Just like applying for a job at Lumon, cinematographer Jessica Lee Gagné balked at the job of shooting the now-celebrated series Severance, streaming now on Apple TV+.

“I was like, ‘Gosh, I don’t know. An office?’” she tells Inverse.

Gagné’s journey into Severance started when she received an email from actor and director Ben Stiller — the two worked on Showtime’s Escape at Dannemora — in which Stiller raved about the project. But Gagné wasn’t feeling it.

“I was reticent,” she says.

As director of photography for shows like Mrs. America and ads for Gap and Hitachi, she assumed a drama contained to a drab office would be as exciting as filing TPS reports.

“If I’m being selfish, this seems like somewhere where I can’t have fun,” she says. “I adore doing things differently, and I think Ben likes to do that. We were always challenging ourselves to create something new every time we approach something. I didn’t feel like there was space for that [in Severance]. I wasn’t able to grasp the opportunities in it.”

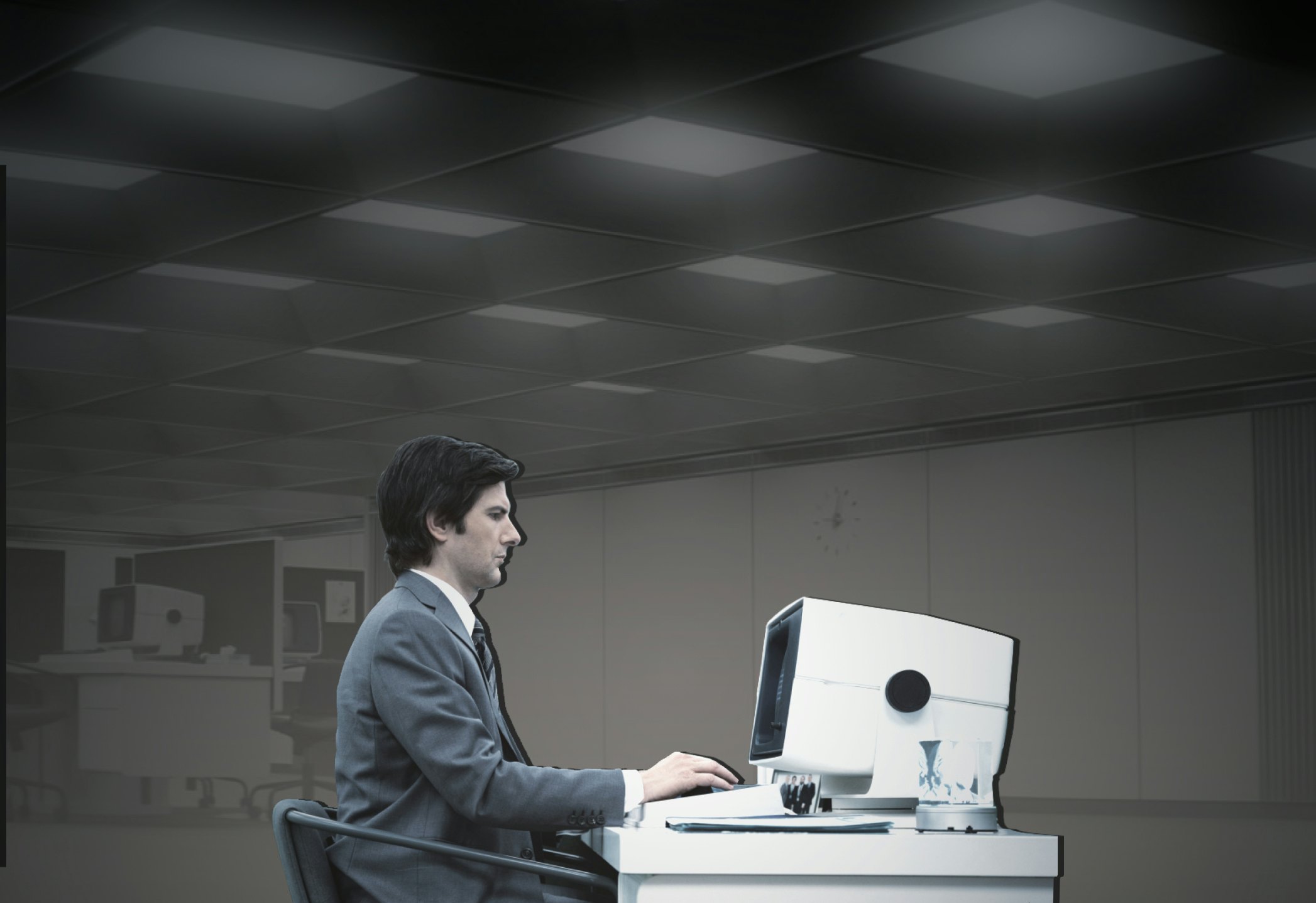

Little did Gagné know what she was in for. Since its premiere in February, Severance has won acclaim as a delightfully eerie sci-fi thriller where half of its narrative takes place inside the spartan offices of the fictitious Lumon Industries. Think Office Space meets 2001: A Space Odyssey, and you’re about there.

