Robben Ford has spent his career carving out a musical buffer between blues, rock and jazz/fusion. That could be a recipe for slick blandness, but Robben creates something wonderful, combining the best elements of his diverse influences.

"The first blues that I ever heard was The Paul Butterfield Blues Band with Mike Bloomfield on lead guitar," he told us, back when he gave us this masterclass in 2015. "It was incredible how intense it was compared to everything that I’d heard up to that point. It was a revelation, and it gave me my direction to play the electric guitar. I then started buying records just because they were blues records… or jazz. There’s a three-record set called The Blues Box with Jimmy Witherspoon, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, and Lightnin’ Hopkins. I really learned everything I know today about Mississippi Delta-style blues guitar playing from those records.”

When did he start fusing jazz into his blues playing? “After I got out of school, I bought Mickey Baker’s first book on jazz chords and I learned all these jazz chord voicings. I’ve since done my own book called Rhythm Blues, which is my version of the Mickey Baker one, but taking all the information and putting it into a traditional blues format. Within a short period of time, I had an experience where I was playing with Charlie Musselwhite; I was 19 and we were on the same bill with Larry Coryell and his trio in Los Angeles.

"I asked him what all that ‘out’ stuff was that he was playing – the things that I couldn’t understand! And, of course, it wasn’t ‘out’ at all, it was just the diminished scale, the half step, whole step scale. So then I went home, took him at his word and I just went, ‘Half step, whole step, half step, whole step’ within the scale and started messing with it and making up licks with it. I realized that it sounded like Miles Davis’s music to me, so that was a cool revelation and it opened up the world of the II-V-I progression, which is basically jazz in a nutshell. That really helped me and I started being able to expand my harmonic playing.”

What defines good blues playing? “Number one is tone and number two is phrasing," he says. "Blues doesn’t require a lot of harmonic knowledge to deliver its message but it is really a very expressive form of music. It’s meant to tell you something, so what’s important is the sound of the voice and how you say the things you’re trying to say. There are a lot of different styles in the blues, which is really quite incredible. For such a simple form, there are so many different voices.

“For the most part, people just know three chords and the pentatonic scale. That is a box. That is a cul-de-sac! It takes someone like BB King to continue to mine that field. I’m not that guy, but that’s why I opened up my mind to a broader harmonic world and learned chords and scales. That’s how you get out of the rut – give yourself further opportunities and more harmonic and melodic information that you can expand upon. You will see that what you can do and what is possible is limitless.”

One of the best-known aspects of Ford's playing is the diminished scale, which "seems to loom large in my legend", as he jokes. In these examples, we'll work through the concepts that Robben discusses in the video, showing how the diminished scale is closely bound up with the old 12-bar blues progression.

Below is the full video – which we recommend watching before you start the exercises, it's packed with great advice beyond these specific examples – and then with each example the videos should start at approximately the correct place.

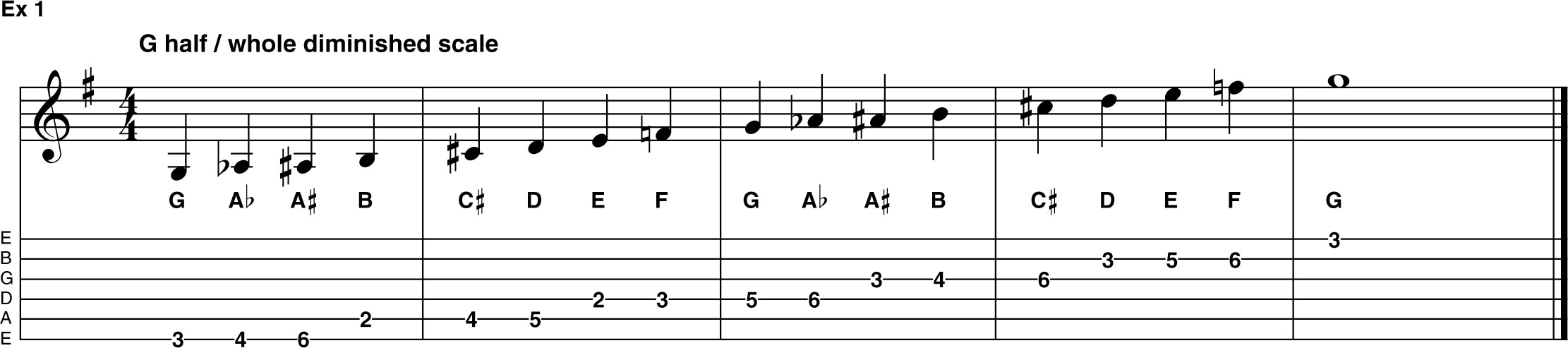

Ex1

First of all, the technical stuff. The diminished scale has eight notes, with alternating semitone and whole tone intervals. You can start with either interval, but the more common half-whole variety is applicable to what we're doing here. Here it is in G.

