett DiBiase used the P.O. Box because DiBiase was going through a divorce and wanted to hide money from his wife. Whatever the reasons for the P.O. Box, agents quickly discovered how easily and flagrantly Davis had funneled money to the DiBiases through New and Christi Webb.

New was worried. On July 2, she texted Bryant: “Governor, may I please meet with you for a few minutes this morning? It truly is important.”

Bryant, the leader of a state of nearly 3 million people, wrote back: “I can see you at 8:30 at the Sillers Office.”

New kept her role as subgrant contractor. But Bryant told Davis he was going to “f---ing jail,” Davis told family members, according to an MDHS filing, and then fired him.

Publicly, MDHS announced July 8 that Davis was “retiring” and “has been an inspiration to many and will be greatly missed.” The department even published a farewell letter from Davis, in which he wrote: “I have served under many leaders and Governor Phil Bryant has been the greatest.”

Ezra Shaw/Getty Images

With Davis out, the scheme was down to three principals:

Phil Bryant, the veteran pol.

Brett Favre, the relentless competitor.

Nancy New, the naive pleaser.

Favre tried to keep the team together. On July 16, 2019, he texted New:

“Nancy if I can help you in any way you know I will. Please know that.”

New wrote back: “Thanks Brett. That means a lot to me. I am ok, just politics and people. We are trying to stay above all the foolishness and we will. Too much good stuff to get done. I am concerned though that I may not be able to assist you in Aug. as we had planned.”

That same day, en route to a meeting with the governor, Favre texted Bryant:

“I’m on my way and I’m sure I wont have time [or] privacy enough to speak about this,” Favre wrote, “so I want you to know how much I love Nancy New and John Davis. What they have done for me and Southern Miss is amazing.”

Favre then went right back to lobbying the governor for money. This time, Favre told Bryant they were “planning to do workshops and youth clinics” in the volleyball facility, though there is no indication those workshops and clinics ever happened. Favre also told Bryant he paid for “3/4” of the project himself, and “the rest was a joint project with her and John which was saving me 1.8 million.” How Favre came up with those numbers is a mystery.

Favre wrote to Bryant: “I was informed today that [New] may not be able to fund her part. I and we need your help very badly governor and sorry to even bring this up.”

Bryant should have seen it was time to end this. But the governor just wouldn’t quit Brett Favre.

Bryant texted him: “I will handle that … long story but had to make a change. But I will call Nancy and see what it will take.”

Favre apparently met with Bryant for less than an hour. When the quarterback departed, Bryant texted New: “Just left Brett Favre. Can we help him with his project. We should meet soon to see how I can make sure we keep your projects on course.” New told Favre she was meeting with Bryant two days later.

Favre wrote back: “I love John so much. And you too.”

Bryant tapped his old friend Chris Freeze, a retired FBI agent, to replace Davis. Almost immediately, Bryant sent a staff attorney a text that made him seem only vaguely aware of the volleyball project:

“Can we check with Nancy New and what the contract with Southern Miss is all about. Brett is asking for info on the proposed funding.”

Brett was asking for more than that. On July 22, 2019—just two weeks after Davis announced his “retirement”—Favre texted Bryant:

“Governor this Friday Deion Sanders and his son are coming for a recruiting visit. He is a QB and could be best in country. I already with Nancy started talking about a indoor facility but I think we have got to get one to stay up with everyone else. But it won’t happen anytime soon if you and Nancy can’t help. I would like to tell him we are about to start building in the next year and half.”

The request was brazen and revealing. Bryant was a Southern Miss alum, capable of legally raising money for the football program, but the reference to “you and Nancy” was a pretty clear request for government money. Favre even applied time pressure on the governor.

Bryant knew a legal land mine when he saw one. His response read like it could have been written by—or for—a lawyer:

“The State Auditor is reviewing all the Contracts at DHS which Funds Families First. Hope we get legal clearance soon. Don’t want to get anyone in trouble for improper expenditures. Should know soon.”

Favre kept pushing: “As far as families first and facilities goes I think we can do so much together. It would be beneficial for both.”

Bryant, formally again: “Hope we get clearance.”

Favre, pushing again: “What’s your gut tell you will happen? I have to come up with a lot of money if this doesn’t get clearance.”

Bryant, formally again: “It’s the State Auditor that will give the approval. Has to have legal authority. I will check today.”

Favre, pushing again: “if I need to do anything to help make this all work please let me know.”

Bryant: “Will do.. we are checking today. Thanks for caring.”

