It was the summer of ’68 and I was a 13-year-old kid from Northern Ireland visiting cousins who had emigrated to the United States. We were driving down the forest highways of north Virginia listening to the news of the student protests on the streets of Europe, Paris in particular, when a tail item grabbed our attention: there had been protests too on the streets of Ulster.

A new so-called civil rights movement had staged a march calling for fairer treatment of Catholics in a society dominated by the Protestant majority. My parents exchanged concerned looks. I was interested but not overly concerned. None of us knew that within six months, by January 1969, the discontent would have intensified into a fully fledged conflict that would become little short of a civil war. Over the next three decades it would claim more than three thousand lives – including two of my schoolmates.

Over the months between August and January, the civil rights movement escalated. No longer a tail item on the news, it came to dominate the background to our lives, as loyalists fought back and eventually the police joined in. This was supposedly to keep the peace but the Royal Ulster Constabulary, far from neutral, used force exclusively against the Catholic demonstrators. It was the beginning of January 1969 when things really took off.

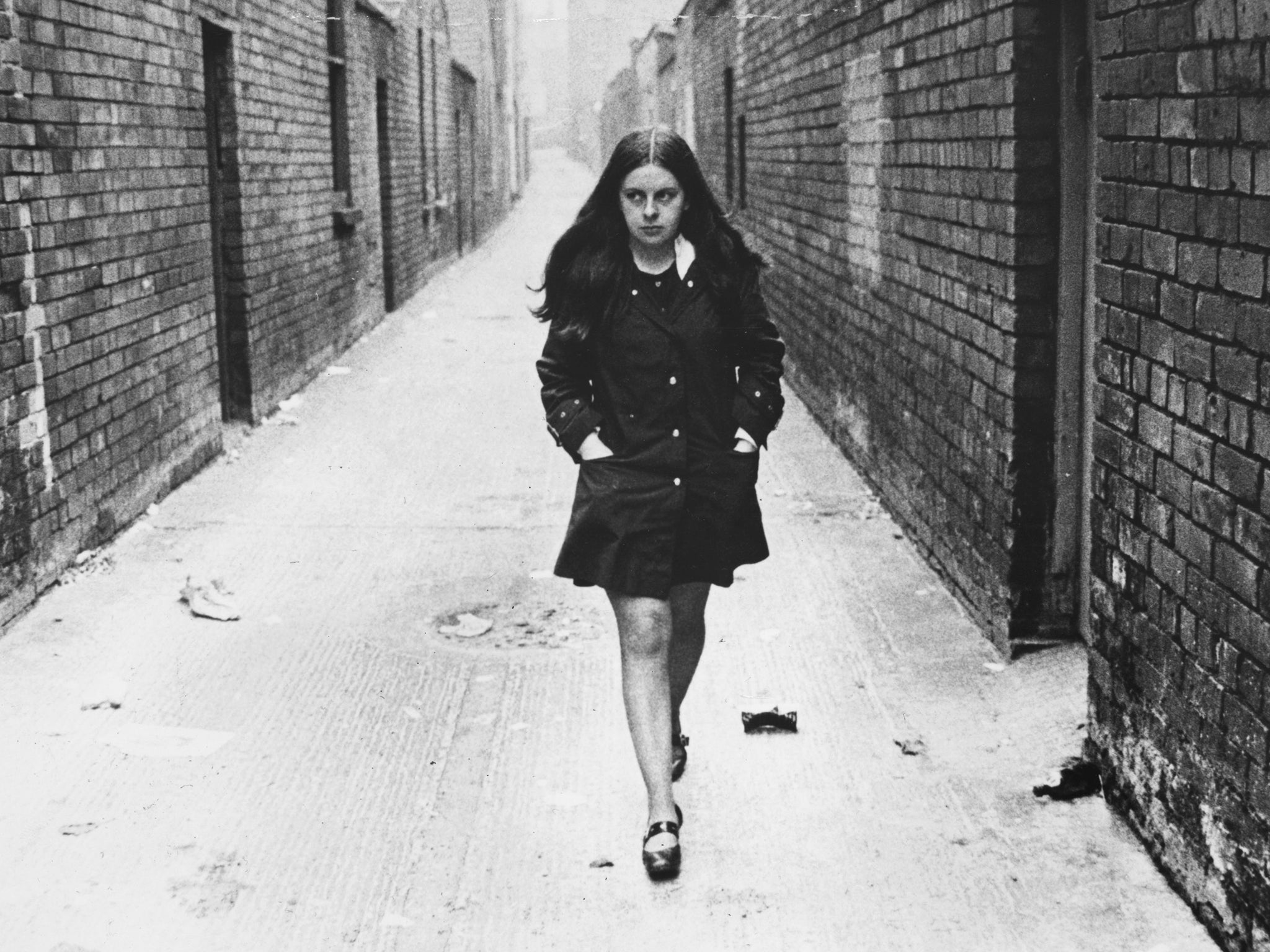

A group of students from Queens University Belfast had formed an organisation called the People’s Democracy, to fight – on good old idealistic student grounds (the Paris riots had left their mark) – for equal treatment of everyone in Northern Ireland.

“One man one vote” was still an issue there. A relatively affluent member of the Protestant ascendancy, my grandfather owned two buy-to-let properties in Derry (or Londonderry as he would have insisted on calling it) and had a vote in local elections for both properties, as well as his personal vote. Non-property owners could vote for Westminster but not for Derry city council. This deliberate gerrymandering had led to the artificial construct that Northern Ireland, designed to be pro-union with Britain, was by definition largely Protestant.

