The fierce windstorm that walloped this small defunct port in late spring stunned even a local ecologist long resigned to the devastation wrought by the disappearance of the once ample Aral Sea.

A thick, stinging haze greeted the ecologist, Gileyboi Zhyemuratov, as he stepped outside that day in May. “When you opened the door, everything was white like snow,” says Zhyemuratov, 57, a descendant of generations of fishermen in a place where there are no longer any fish.

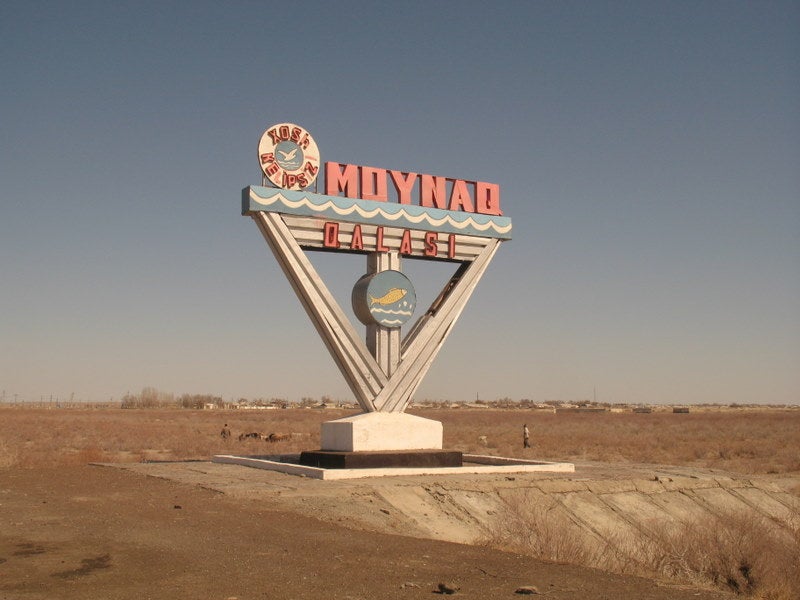

For three days, the tempest hurled silt off the former seabed of what was once the planet’s fourth largest inland body of water. It blotted out the sky and left the residents of the former port, Muynak, in western Uzbekistan, chewing salty grit. Even the rain turned brackish, sending panicked farmers scrambling to rescue crops.

As the storm blew in, Vladimir Zuev, a retired Russian pilot turned tour operator, was sitting beneath his shady pergola, where the garden gnomes consist of a bust of Lenin and other Soviet icons.

“It was impossible to see,” he says. “The salt was dry, yet it adhered to the skin and was difficult to wipe off. You could barely wash it off with water.” The flowers in his garden withered.

Paradoxically, the man-made disaster strangling the town has become its main attraction in recent years. Tourism is booming.

“A lot of people want to see an ecological crisis,” says Vadim Sokolov, head of the Uzbek branch of the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea.

Where waves once lapped at the harbour’s lighthouse, rusting trawlers now sit abandoned on the sandy seabed far below, like dinosaur bones bleaching in the sunshine.

A selfie from the ship cemetery has become a must-have for the Instagram crowd.

Ali and Poline Belhout, a Parisian couple in their 30s, stopped in Muynak on their yearlong around the world tour. “It is sad to see that some years ago there was a sea, and now it is only a graveyard for ships,” she says. “To see boats docked like that is a little freaky.”

Once lacking a hotel, Muynak now has three, along with an internet cafe, and the government is organising an electronic music festival here on 14 September.

The sea, which vanished from Muynak around 1986, is now more than 75 miles away. The only water view is in the modest local museum, with its tattered photographs and nostalgic oil paintings of the once blue horizon.

That unprecedented storm last May confirmed a grim prognosis: the environmental fallout from the loss of the Aral Sea is intensifying.

The sea’s disappearance “is not just a tragedy, as many people say, it is an active hazard unfolding before our eyes,” says Helena Fraser, head of the United Nations Development Program in Uzbekistan.