Gagné’s work has received special attention online, with Twitter users praising its visuals as “absolutely superb” and like “a painting.”

The work speaks for itself. Watching Severance is like a minimalist fever dream, where clean architectural lines, bold colors, and harsh fluorescent lighting create imagery as beautiful as it is haunting. There’s also the way characters move about their space, with unconventional framing — sometimes too far to the sides or entirely missing from the center — generating uneasy tension.

Partially inspired by the work of photographer Lars Tunbjörk and his 2001 series Office, Gagné sought to tell a story of contrasts informed by the show’s duality of separated egos.

“Severance is based on contrasts,” she says. “It’s an oxymoron. There’s a harmony [in the frames], it feels right, it feels beautiful, but it’s not what you think. It’s trying to be comfortable, but it’s extremely uncomfortable.” This is illustrated rather literally in Severance, as Gagné points out: “This stark world with nothing in it and nowhere to sit, but they have a wellness center.”

In Severance, employees at the secretive Lumon, the worldwide leader in... who knows what, are mentally “severed” from their outside, personal lives. They barely even know their own names. But when employees clock out and return home, they’re left without any memory of their day. The show’s characters refer to their severed egos as “Innie” and “Outie.”

Gagné says she strove to visualize the contrasts between these worlds anchored on identities.

“Ben loves contrast; he's a little obsessed with it,” Gagné says. “Having whites that are white and blacks that are black. He likes pop. That’s what he’ll say, pop.”

“Everything that’s put in front of them is there for a reason to bring something out of them.”

Contrasts are seen primarily in how the inside offices of Lumon are harshly lit — at least the spaces employees are allowed to roam — while the outside world is shrouded in darkness.

“The outside world is a lot darker, more textured, and all these things of reality and real life,” Gagné says, adding that humans affect their spaces as much as spaces affect them. “You become who you are because of your environment a lot.”

But inside Lumon is a septic environment teeming with nothingness. It’s a “purified, empty” place of constant surveillance, as though the people in it are subjects of an experiment.

“It’s like they’re children born into this space. Everything that’s put in front of them is there for a reason to bring something out of them.”

While the décor of Lumon is bare, the few objects the characters use elevate in importance.

Typically, cinematographers like Gagné relish packing frames with information. “You want a lot of things in them.” Textures, foregrounds, and backgrounds full of shapes are what all visual artists seek, but Severance is a different beast.

“Working in a set that had almost nothing in it, we had to ‘reverse engineer’ what was interesting, using negative space to give importance to specific things,” she says. “Every prop is there for a reason; every thing is designed in a specific way. By having so much nothingness, everything becomes very important.”

Gagné says this element to Severance demonstrates how Lumon exerts control. “When you have a frame, and all you see is a computer, a pen, or a Post-It, that gave way to what Lumon is about. This control test they’re doing on people. There’s a reason for everything.”

There is some darkness in Lumon, too. Many hallways, including the ones connecting to the room with the goats, are left dark, which Gagné says foreshadows the secrets that lie at the heart of the company.

“We’re seeing them kind of reach these edges, where characters stop in front of pitch-black nothingness,” Gagné describes. “You don’t know what’s behind there. That’s telling the audience there’s a lot more, there’s a secret there. It’s funny because [the characters] don’t even really acknowledge it. They don’t know. That’s how naïve they are. But the audience knows.”

The contrasts between the worlds of Severance symbolize the show’s ideas about human consciousness. The offices Lumon are vast spaces because the people working in them haven’t any memories. “The inside world is empty; there’s space to create,” Gagné says. “It’s like they’re creating new memories.”

Gagné’s work as a cinematographer isn’t solely composing images for the camera but moving the camera too. In Severance, handheld movement symbolizes the immediacy and spontaneity of life. However, inside Lumon, images turn static and still. Smooth movements like pans and tracking shots intentionally mimic the inhumanity of surveillance cameras.

“This perfect world is starting to fall apart.”

“The approach [for us] was to do a traditional, maybe even more human style [of filmmaking] on the outside and a robotic, mechanical, surveillance aesthetic inside,” says Gagné. “Inside, we wanted to take the humanity out of it. Like this observing machine that’s not necessarily controlled by humans. That’s why it feels robotic.”

Handheld movement eventually makes its way inside Lumon as the characters begin to plot their daring escape. According to Gagné, producer and series co-director Ben Stiller sought handheld movement to indicate their outside humanity seeping into their office.

“It’s seeping in,” she says. “This perfect world is starting to fall apart.” By the series finale, “you’re following them subjectively in a very connected way.”

In the beginning, Gagné questioned what shooting Severance might be like. She doesn’t take all the credit for how Severance looks — “It’s a beautiful example of teamwork” — but it was a growing experience under challenging conditions. Production of the series began in late 2020. “What was very interesting for everyone in the industry was refiguring out work-life balance. We were all coming back from not working for a really long time,” she says. “It got me to understand a lot of things about working with people.”

When there’s so little onscreen in Severance, everything in it matters. Even the goats.

Severance is streaming now on Apple TV+.