On July 28, Favre sent Bryant another lengthy text about the Sanders family and Southern Miss. Once again, Bryant skipped any promises or turkey-hunting banter and responded with a text only a lawyer could love:

“Nancy has some limited control over Federal Funds in the form of Grants for Children and adults in the Low Income Community. Use of these funds are tightly controlled. Any improper use could result in violation of Federal Law. Auditors are currently reviewing the use of these funds by Families First. As soon as the Audit is completed we will know if the project at USM is a proper expenditure. Neither I nor Nancy can make this decision. She must have approval from DHS and the State Auditor. As soon as we get approval we can move forward. Without that approval any expenditure could be illegal and Nancy and USM could be made to repay the Federal Government any and all funds spent. That’s why we are waiting till it is approved.”

Favre got the text but missed the message. On Aug. 24, he told Bryant the volleyball facility was almost finished “and I’m sure the university will be calling for the remaining 1,048,000. I can try to buy some time. Your our starting QB and we can only go as far as you take us.”

The governor texted the quarterback:

“I got called into this game late. [...] Not sure who made the deal for a million dollars.”

It’s not clear exactly which million-dollar deal Bryant was referring to: the $1.048 million Favre said he owed, the mysterious million that was added to the volleyball lease right before Southern Miss’s lawyers approved it, or something else. But Bryant went out of his way to say he had nothing to do with it. After all, he got called into this game late.

Favre and New finally took note of Bryant’s sudden change from openly enthusiastic to detached and cautious. Favre started to play middleman between New and Bryant: calling one and relaying the message to the other, and sometimes sharing text messages from one with the other.

Favre and New needed to woo Bryant. Their idea:

The Dewey Phillip Bryant Center for Excellence at the University of Southern Mississippi.

“The proposed name was intended to be a surprise honor to the Governor,” New wrote in a letter to Bryant’s office, which became public through court filings. “Due to the urgency in getting this secured, we felt it appropriate to share.”

New called it a “collaborative partnership” among her organization (the Mississippi Community Education Center), the state government (MDHS), the USM Athletic Foundation and Favre. It was intended to provide support and resources for “healthy living and nutrition, with primary focus on childhood obesity and family nutrition” in Mississippi. New told Bryant that they needed $1.5 million to $2 million to “adequately fund” the project.

New made this sound like a new project. But two people familiar with the plan say this was just an attempt to get Bryant to send more money for volleyball facilities by naming the already approved “Wellness Center” after him.

Using government money to fund a project named after a sitting governor had worked in Mississippi the year before. After Bryant helped secure $76 million in (legal) government funding for a new medical school, Ole Miss unveiled The Phil Bryant Medical Education Building.

Favre told Bryant that “we feel that your name is the perfect choice for this facility and we are not taking No for an answer!” But New told Favre that when she discussed the Center for Excellence with Chris Freeze, “He asked if that was the one that the Gov’s name was to go on the bid.” She seemed oblivious to the optics.

“I said yes,” New wrote, “but honestly I couldn’t read why he asked that about his name. Keep that quiet right now. Lots of politics I think.”

Favre told her, “Phil is adamant it will get done. Of course he is a politician so I’m a little uneasy.”

Favre copied a text from New and sent it to Bryant, explaining how funds would be used. Favre had started presenting his requests as foregone conclusions, subtly making it harder to reject them. “Now that the facility is almost done I expect to start payment,” Favre told Bryant. “I know your on it and thanks.”

Bryant, who said he was in Ghana, was still cautious with his texts. But on the phone with Favre, Bryant was more candid—and Favre then texted New what Bryant had said, inadvertently creating a record of it.

So Bryant told Favre via text that he hadn’t seen the proposal: “Nancy has to provide the proper documentation to MDHS.”

Then Bryant talked to Favre on the phone.

And then Favre texted New: “He said to me just a second ago that he has seen it but hint hint that you need to reword it to get it accepted.

Two days later, Favre texted Bryant a Microsoft Word attachment that apparently included New’s updated proposal. The governor’s name was no longer on it. Bryant wrote back: “Looks much better. We will help from this end.” Favre and New were not sure. Favre had complained to Bryant that some people had stopped returning New’s calls.

New asked Favre: “Confidential; do you get the impression the governor will help us?”

Favre wrote back: “I really feel like he is trying to figure out a way to get it done without actually saying it.”

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

For around a month since hiring Chris Freeze, Bryant had walked a thin line: distancing himself from the volleyball project while nudging it forward. On Aug. 21, 2019, Bryant texted Freeze:

“Brett Farve [sic] is blowing me up over that proposal Nancy New submitted for the Center at Southern Miss. I have told him it would be reviewed just like all other proposed projects. Brett needs more to do in his life just now. I really do think he believes in the project.”