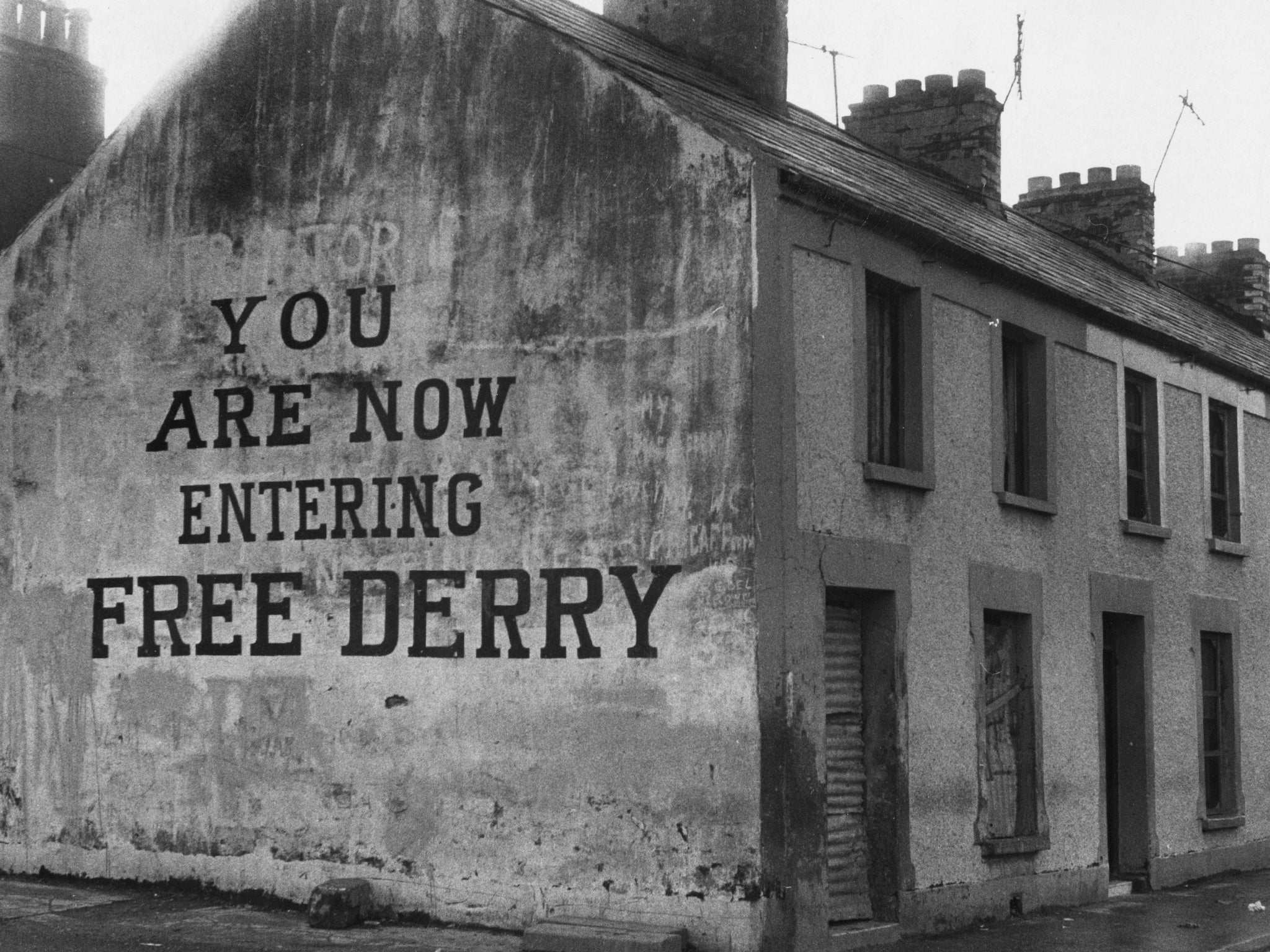

The gerrymandering had become social as well as political. Most Catholics rented privately or lived in social housing which in turn meant that Derry, a majority Catholic city, was run by a Protestant minority. A further poignancy came from the fact they mostly lived within the 17th century city walls looking down on the Catholic housing estates camped below them in the Bogside. These were the exact positions the opposing forces had occupied during the siege of 1689, after which the Protestant victors had renamed the city Londonderry to reinforce their political attachment to England.

The People’s Democracy march in January 1969 was to take four days from Belfast to Derry, but en route at Burntollet Bridge – in an incident which has come to symbolise the beginning of the Troubles – they were ambushed by a loyalist crowd. This included off-duty police officers wielding iron bars, bottles and bricks. They were attacked again on the outskirts of Derry and later that night RUC officers – who were supposed to keep the peace – decided to restore the “status quo” and ransacked the Bogside, damaging homes.

To protect themselves, the locals erected barricades in the streets and renamed their area Free Derry. The lines had been well and truly drawn.

Over the months that followed I sat at home in bourgeois Bangor, a mostly middle-class seaside resort largely immune to the sectarianism, and watched with horror on television as the violence spread across most of the rest of the province. Loyalist militia sabotaged utilities in Catholic districts. A rash of bombings took place, most blamed on what had been an old ghost long thought slain: the IRA.

