This story was included in our November 2023 issue, devoted to some of the best writing The Walrus has published. You’ll find the rest of our selections here.

When the wave of reckonings triggered by #MeToo hit the literary world, we became curious about how CanLit, an institution stocked with provocative personalities, would fare. Which major Canadian book would suddenly become difficult to defend post Weinstein? What sprung most readily to mind was Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers, a novel with the distinction of being intersectionally problematic (it’s racist and sexist). The book is particularly canonical in classrooms because its publication is seen as signalling the arrival of postmodernism in Canada, but it is also increasingly disturbing to teach because of its politics. Myra Bloom signed up for the mission of re-evaluating the novel and Cohen’s mystique as a self-styled ladies’ man more generally. The essay, originally published in April 2018, was especially well timed given the hagiolatry that intensified after Cohen’s death, but Bloom’s nuanced insights into the limits of artistic veneration are just as fresh and valuable today. —Carmine Starnino, interim editor-in-chief, November 2023 issue

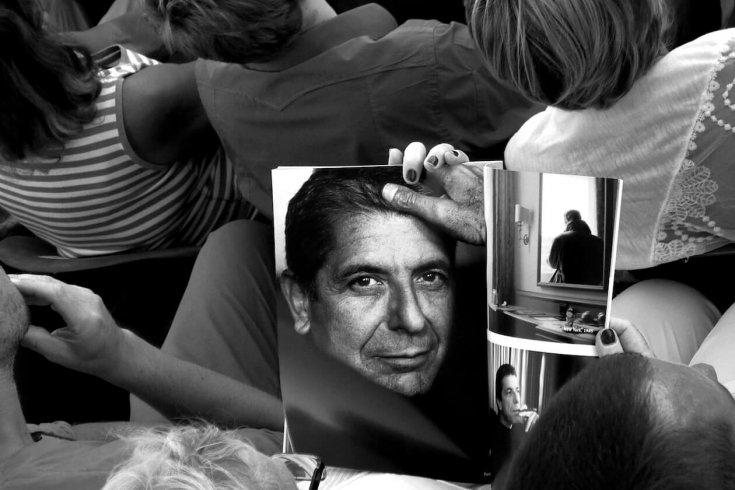

On November 10, 2016, the night Leonard Cohen’s death was announced, pilgrims began assembling at the doorstep of Cohen’s Montreal home to cry, pray, and lay offerings. This was just the beginning. Over the next year, the multitudes would gather to worship at Montreal’s ever more prodigious altars: two enormous murals, one of them twenty storeys high; a star-studded tribute concert; a blockbuster exhibit at Montreal’s Musée d’art contemporain. Today, it’s clear that a full-blown canonization has taken place: as a recent New York Times article perceptively noted, Cohen has become the “New Secular Saint of Montreal.”

The description is not hyperbole or metaphor but an accurate assessment of Cohen’s immaculate status in the current zeitgeist. The former enfant terrible of Canadian arts and letters—erstwhile refuser of Governor General’s Awards, ingestor of drugs on Greek islands, recipient of head on unmade beds—has transmogrified, through death, into a holy figure. The posthumous hagiography attests to the power of Cohen’s religious imagery, which arguably reached its peak in his final album, You Want It Darker. The haunting title track, featuring backing vocals by the Shaar Hashomayim Synagogue Choir, makes you feel like Cohen is in direct communion with God as he proclaims, in the Biblical tongue of his ancestors, “Hineni, hineni / I’m ready, my Lord.” Add to this the massive success of “Hallelujah”—ignored when first released in the ’80s, resurrected by Jeff Buckley, Rufus Wainwright, and k. d. lang, and currently in contention for the most overperformed song in history—and you’ve got yourself a prophet.

Such is the aura of sacredness that attaches to the High Priest of Pathos that dissident views are treated as heresy. Writer and critic Anakana Schofield said it best in an essay published a month before Cohen’s death: “Be very careful challenging opinion on Leonard Cohen, it’s like bringing up someone’s ex-partner with a mistaken warm smile on your face.” Full disclosure: as the child of two Montreal-raised Jews (one of whom is, incidentally, a Leonard), I’ve been steeped in Cohen’s music/legend since I was a zygote, and my love for him abides. Still, I think it worth considering how the posthumous focus on the “later” Cohen—whose grandfatherly, fedora-clad image towers benevolently (in duplicate!) over Montreal—obscures a more complex understanding of a man who, before he became divine, was obsessed with the flesh, and not always in ways that are palatable today.

Given that our threshold for bad male behaviour is currently sitting at an all-time low, we can surmise that Cohen’s “ladies’ man” persona—cultivated in an era when the term still connoted “romantic artist” rather than “pickup artist”—would get less traction now. By his own admission, Cohen was never “very good” at relationships: “I had a great appetite for the company of women,” he said in a 2005 interview. “[But] I wasn’t very good at the things that a woman wanted” (read: fidelity). In his work, women are often depicted as muses—quasi-mystical figures who inspire the poet’s imagination and then conveniently disappear (cf. songs such as “Hallelujah,” “Suzanne,” “So Long, Marianne,” “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” . . . ). On the first page of his 1994 biography, Leonard Cohen: A Life in Art, Ira Nadel notes approvingly: “when entrapped by beauty, [Cohen] finds his art imperiled. He responds by seeking freedom, recognizing the need to dismantle love . . . for only art can truly seduce Leonard Cohen.”