Chris Freeze was no John Davis. In his texts, Freeze seems fond of the governor but willing to question him. He wrote back:

“Yes, Nancy is blowing me up, too. Unless there is additional information you would like MDHS to consider, I’m not inclined to approve at this time. I don’t think now is the time to give them $2 million. We have reviewed and think there might be other ways to accomplish their goals than by creating a center at USM. Brett could be a part of those if he wanted. If you would like to talk so I can further explain, I would be happy to call at your convenience sir.”

An hour and a half later, Bryant responded to Freeze.

He used this text to check all the boxes he needed to fill—for whoever might be reading.

Bryant portrayed himself as forthright and proper: “As always I am not going to interfere.”

… as being too busy to monitor MDHS funding: “You got a better understanding than I do of these projects.”

… and as out of the loop for years: “I think Brett was told it was going to get done by the previous Director. One of the reasons that he is a former Director.”

Bryant apparently wanted Freeze—or whoever might be reading his texts—to believe he had fired Davis, at least in part, for promising to fund the volleyball facilities. But Bryant had repeatedly made the same assurance to Favre for years—and he kept doing it.

On Sept. 4, 2019, Freeze met with Bryant, New and Favre in Bryant’s office.

Afterward, Bryant texted Favre: “We are going to get there. This was a great meeting. But we have to follow the law. I am to old for Federal Prison.”

He told Favre they would have to wait “till November,” after the election to succeed Bryant, who was term-limited.

But two days later, Bryant sent a text to a staff attorney:

“She wants to meet again,” Bryant said of New. “Don’t think that’s a good idea. Keep this response as a record.”

The reply: “Yes sir. She’s relentless.”

Bryant: “Nancy is worrying. She know what they were doing was wrong.”

The reply: “100%. She should be worried.”

Bryant replied with a thumbs-up.

The trap had been set. If the volleyball scheme were to blow up—which it would, a few months later—Bryant had made it look like New was the perpetrator, Favre the accomplice and Bryant the honest occasional adviser.

But first Bryant kept telling Favre he would try to get him his money.

In October, Favre asked Bryant whether he had “gotten any good vibes yet for our funding.” Nine days later, Bryant wrote back that he was meeting with Freeze “to see where we are in the grant request” and, if Freeze said no, “We may have to go to Legislature in January and get language in a Funding bill. I also know how to make that play.” He added a football emoji and wrote “Keep the faith.”

Favre checked in again Nov. 5: “I know it’s Election Day and you are probably busy,” he wrote, but what about the funding? Bryant had endorsed fellow Republican Tate Reeves to replace him.

Favre wrote to Bryant: “If our guy wins I’ll feel better about things but if the other guy wins I feel like Nancy and I can forget our vision for Southern Miss.”

Bryant wrote back: “That’s one reason I have been pushing Tate so hard. He has to win. Then we set up a meeting on Wellness center at USM.”

Reeves beat Democrat Jim Hood by 5.08 percentage points. But whether Bryant actually intended to set up another meeting or was just telling Favre that, he was stuck.

On Nov. 11, Bryant texted Freeze:

“Brett Farve [sic] keeps asking about the project. I told him a number of times it would be January before we would know anything. Apparently he was assured by Nancy it would be funded.”

Freeze sent Bryant dates when grant proposals would be submitted. Bryant replied: “Can I send that to Brett?” Freeze said it was public information.

Then Freeze asked Bryant: “Should I ask you how strongly you feel about the project?”

Bryant’s response: “I am a supporter and I think it can be a big help to a lot of people.”

Freeze wrote back: “Ok.”

In mid-December, Bryant promised Favre, “We are working on it for sure.” But Shad White and his agents were circling above them. When MDHS drew up plans to award more money to MCEC, White stepped in.

On Dec. 27, White sent Freeze a letter warning of “potentially serious findings” regarding MCEC spending. With his investigation still open, White did not share details. But he warned Freeze that awarding more money to MCEC could trigger a massive financial penalty: “I feel it is imperative to alert you to the severity of this issue.”

On Jan. 9, 2020, New texted Bryant: “Unfortunately, we are going to have to stop all of our services funded by DHS as we have exhausted all monies just trying to hold on. I will need to have my leadership lay off around 60-73 people. Also we will need to start closing our family first centers across the state by next week. DHS already owes my organization a huge amount of reimbursement from the previous contract. I can’t borrow any more money to hold on.”

Bryant played dumb: “Let me see what I can find out.”

He “already knew the answer,” his attorneys would later write in a filing: “Bryant had instructed Freeze to cease further funding of MCEC.”

