Whether or not we know it at the time, horror stories have always reflected our societal anxieties. When critics look back to the very earliest horrors, we see King Kong as a metaphor for the Great Depression and the perceived threat of black men to white society. Marking the dawn of science fiction, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein can be read as an expression of people’s enlightenment-era fears surrounding scientists playing God. This rule holds just as true in 2020 – and in the same vein, Host, the new British-made laptop-horror movie that’s leaving audiences shaking, is a film about our anxieties around coronavirus.

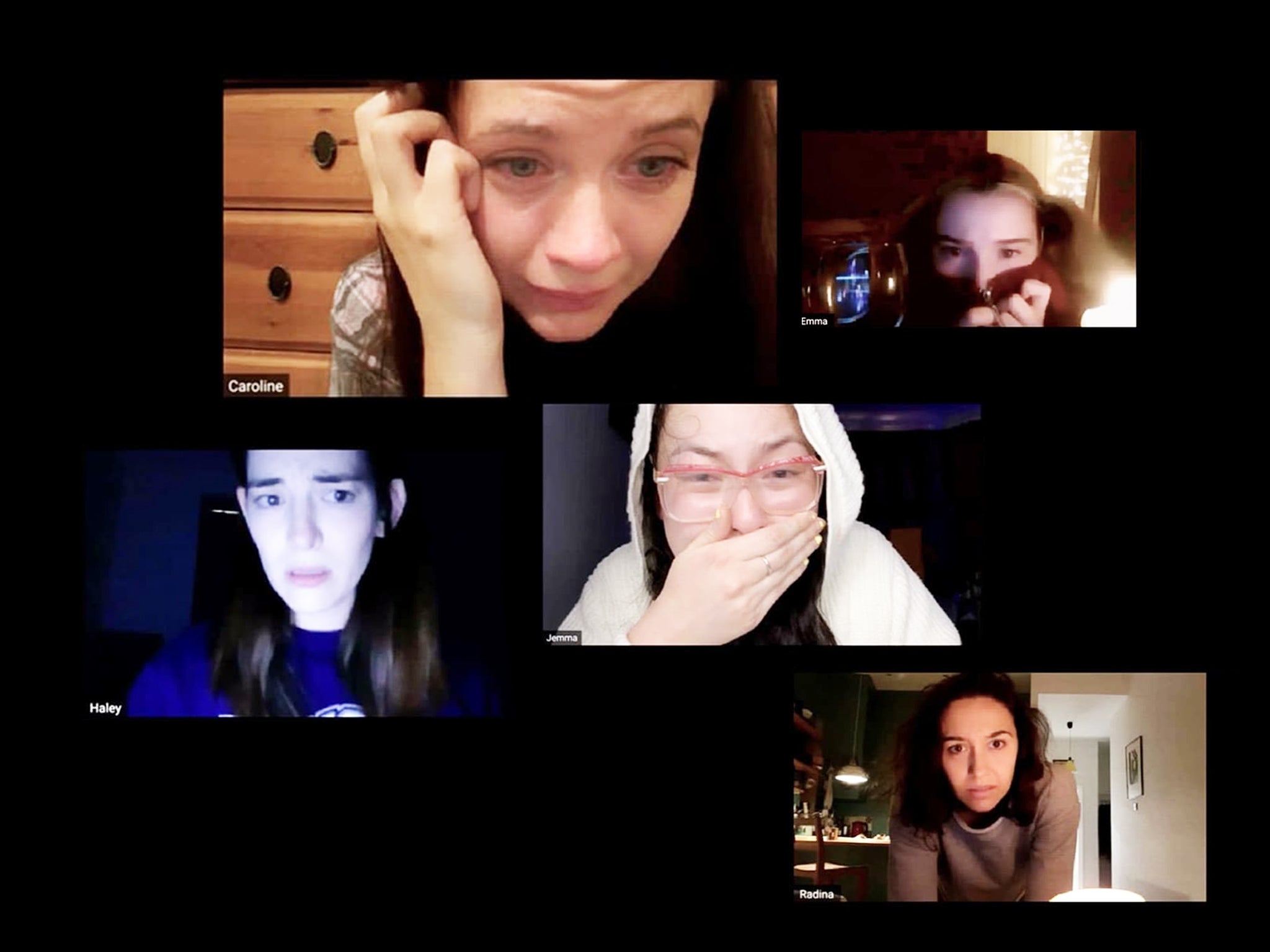

The premise, from writers Rob Savage, Jed Shepherd and Gemma Hurley, may seem a little unassuming, as six friends are roped into a seance and may not live to tell the tale. Our protagonists, monsters and surroundings are horror archetypes at this point – youngish attractive white characters; anonymous demonic spirits that want to torment and kill them; and big empty house(s). So far, so Paranormal Activity. But for Host, there’s a twist: the entire film was made during lockdown and is set on the ubiquitous video-conferencing service, Zoom. So, we watch the rag-tag group as they are petrified and tortured in the individual little Brady Bunch-boxes that are now synonymous with modern-day communication.