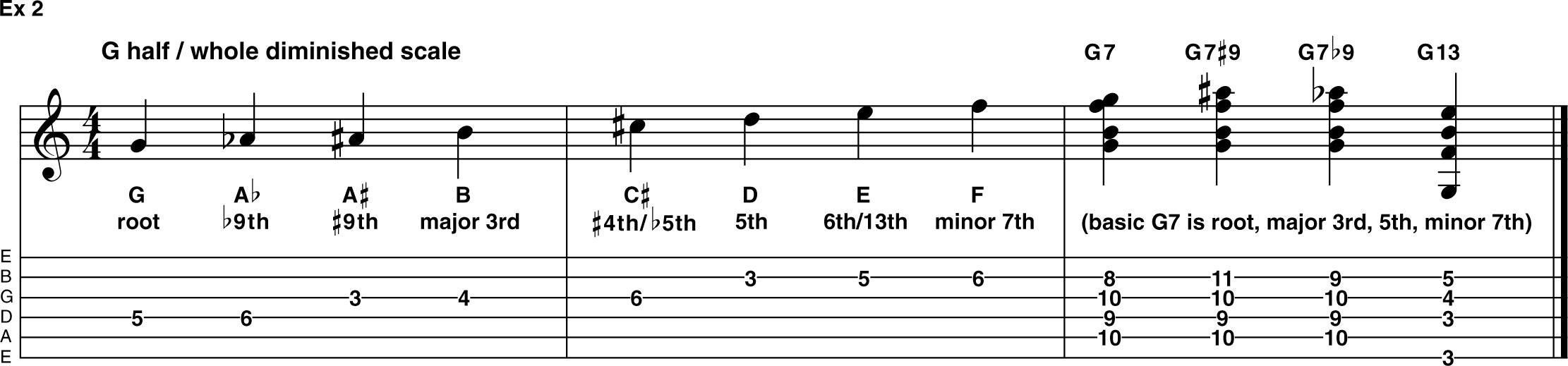

Ex2

It's a strange scale, but it works nicely over a (jazzy) blues in G because it contains so many tasty notes. The b9th (Ab), #9th (A#) and 13th (E) are common extensions added to the G7 chord, and then the C# (or Db) is the tritone, a vital bluesy sound!

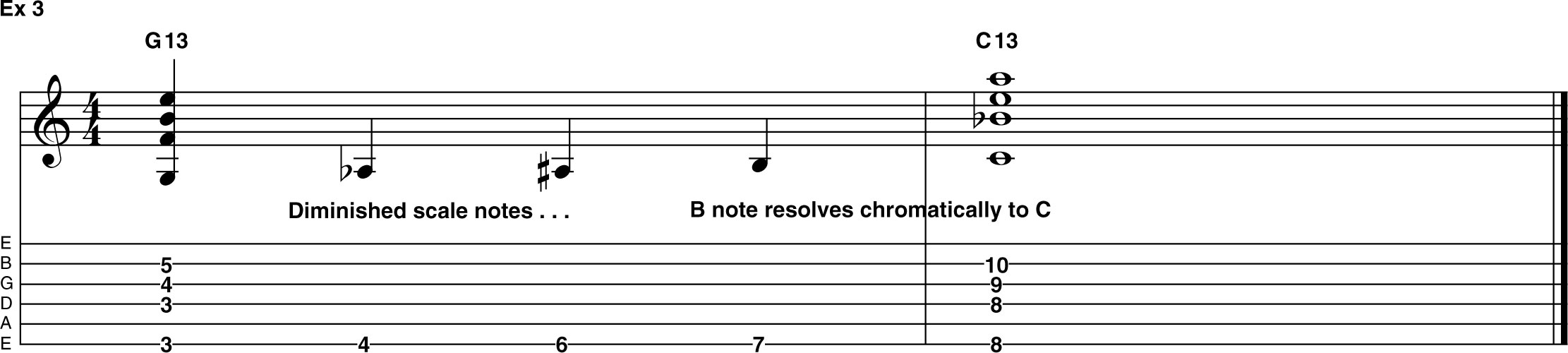

Ex3

Feel free to jam with the scale, but here's what Robben shows us on the video. The B note in the G diminished scale becomes a moment of tension as we await the imminent C7 chord. Moving chromatically to the C note takes us out of the diminished scale, but the urge to resolve to the root note of C7 is more powerful.