At the same time, Bryant appeared unconcerned White would discover his involvement in the Prevacus deal. Two days after Bryant became a private citizen again, Prevacus CEO Jake VanLandingham texted him, offering stock. VanLandingham described it as “a company package for all your help.”

Bryant wrote back: “Sounds good. Where would be the best place to meet? I am now going to get on it hard.”

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

On Feb. 2, Favre stood on the field before the Super Bowl wearing a maroon sport coat, enjoying another compliment in a life overflowing with them. The NFL had named him one of the 100 best players of its first century. As he waved to fans alongside other legends in South Florida, Favre apparently did not realize that back in Mississippi, Phil Bryant was selling him out.

In late January, Bryant had checked in with Southern Miss president Rodney Bennett: “Brett keeps asking to help him fund the Volleyball Facility.”

Bennett wrote back: “Governor!!! It’s so good to hear from you- we miss you! … I’ve asked Brett to not do the things he’s doing to seek funding from state agencies and the legislature for the volleyball facility. As you know, [institutions of higher learning have] a process of how we request and get approval for projects and what he’s doing is outside those guidelines. I will see for the “umpteenth time” if we can get him to stand down. The bottom line is he personally guaranteed the project, and on his word and handshake we proceeded. It’s time for him to pay up- it really is just that simple.”

Bryant wrote back: “That’s was my thoughts. Maybe he wants the State to pay off his promises. Like all of us I like Brett. He is a legend but he has to understand what a pledge means. I have tried many time to explain that to him.”

On Feb. 6, at 10:20 a.m., Favre wrote to Bryant: “Governor have you spoken to Tate? He said he was gonna get with his team and figure something out.”

Bryant texted back with a link to a Mississippi Center for Public Policy story headlined:

Largest public embezzlement scheme in Mississippi history uncovered

The story said White had arrested John Davis, Nancy New, Brett DiBiase, Zach New, MCEC accountant Anne McGrew and a low-level MDHS employee named Latimer Smith, who would later have charges dismissed. The last line of the 10-paragraph story: “The [News] allegedly used TANF funds to invest in a pair of medical device companies—Prevacus and PreSolMD—based in Florida.”

“This has been the problem,” Bryant wrote. “Not sure what funding will be available in the future.”

Favre told Bryant he was “well aware of it.” But he was still hoping for a “bond bill” to finish paying for the volleyball facility.

Shad White would say publicly he was alerted to the fraud by a whistleblower:

Former Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant.

After all, Bryant had told White that John Davis was funneling government money to the DiBiases, triggering the inquiry.

White almost certainly did not know the trail would lead to Bryant. But during the course of the investigation, law enforcement found explosive texts implicating Bryant and Favre that eventually became public.

The last three years have brought a web of criminal cases, civil suits and PR moves. MDHS is suing to get its money back, even though its director at the time requested most of the misspending. Seven people have either pleaded guilty or now face criminal charges, including Nancy New, who pleaded guilty to four counts of bribing a public official, two counts of fraud against the government, six counts of wire fraud and racketeering. Her schools closed. Her reputation is shot. So is Christi Webb’s.

White would list $94 million in “questioned costs in” a report, which spawned a flurry of headlines and news stories about Mississippi’s “94 million embezzlement scandal.” Pigott, the former U.S. prosecutor who was hired by MDHS to track down the money, puts the number at “at least $25 million.”

The biggest chunk, by far, went to Favre’s projects: $8.3 million.

Pigott has said publicly that Tate Reeves fired him for trying to subpoena the USM Athletic Foundation. Reeves countered that he did it because Pigott had “a political agenda.” White, who has been dogged by insinuations that he was protecting Bryant, tweeted, “Firing Pigott is a mistake.”

But if Reeves was trying to keep the scandal from reaching Phil Bryant, he failed to convince an important constituency: federal prosecutors who continue to investigate the case.

Plea deals have come slowly but steadily, each one a domino leading to a more important one: New’s accountant, Anne McGrew (October 2021); Nancy and Zach New (April 2022); John Davis (September 2022); and, in March, Brett DiBiase and Christi Webb. All are awaiting sentencing except Davis, who was sentenced to 32 years in state prison but will likely see that reduced significantly. In April, prosecutors indicted Teddy DiBiase, who is, at least for now, fighting the charges.

There is no guarantee that Favre will be indicted, but he is one of only a few potential dominos left. Jake VanLandingham is another. The last one, presumably, would be the biggest of all: Phil Bryant.

“In complex fraud prosecutions, it’s not uncommon for the government to work their way up the ladder, using cooperation to try to build their case,” says Belmont University Law professor Lucian Dervan, an expert in both white-collar crime and plea bargaining.