In fact many were conducted by Protestant gangs, but by invoking the ghost they had brought it back to life. And in a new, more deadly form. The old IRA, which had caused relatively minor incidents in the 1950s, had retreated to peaceful socialist politics which now seemed irrelevant. In the place of this official IRA emerged a new Provisional IRA (nicknamed the Provos) who declared violence was the only response to the increasingly one-sided attacks by the RUC.

That summer, the loyalist community began its annual summer celebrations of the 1689-1690 battles, in which Protestant English forces defeated their Catholic King James II on Irish soil in favour of King William of Orange. The police protected them against jeering stone-throwers who regarded this as a celebration of their continuing subjugation. In Derry, it ended with a two-day Battle of the Bogside, in which the police used water cannon and CS gas against the protesters.

The parades continued. Back in sunny Bangor I went with added interest for once to watch our local parade as “King Billy”, drunk as usual, swayed on his white horse in time to the martial tunes played on pipes, horns and frightening giant Lambeg drums – once used to summon Protestant settler men to confront Catholic natives who had lost their land. Now the ghoulish cries were issued more virulently than ever: “We’re up to our necks in Fenian blood, surrender or you die, for we are the Billy, Billy boys!” For the first time I felt not just an involuntary surge of adrenalin, I felt my stomach churn. Even Bangor suddenly seemed not so safe.