Ex3 tab (right-click to download)

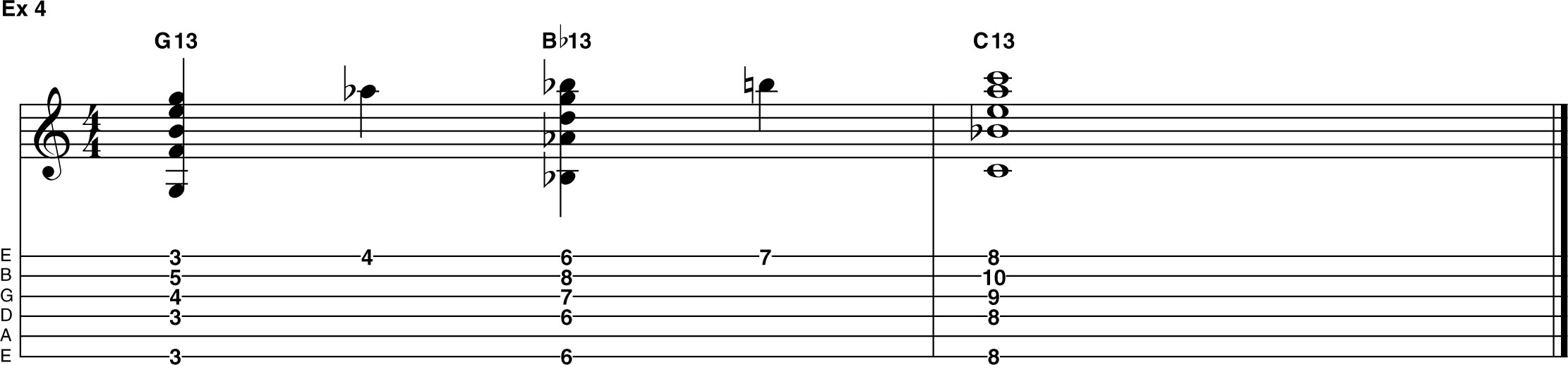

Ex4

Using Bb13 as a passing chord, Robben creates this cool chord-melody change from G to C. Strictly speaking, a 13 chord should also include the 9th, but by omitting it, all of the notes from G13 and Bb13 are within the G diminished scale. Clever!

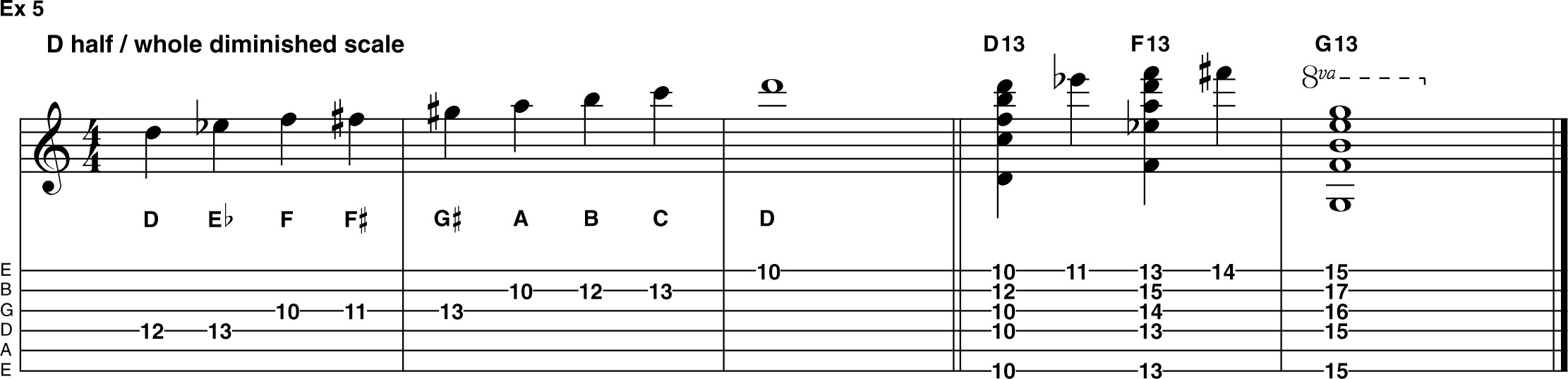

Ex5

Robben prefers not to use this trick with C diminished (C Db D# E F# G A Bb) for the C7-G7 (IV-I) change. There's certainly a different shape to it, without that chromatic resolution. However, he uses it later in the blues progression, for the D7-G7 (V-I) change.

