It’s a real underdog story. A bloke from Burnley, who’s made millions selling minibuses, discovers that the big banks are no longer willing to lend money to his friends, neighbours and customers following the financial crisis. So he decides to set up a small bank that will allow him to do just that, offering decent interest, cheap loans and pouring profits back into his community. After going up against City fat cats, he pulls it off. Now, about a decade after the rest of the UK met Dave Fishwick in a Channel 4 documentary about his efforts to launch his bank, the Lancastrian minibus magnate is reigning supreme over the Netflix charts.

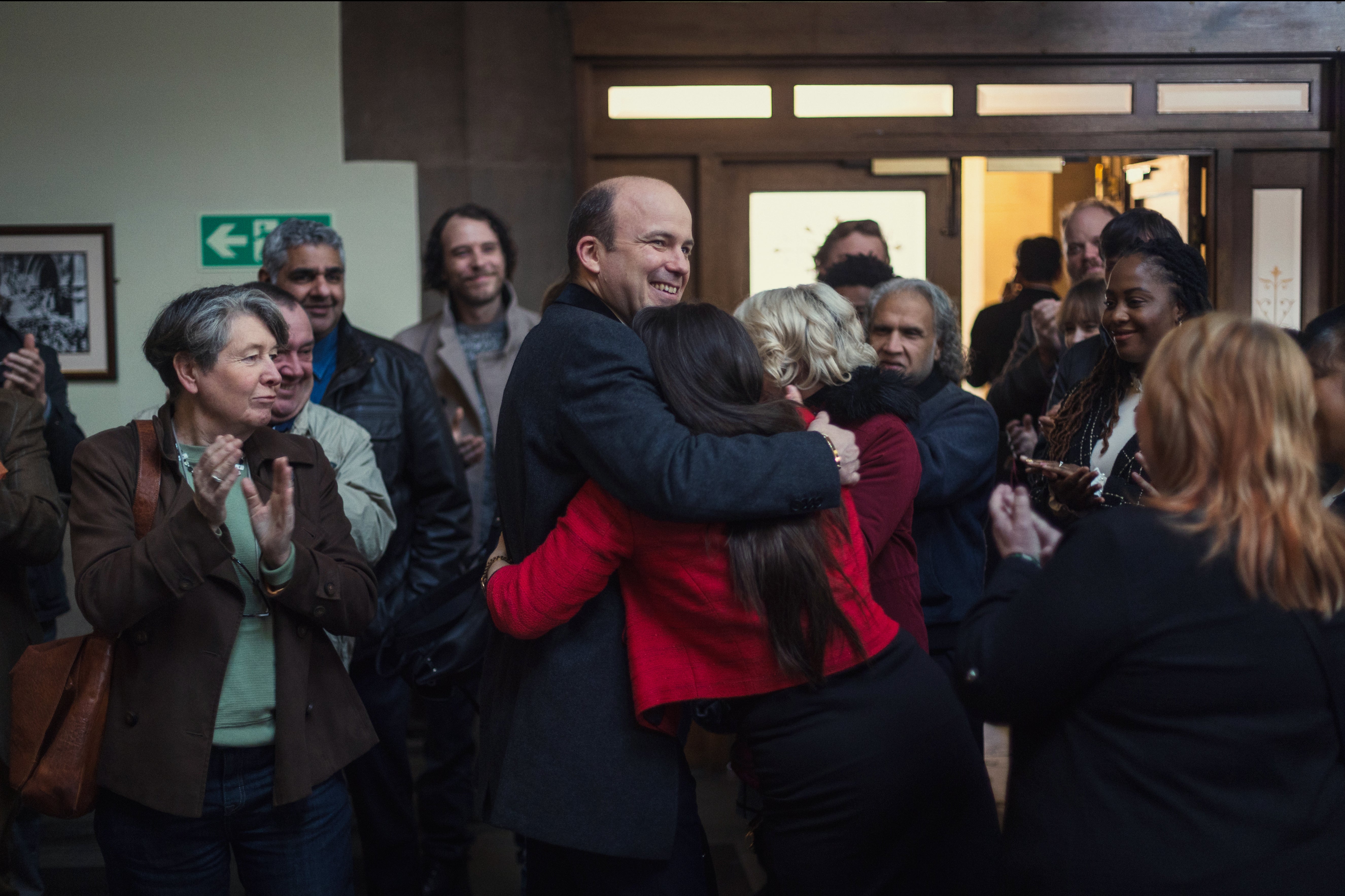

In 2023, the streamer released Bank of Dave, a movie based on Fishwick’s story with Rory Kinnear in the lead role, which immediately topped its UK most-viewed charts. That year, it cropped up in Google’s annual list of the most-searched films, alongside blockbusters like Oppenheimer and Barbie. Last week, a “true-ish” sequel in which Fishwick battles against payday lenders arrived on Netflix; its title, inevitably, is Bank of Dave 2: The Loan Ranger. It’s already reached the top spot.