As I entered the second half of my teens, the war waged on, ever bloodier. The RUC’s heavily armed paramilitary wing, the B-Specials, was disbanded, but the RUC carried on. Unlike the rest of the UK we had never had unarmed policemen. It said enough that Northern Ireland did not have “police stations” but “police barracks”, and these were now encased in high wire enclosures often behind concrete walls. Concentration-style camps were established for – mainly IRA – suspects interned without trial. Paramilitaries on both sides spawned criminal gangs. In a rare shopping trip to Belfast I was threatened with “kneecapping” by a member of the Shankill Tartan, a band of loyalist thugs and muggers.

Following the resignation of Northern Ireland’s prime minister, the abolition of his Protestant-dominated government at Stormont and the collapse of public order, Westminster took control and sent in the army. At first welcomed by the Catholic community, the army was soon identified with the British-run, unionist status quo and morphed into the enemy. The outside world saw the conflict as Catholic versus Protestant but on the ground it emerged as it had always really been: those for a united Ireland against those preferring the British identity that had given them privileged rights for so long. A long-standing identity crisis became a civil war.

The bombing and shootings increased, with British military and civilian targets on both sides considered fair game. Bangor was not excluded. The windows of Fealty’s pub, which attracted a mixed crowd but favoured an Irish identity with regular folk music evenings, had its windows shot in and several were injured.

Just weeks after my 15th birthday I found myself lying on the bedroom floor in the middle of the night. My mother rushed in to see if I was all right. I was, if somewhat puzzled. “The IRA have blown up Main Street,” she stammered. From half a mile away I had been blown out of bed. A pair of car bombs had demolished nearly all of the street including the Co-op department store which had been a favourite teenage meeting point.

In Derry, ever the epicentre, anti-British protests had escalated to the point where in January 1972 British parachute troops fired live ammunition into an angry crowd, killing 13 (a 14th died later). The same number were injured. The event known as Bloody Sunday became yet another pivotal point on the downhill slide to anarchy. An initial investigation vindicated the troops who claimed they had fired on would-be bombers. The result was a recruitment surge for the Provos. A reassessment was only undertaken as part of the 1998 Belfast agreement and took until 2010 to establish that the soldiers had lied and behaved “recklessly”. The deaths were reclassified as murders.

On another rare shopping trip to Belfast I found my Marc Bolan-style tousled hair filled with broken glass after a bomb blew out pub windows only yards away. I was 18 with an offer from Oxford. It was an easy choice. I was “outta here”!

Not all my friends were so lucky. A fiercely bright kid called Tim (to my shame I forget his surname) went to Queen’s, as I had once planned, and was killed by a bomb planted in a Belfast bar near the university. Another friend, Johnny Marsh, joined the still extant RUC and was shot dead in an IRA ambush. Years later I met his brother who had joined the Hong Kong police and was returning home after the handover to China: “I’m taking my gun with me, Peter,” he confided.

In the years that followed I returned rarely, mostly as a reporter, and most scarily to interview Billy Wright, a confessed loyalist terrorist sought for a dozen murders. He was later caught and interned, only to be shot dead in prison.

The first glimmer of hope came in the early 1990s, when there were talks about talks, rumours about secret contacts at the highest level, suspicion that somehow, somewhere the unthinkable might happen: there might be an end in sight. In 1994 I was sent to report on new secret developments, for which I was given closed door access to John Major in Downing Street and managed peripheral talks with Sinn Fein.

It took four years for the Good Friday Agreement to emerge. It was an agreement to differ. Both sides were allowed to pretend they had won; although both knew they hadn’t really. What they had agreed was a “transition phase” without any decision on what came after, and the hardline DUP were determined there would be no “after”.