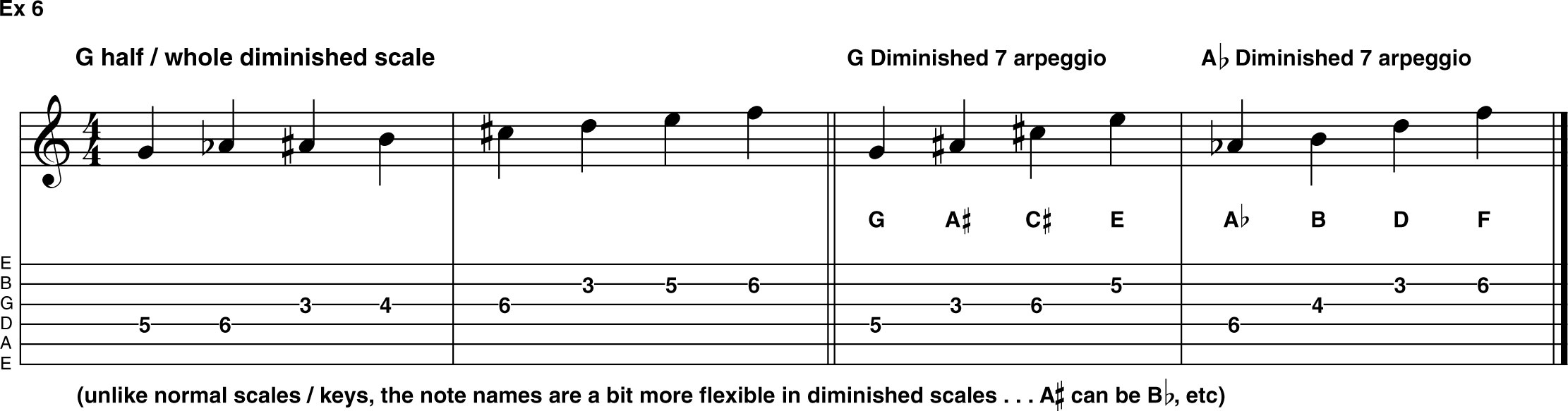

Ex6

People often confuse the diminished scale with the diminished 7th arpeggio, which is basically a stack of minor 3rd intervals (Gdim7 is G Bb Db E). That's not so daft, though; the diminished scale contains two interlocking dim7 arpeggios, Gdim7 and Abdim7 in this case.

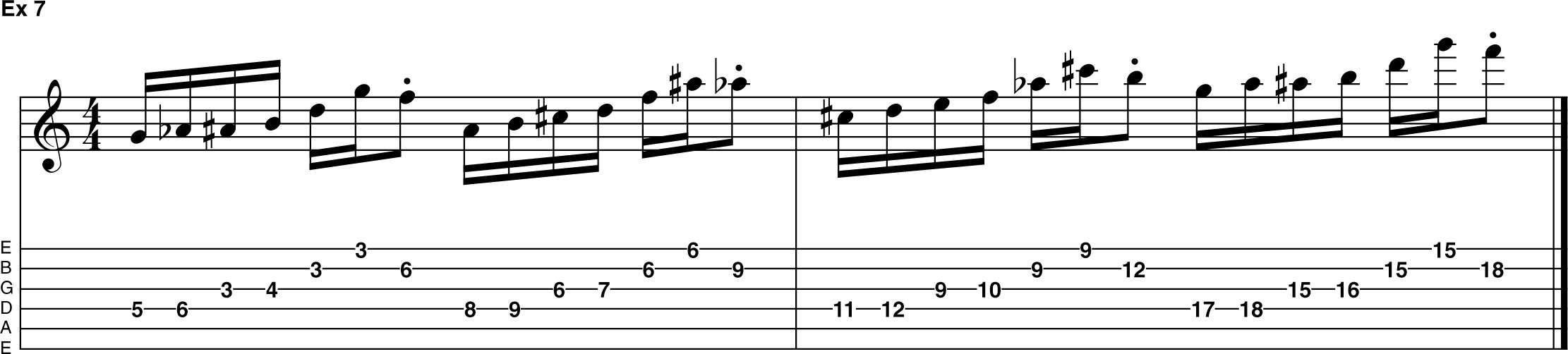

Ex7

And the upshot of that is that every note in the scale is a minor 3rd (three frets) from another scale note. Therefore, any diminished scale phrases or lick can be moved up or down three frets and you'll still be within the scale.

Originally published in Guitarist magainze, 2015.