The Aral Sea problem is not new. The five states of central Asia first established the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea, or IFAS, 25 years ago, though they refuse to cooperate on key problems like water distribution.

That has long stymied any solution, along with dubious, Soviet-style agricultural methods and the quixotic quest for a mega-project that will magically restore the sea.

Antique central planning determines what crops are cultivated, says Yusup Kamalov, chairman of the Union for the Protection of the Aral Sea and the Amu Darya, one of two rivers that feed the sea. Instead of drip irrigation, mostly outdated techniques consume 80 per cent of the available water.

“We are still in Soviet times in terms of farming,” Kamalov says. “That is why I am not expecting changes.”

The roots of the problem go back around 60 years, when Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev decided to industrialise agriculture across central Asia despite its aridity. The Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers were diverted into thirsty irrigation canals that fed wheat and cotton fields.

By the time the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the Aral Sea was already retreating. Even though the existing water distribution numbers were strangling it, the countries of central Asia signed an agreement to lock them in place.

Both Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan still grow cotton, even as a push against forced labour to harvest the crop in Uzbekistan and the shrinking water supply have led to a reduction in cultivation.

Climate change has also intensified the scarcity of water. The glaciers in the mountains of Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan that feed the two rivers are shrinking.

Of all the water that flows into the Amu Darya from the Pamir Mountains, less than 10 per cent reaches the Aral Sea. The parched sea, now shrunk to around 10 per cent of its original surface area, is 95 feet shallower and so brackish that it no longer supports fish or much life.

On a recent trip to Muynak, some international experts gasped as their bus crossed a bridge over the Amu Darya river because only a thin, weary stream struggled through the wide, sandy riverbed.

Yet along the road, rice fields were flooded with water despite a government directive to grow other crops.

“We can see the problem right in front of our eyes – it is absurd, completely absurd, that they are growing rice here,” says François Brikké of the Global Water Partnership, a water management organisation in Stockholm.

Local governments and farmers tend to disregard the conservation efforts, Sokolov says. When the price of rice doubled on reports that cultivation would be limited, some areas rushed to plant.

Further grumbling erupted at lunch when waiters delivered heaping platters of locally grown rice along with meat – a central Asian speciality called plov.

Boriy Alikhanov, the host and the leader of the Uzbek parliamentary faction from the country’s Ecological Movement, suggested that trying to reform water consumption patterns was as much about changing tradition as agricultural techniques. “It is a cultural problem,” he says.

Before the sea disappeared, Muynak was a thriving port of 25,000 people. Most worked on trawlers or in the bustling cannery. About 20 per cent of all the fish consumed in the Soviet Union came from the roughly 30 species in the Aral Sea.

Aside from killing the fishing industry, the sea’s disappearance spawned a grim array of health problems like lung and kidney diseases and increased child mortality. In addition, without the mitigating effect of the wind blowing across the water, summers are hotter and winters colder throughout the region.

Neighbouring Kazakhstan pulled off the one significant feat towards restoring the sea. It built a large earthen dam in 2005 to contain the waters of the Syr Darya river within a smaller basin.

The dam rejuvenated what is sometimes called the Small or North Aral Sea, with 100 feet of water in places. Fish, having once vanished, now flourish, along with eight processing plants, says Marat Narbayev, deputy director of IFAS in Kazakhstan.

The Kazakh town of Aralsk, at the opposite end of the Aral Sea and devastated like Muynak, might revive as a fishing port with the sea now only about 10 miles away.

If the dream of restoring the full sea has been largely abandoned, experts want to see less water siphoned off the rivers. For that, officials say, the countries of central Asia must engage in the delicate process of renegotiating water distribution and coordinating aid programmes, including the proceeds from a UN trust fund that is expected to open soon.

“The main goal today is to mitigate the consequences of the Aral disaster,” says Alikhanov of the Ecological Movement. “In the modern history of humanity, it has never happened that an entire sea perished in front of the eyes of one generation.”

© New York Times