In a subtle but revealing indication of how serious the government considers this case, recent indictments were co-signed by Glenn Leon, the chief of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Fraud Section, and Brent Wible, the chief of the DOJ’s Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section.

The DOJ declined to comment on any aspect of the case. Prosecutors considering whether to pursue Favre may be weighing the chances of convicting a local hero vs. the optics of not charging one and whether they would need Favre’s help to get Bryant. Herschmann, Favre’s attorney, has already given hints at a legal defense: Favre, who was not employed by MDHS or MCEC, did not know this was welfare money; the $1.1 million for promotional work was legal and unconnected to the volleyball deal; and taking money from one government entity (MDHS) and giving it to another (Southern Miss) is not embezzlement anyway. Herschmann told CBS that Favre did not question whether the Prevacus funding was legal because he trusted Bryant.

Bryant has defended himself aggressively. Though the former governor indicated he would accept Prevacus stock, he either ran out of time or suddenly changed his mind before the arrests. He told Mississippi Today, “I never asked for, received, or wanted stock in that company.” By April 2022, both of Joe Canizaro’s companies had stopped listing Bryant as an officer.

MDHS is suing the people who received state money improperly. Bryant’s lawyers have fought hard to avoid turning over his text messages in that case; his texts in this story came originally from other people’s phone records. Bryant claimed to release all relevant texts May 4, at Bryanttexts.com, but that was met with skepticism. On May 5, Judge Faye Peterson decried “the parties[’] proclivity to speaking to the media before and/or without presenting matters to the court” and issued a gag order for everyone connected to the civil case.

Most lawyers contacted by SI declined comment on behalf of their clients, citing the gag order. But through his attorney, Chuck Mullins, Davis told SI, “I'm embarrassed I succumbed to the powers above me and which had been in place years before me. That's not an excuse. I deeply regret my actions.”

The public has still not seen texts between Bryant and Davis as the scheme unfolded—but those could come out in a criminal trial.

Bryant’s lawyers have argued in a court filing that New and Davis embezzled MDHS funds “unbeknownst to Bryant.” They have said Bryant didn’t know the money Favre wanted came from TANF, because Favre never mentioned it. When Mississippi Today’s Wolfe asked Bryant in April 2022 about Favre and New, he said, “I just did not know that they had a relationship.”

Favre claims to not know it was a scheme at all. No texts have emerged in which he acknowledged, or was directly told, that the money was intended for needy families. Herschmann told conservative media outlet The Blaze in February that “Brett Favre got money from a not-for-profit. He had no idea, no one claims he did, nor would he have any idea, any way of knowing, where the not-for-profit got its money.” But Favre met repeatedly with John Davis, the state welfare chief. When Bryant fired Davis, Favre told the governor, “I love Nancy New and John Davis. What they have done for me and Southern Miss is amazing.”

Favre has tried and failed to remove himself from MDHS’s civil suit. He has sued everyone from White to talk-show hosts Pat McAfee and Shannon Sharpe for defamation (he recently withdrew his suit against McAfee). Favre reached an agreement with the state to repay the money that was paid to him personally, but not the money that was supposed to cover his promise to Southern Miss or what went to Prevacus. Southern Miss opened the indoor volleyball facility for the 2020 season. As for the final cost and who paid it: Before the gag order was issued, the university declined to answer questions, citing “pending litigation.”

Favre’s attorneys recently introduced a “donor agreement” that shows he promised to pay no more than $1.476 million, Mississippi Today recently reported. But the agreement is dated May 2, 2018—after the university had received $5 million in the lease and, presumably, at least some of the $1.1 million Favre was paid for promotional work.

Favre has also decried coverage of the scandal, saying, “I have been unjustly smeared in the media. I have done nothing wrong, and it is past time to set the record straight.”

Anyone can blame the media in a press release. It’s not so easy under oath.

Now go back to early 2020. The state welfare director who sent millions to Favre had been arrested. So was the woman who served as Favre’s direct contact for three years. So was her son. The media was calling this a massive embezzlement scandal, and the governor told Favre this was why he would not receive any more funding.

If Brett Favre believed he was innocent, how would he react?

Would he feel shocked?

Betrayed?

Angry that nobody told him he was getting welfare money?

Embarrassed to be associated with accused felons?

One month after New was arrested, Favre contacted her. By this point, New had finally hired an attorney. But she was still deciding whether to cop a plea—and, presumably, testify against her coconspirators.

Favre texted New:

“Deanna and I want you to know that we are thinking about you and praying that all is well.”