This is a classic example of what historian Martin Jay calls the “aesthetic alibi” men have been using since the nineteenth century to justify bad behaviour. Today, the myth of the male genius has come under fire in the wake of movements such as #MeToo and Time’s Up, which have established the role of such tropes in legitimating the abusive treatment of women. This isn’t to suggest that Cohen’s dalliances were always so well received back in his heyday; just before Death of a Ladies’ Man (1978) was published, Chatelaine ran a piece called “Death of a Ladies’ Chauvinist,” which wondered whether the book would be a “rejection of his former womanizing self.” One would think that we would be hearing more of this criticism applied retroactively. For some reason, though, Cohen’s womanizing seems to have been grandfathered in. A commemorative 2016 CBC Music profile gushed, “What woman wouldn’t be flattered to be the focus of such a fiercely artistic, intellectual, romantic man?”

In terms of the objectification of women, Cohen’s songs (even the cringe-inducing, though admittedly rollicking, “Don’t Go Home with Your Hard-On”) are nowhere near as extreme as his fiction. This fact has not gone unremarked by the generation of undergraduates currently grappling with his two published novels, The Favourite Game (1963) and Beautiful Losers (1966). The latter, in particular, has long been a staple of CanLit syllabi; its experimental form, along with its critique of history, religion, and other metanarratives, makes it a perfect object lesson in Canadian postmodernism. Lately, though, the book has started to resemble a how-to guide for writers who want to tank their literary careers. Indigenous appropriation? Check. Misogyny and graphic sexual violence? Check.

Beautiful Losers has always shocked readers. Toronto Star critic Robert Fulford famously called it “the most revolting book ever written in Canada” (though, to be fair, he also called it “the most interesting Canadian book of the year”). But where cultural artifacts that are shocking in their own era tend to become less so over time, Beautiful Losers is one of those rare books that is more outrageous now than when it was first published. The narrator (unnamed, though I’ll follow Cohen scholars in referring to him as “I”) is “a well-known folklorist, an authority” on an Indigenous tribe he refers to throughout the novel as “the A— —s.” Today, this premise alone would be enough to warrant a terse rejection letter from potential publishers.

It gets worse: when the book opens, I’s wife, an A— — woman named Edith, has just died by suicide in a baroque manner involving an elevator shaft. This is but one of the many abuses Edith will endure over the course of Beautiful Losers, in which she will also be raped twice, first by a gang of men and then by a possessed vibrator. The narrator recounts these events with gleeful precision and essentially spends the rest of the book “touching her perfect body with his mind.” The novel’s other Indigenous character does not fare much better. I’s erotic attention falls equally on Catherine Tekakwitha, a seventeenth-century Mohawk woman who converted to Christianity and later became a saint: “I fell in love with a religious picture of you,” he announces; “You were standing among birch trees. . . . God knows how far up your moccasins were laced.” Said moccasins are removed in a later scene where a lecherous priest molests her feet—recounted with a stomach-churning “Gobble-gobblegogglewoggle. Slurp.”

It is not surprising, given the above (to say nothing of the ubiquitous masturbation or the fact that the novel’s middle section is penned with “one hand on a letter and one hand up a juicy cunt”), that Beautiful Losers has been going through a bit of an identity crisis of late. In the ’70s, the famous academic Linda Hutcheon named it “the most challenging and perceptive novel about Canada and her people yet written.” In contrast, Schofield recently called it “a failed, fossilized encounter” and “prayed privately that no indigenous woman would ever have to suffer reading [it].” The book’s status in the CanLit canon, formerly unquestioned, also seems less secure these days. One literature professor I polled said he doesn’t teach the book anymore because “there are too many issues to navigate in it.” Another decided to put a trigger warning on his syllabus, cautioning “[s]tudents who ‘love Leonard Cohen’ when they enter the course” that they might be “shocked to find some of his works ethically repellent.” This proved true: a lot of his students, he told me, were indeed deeply offended, particularly by the treatment of Edith.

While such reactions are fully understandable, it is worth looking a little closer at what Cohen was trying to do in Beautiful Losers. We can glean enough from Cohen’s life and writing, including the novel, to know that he did not endorse violence against women in general or Indigenous women in particular. You could even go as far as to say that he was ahead of his time in acknowledging Canada’s colonial history before this issue really entered mainstream consciousness. The book about Catherine Tekakwitha that apparently inspired the novel was in fact lent to him by Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin, a friend of his; according to scholar Randolph Lewis, many elements of Edith’s character, including the abuse, are linked to Obomsawin. Lewis argues, echoing a common interpretation, that “Cohen imagines the Native female body as a symbol of political conquest in his surreal allegory of intercultural violence.” In other words, Cohen is being ironic. You can see it in I’s use of a nationalistic explanation to explain Edith’s rape: “French Canadian schoolbooks do not encourage respect for the Indians. Some part of the Canadian Catholic mind is not certain of the Church’s victory over the Medicine Man.”

By current yardsticks, though, it doesn’t really matter whether Cohen was being ironic, because we have collectively rejected irony as a means of addressing systemic injustice. In the ’90s, David Foster Wallace criticized irony as “singularly unuseful when it comes to constructing anything to replace the hypocrisies it debunks.” Today, we’ve taken the critique a step further, recognizing irony’s power to uphold the very structures of power it ostensibly denounces. This is particularly true when there is a power difference between the speaker and their subject. Consider the backlash against Kenneth Goldsmith or Vanessa Place, two avant-garde white artists whose purportedly anti-racist work got them accused of, well, racism. Or, closer to home, Hal Niedzviecki’s infamous call for an “appropriation prize” for writers. If such a prize really existed, Beautiful Losers would probably win.

For these reasons, Beautiful Losers will likely continue its slide into the dustbin of history and, with it, our memory of the young author who wrote it, high off his face on amphetamines and sunstroke on the Greek island of Hydra. Instead, we will continue basking in the light of the elder Cohen’s towering icon while listening to saccharine covers of “Hallelujah” on repeat. And this will be a loss, for Beautiful Losers is an important reminder that before Cohen became a saint, he was just a flawed man.