When I opened my Netflix app last night, a huge, grinning image of Kinnear was staring back at me. Banking on Dave has clearly paid off for the streamer. Just as the real Dave vanquished his detractors at the big banks and emerged victorious, so this relatively unassuming Britcom has punched well above its weight to become a staggering success. So how has the tale of a straight-talking northern entrepreneur managed to grab our collective attention over showier, bigger budget fare?

The films themselves are what I’d call classic three-star movies, in the most complimentary sense possible. They’re solidly made, with a great, multi-generational ensemble cast of British actors, and the scripts are funny but aren’t exactly drowning in subtlety (these are tales where sad back stories are delivered while a cast member mournfully croons REM’s “Everybody Hurts” into a karaoke machine). Essentially, they’re the sort of likeable, not-too-taxing films that are often a much more appealing prospect than the arthouse awards favourite you’d vowed to watch this weekend (especially in the depths of January). Think of them as the cinematic equivalent of a big bowl of pasta.

Both films follow a solid formula. Dave spots an injustice and decides to do something about it. Then, an outsider travels to Lancashire from a busy metropolis. In the first movie, said interloper is a solicitor played by Joel Fry, who’s been hired by Dave to sort out the legalities of his big bank launch. In the second, This Is Us star Chrissy Metz is a New York financial journalist who improbably accepts Dave’s offer of a no-expenses-spared transatlantic jaunt to Burnley. She’s then tasked with interviewing Brits who’ve had their lives turned upside down by unscrupulous lenders.

They may be sceptical at first, but it’s never long before these outsiders are filled with zeal for Dave’s crusade (the turning point usually happens during a karaoke sesh at the local pub). Soon, they’re falling in love with one of Dave’s trusty sidekicks and putting their name down for a season ticket at Turf Moor. Good guys and baddies are clearly delineated for the viewers. Dave and his hardworking chums are affable and easy to root for.

The villains are either posh London City slickers who don’t care about common folk (such as Hugh Bonneville’s Sir Charles Denbigh, essentially a Noughties version of Downton’s Lord Grantham but with no sense of social responsibility) or pantomime figures like Rob Delaney’s Carlo Mancini, who pulls the strings of fictional payday loan company Quick Dough from a mega-mansion on America’s east coast. His New Jersey location and his Italian surname mean it’s only a matter of time before some links to organised crime are dug up, as if he’s a cut-price Tony Soprano.

Moral ambiguity doesn’t really exist here, and the main points are hammered out in exposition-heavy dialogue: “You’re an ordinary bloke standing up against corruption, standing up for ordinary people!” says Dave’s similarly no-nonsense wife Nicky (Jo Hartley) during the sequel. In fact, if you were to take a sip of booze every time Dave refers to himself as “just a bloke from Burnley”, or some variation on that theme, you’d probably end up drunk enough to join him in a rousing rendition of Def Leppard’s “Pour Some Sugar On Me”. Dave is a big fan of a pub singsong, and of the Eighties rockers, who make cameo appearances in both films. Kinnear gives it his all in these karaoke scenes, and in the movie as a whole: his take on Dave is wise-cracking but full of heart, and his Burnley accent is pretty impressive (his father, actor Roy, hailed from Wigan, an hour’s drive down the motorway). This endearing performance is the glue that holds everything together.

Bank of Dave and its sequel are also part of a long and popular tradition in British film: the tale of a group of loveable eccentrics banding together to do something a bit offbeat and stick it to the powers that be in the process. It’s part of the same family tree as movies such as The Full Monty, Calendar Girls and Pride, even if it might lack some of their finesse.

If those are Britcom masterpieces, Bank of Dave is probably the paint-by-numbers version, but it scratches a similar itch. It’s worth noting, too, that while those mid-budget, feel-good films used to be a staple of the British entertainment industry, these days they’re comparatively rare. Producers are finding it increasingly difficult to finance mid-scale projects with recognisable stars but more niche appeal (as opposed to, say, something big and flashy based on pre-existing, bankable IP, or a very cheap indie movie).

Clearly, there’s still an appetite for these kinds of stories. And with so many glaring injustices affecting people today, there are plenty of routes for potential sequels to take. Perhaps we might soon see Kinnear’s Dave calling out the energy companies paying shareholders dividends while their customers struggle to pay their utility bills, or taking on the teams of scammers trying to defraud pensioners over the phone. It seems this Dave-and-Goliath story could run and run.