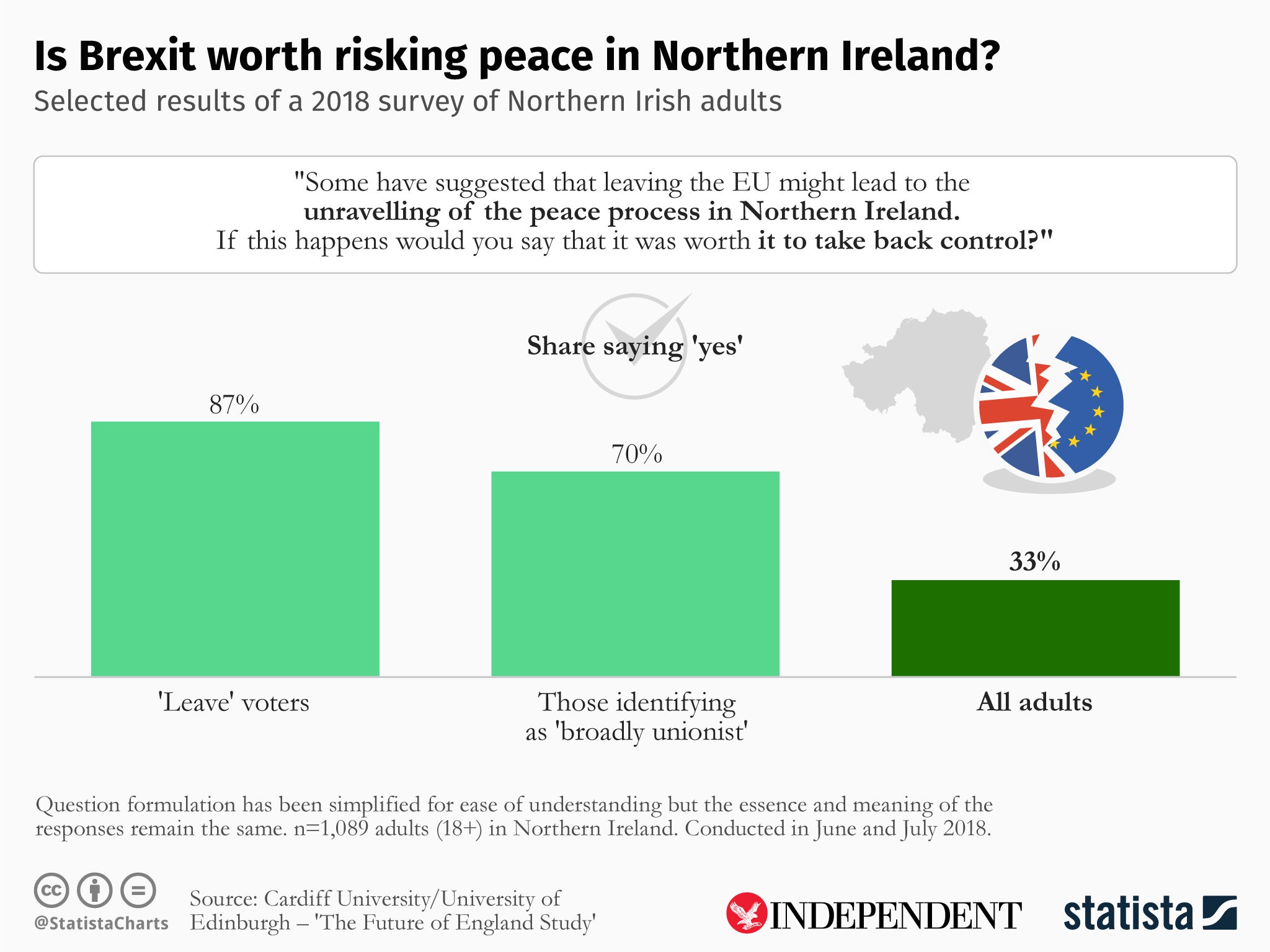

It was a “wait and see” agreement in which everyone agreed to keep their eyes closed. Now Brexit is forcing them open.