During a speech given on International Woman’s Day, French President Emmanuel Macron announced the decision to put forward a bill enshrining abortion rights in the country's constitution. Despite being lauded by women’s rights groups, changing the constitution may be more difficult than it appears.

Perhaps in an attempt to divert attention from the backlash his government is facing over the recent pension reform proposal, Emmanuel Macron on Wednesday, March 8 announced his intention to cement abortion rights in the French constitution as he paid tribute to feminist activist Gisèle Halimi, who greatly influenced the passing in 1975 of the Veil Act granting women the right to abortion and contraception.

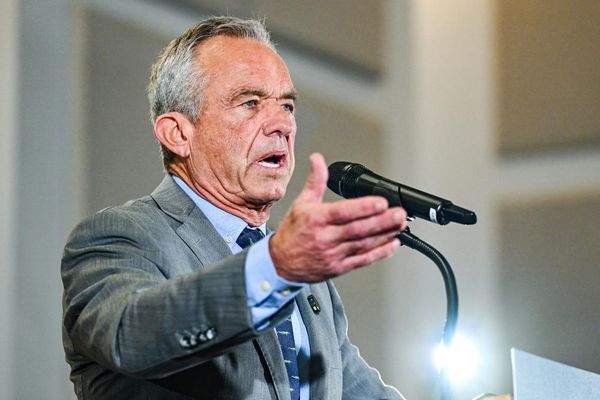

“Progress made through parliamentary talks initiated by the National Assembly and informed by the Senate would allow, I hope, to inscribe this freedom in our founding text through a bill amending our constitution introduced in the coming months,” Macron said at the Palais de Justice courthouse in Paris.

The two parliamentary chambers both recently voted – the National Assembly in November, the Senate in February – on adding abortion rights to the constitution, though in different terms.

While the news was warmly welcomed by women’s rights groups, which saw the move as a “victory”, consecrating the right to abortion in the Constitution is still far from reality.

On one hand, a bill put forward by the government is voted on by parliament in a joint session and passes with a three-fifths majority, contrary to a bill submitted by legislators, which is voted on via referendum and seen as more risky.

On the other hand, contrary to the legislators’ proposal, Macron’s government is opting for a bill that looks to bring about wider change in current institutions instead of one that is specifically targeted at consecrating abortion rights.

The draft law is expected to include changes such as the redrawing of current regional borders and the redefining of elected officials’ mandates, according to people close to the president.

Macron has himself evoked the possibility of returning to a seven-year presidential mandate with mid-term elections to uncouple presidential and legislative elections, according to an interview with Le Point magazine given in April 2022.

Conditions for amending the constitution have “never been less favorable since 1962”

But burying abortion rights in a myriad of other institutional reforms is largely criticised by the opposition, which cites fears of being coerced.

“Emmanuel Macron is starting to take some steps and it’s a good thing. But it’s doomed to fail if he wants to make us agree to things that are inacceptable, such as the return of the seven-year term and the proportionality feature,” left-wing political party La France Insoumise (France Unbowed) head legislator Mathilde Panot said, adding that the failure of the project would then be entirely the president’s fault.

Indeed, with a fractured National Assembly and no absolute majority, it appears quite implausible for Emmanuel Macron to obtain the 60% of parliamentary votes needed to amend the constitution.

“It seems completely unrealistic,” said Benjamin Morel, a public law professor at the University of Paris-Panthéon-Assas. “The conditions for amending the constitution have never been less favourable since 1962. The Senate and the National Assembly currently exhibit different political colours, and the presidential party doesn’t even have an absolute majority in the Assembly. When Nicolas Sarkozy amended the constitution in a significant way in 2008, despite having a relatively large majority in the Senate and Assembly on his side, the bill passed by a single vote.”

Emmanuel Macron already had a taste of defeat during his first term as president when he submitted a constitutional amendment bill in 2018. This bill included the "dose of proportionality" feature regarding legislative elections, in which the parties would potentially be awarded a number of legislators in line with their results at the national level in addition to the legislators elected in each district, as well as a 30% reduction in legislators, a limit on accumulated mandates, and the abolishment of the Republic's Court of Justice. The Benalla affair that came to light in the summer of 2018 put a stop to the reform. It was reintroduced in 2019 before being buried once and for all by the Covid-19 crisis.

Has Macron learned his lesson? At a meeting in early February with his presidential predecessors François Hollande and Nicolas Sarkozy, he evoked the subject of amending the constitution. According to our information, he aims to create a cross-party commission on the subject of reform, which had already been mentioned during the last presidential campaign. This commission would aim at “reaching a consensus along the lines of what currently exists on abortion rights”, the Élysée Palace indicated.

“Freedom” instead of “right”

Macron’s strategy, however, is unlikely to convince the opposition, especially given that the political left doesn’t present a united front on abortion.

The Senate, with its right-wing majority, has voted in favour of enshrining "women's freedom" to access abortion in the constitution. This wording leaves out the idea that it is a “right” to access abortion, which the political left in the National Assembly prefers. It is thus the Senate’s wording that Macron adopted in his speech on Wednesday.

This clash over semantics is anything but trivial. While Emmanual Macron seeks to appease Senators from the conservative party Les Républicains, the use of the word “freedom” instead of “right” has legal consequences, according to Mathilde Panot.

“It’s a pity and dangerous that Emmanuel Macron is choosing the Senate’s version,” she said. “The National Assembly had a strong desire to reaffirm that abortion is a fundamental right for women. By using the word 'freedom', they weaken the text,” she added.

Benjamin Morel, however, does not share this view, and considers that access to abortion is guaranteed by either of the wordings. “The difference between ‘right’ and ‘freedom’ is the fact that the Senate’s version leaves the various methods of access to abortion for the Parliament to decide, while the ‘right’ to access abortion as written in the National Assembly’s proposal would hand this power to the Constitutional Council”, he explained.

Still, the whole debate could very well be a show in political manoeuvring, taking into account the unlikelihood that the constitution will actually be amended. When asked for more information, the Élysée Palace had little to say on the exact content of the future constitutional amendment bill, as well as on the timing and the way in which the cross-party commission on the subject would be organised.

This article is a translation of the original in French.