Clocking in at just under an hour, the film destroyed me. I’m someone who likes to brag about being unfazed by horror, but I spent most of the film literally hiding behind a sofa cushion, popping my head up to screech every other minute. But beyond the jumpscares (and I cannot stress how many there are) and the gimmick of it being a lockdown movie, the film is genuinely smart and makes a valuable contribution to the genre’s tradition of social commentary.

I see Host as a pandemic tale: the demons that plague the film’s protagonists are airborne and undetectable to the naked eye, much like coronavirus. Characters try all sorts of techniques to track them, like throwing flour down to see their footprints, but the fact remains that if they take one misstep, they might die. Meanwhile, the friends find themselves weaker because they are divided – all socially distancing in their respective homes.

But the most bone-chilling device throughout the film is that sometimes, in the height of the drama, a character will suddenly lose their internet connection and disappear from the screen. That’s scary not only because millennials hate bad wifi but because, in lockdown, we are reliant on the internet to know our friends and family are safe. And so, while the surface-level story of Host is simply a seance gone wrong, the film is really about the terror of being attacked by an invisible force that could be anywhere, and the vulnerability of being isolated from each other.

The video-chat format only adds to the film’s brilliance. There is a unique relationship between technical constraints and horror: sometimes, limitations force creators to think outside the box, which actually makes their movies far spookier. The most famous example of this is when The Blair Witch Projectchanged the landscape for DIY filmmakers in 1999. Shot by three students on handheld video cameras over a long weekend, the film cost a mere $35,000 (in the film budget world, that’s pennies). It went on to gross a hefty $248.6m at the box office, smashing the record for an indie film at the time.

The Blair Witch Project, to put it bluntly, is aesthetically rubbish – the shaky-cam effect meant that moviegoers notoriously experienced motion sickness and some even threw up in cinema lobbies. But it was also terrifying, because the threat to our protagonists almost always lies just out of shot. When you do catch it, it’s liminal – a split-second glimpse or a blurry outline obscured by a night vision lens. What’s more, the fact that it looked rubbish actually made the found-footage film believable. The creators managed to popularise the idea that the film was actually a real documentary, but even critics who knew the truth praised the inventiveness of Blair Witch’s immersive set-up.

Host teaches us the same thing. The Zoom setting is genuinely unsettling because it’s how we spend so much of our time now. Five minutes in, it feels like you’re genuinely on a call with your friends, particularly if you watch it on a laptop. Of course, it isn’t the first film set on a computer screen – director Timur Bekmambetov popularised what he dubbed “Screen Life” filmmaking with horrors like Unfriended, which tells the story of a girl’s death through social media posts and video calls. When Unfriended was released in 2015, it received modest reviews and critics pondered whether the gimmick might have mileage, but in hindsight, the computer-screen format truly captured what communication looked like in the 2010s. By taking to Zoom, and playing with the idiosyncrasies of the platform to make a wider point about the pandemic, Host pushes the envelope that bit further, delivering a timely scare via a medium that feels just as ambitious five years on.

When lockdowns were announced across the world, the bustling film industry, which hinges on a frenetic and tactile production process, ground to a halt. With scores of movies cancelled and postponed this year, and cinemas shutting for months, both creators and audiences are braced for an oncoming industry crisis. But there are glimmers of blue light in the darkness. It’s not surprising that, like The Blair Witch Project, Host was hatched from the minds of young creatives: from 20-part Twitter threads to the new meme formats ushered in by TikTok, young people are constantly utilising technology to tell stories in novel ways. Now, as we grapple with the limitations put in place by the pandemic, it seems that we might have to just get that bit more innovative.

And those innovations could save film as we know it. As the pandemic was declared, the filmmakers and scholars behind the Future of Film report argued that “virtual techniques” are key to making the industry more democratic and accessible, and they also happen to be largely Covid-friendly. CGI, “creative distancing” and Screen Life films such as Host are the kinds of solutions that could get the industry through a pandemic. In theory, that might all sound a little stifling or bleak. But after watching Host, I’m filled with genuine optimism that filmmakers can still create great art in the most tumultuous of times.

Host was produced by Shadowhouse Films and is available to watch via Shudder on Amazon Prime Video