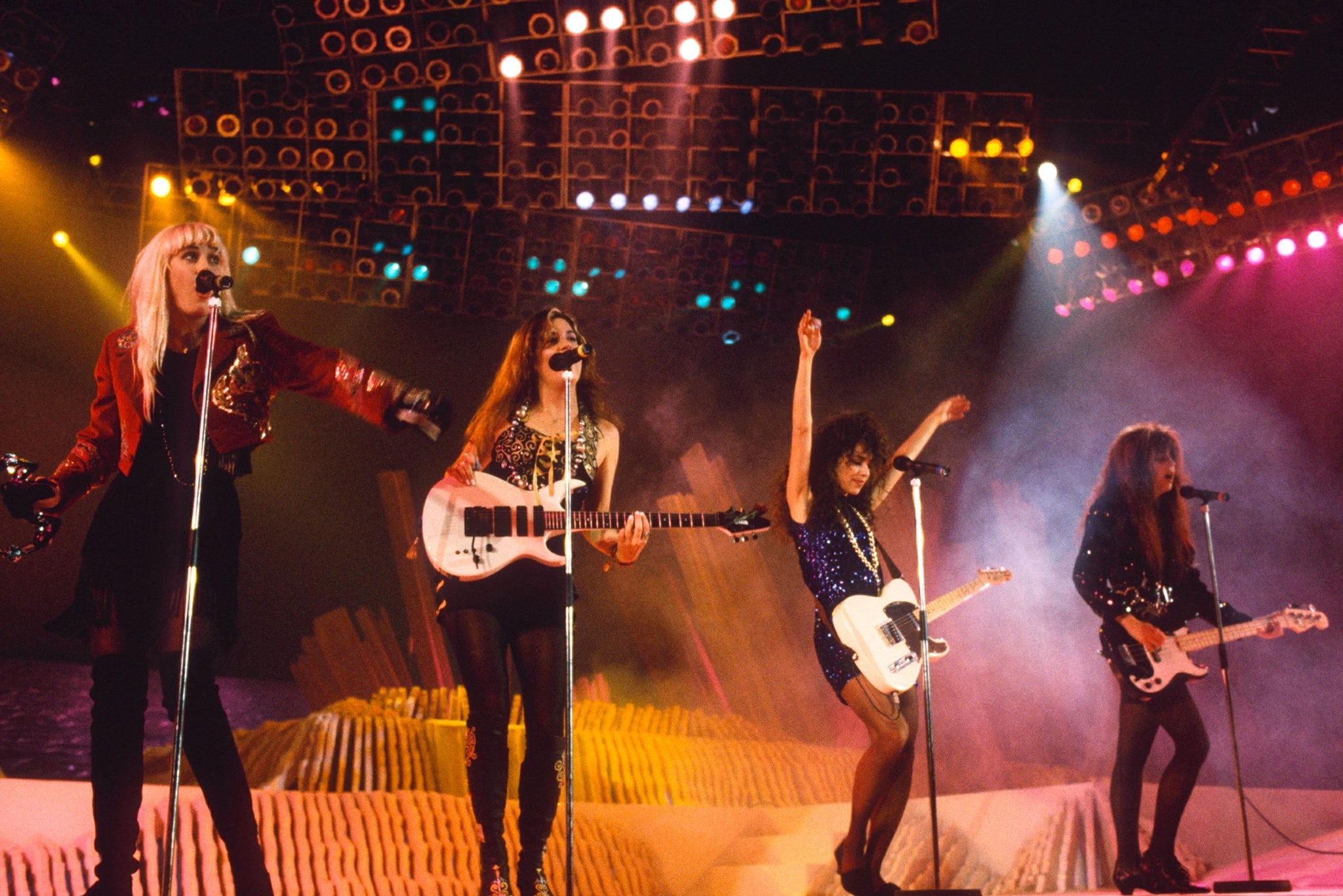

In the autumn of 1989, and just six months after their irrepressibly pretty “Eternal Flame” had hit the top of the charts the world over, The Bangles imploded. It had been an intense run. Three years earlier, they’d reached No 1 with the novelty smash “Walk Like an Egyptian”. A year before that, Prince had jammed with the jangle-pop unknowns on stage in an LA nightclub and offered them a song he thought they might like – “Manic Monday”.

Why The Bangles broke up has been subject to debate. Was it the result of an ambitious member with her eye on solo stardom? Or was their management a set of nefarious businessmen who’d divided, conquered and destroyed one of the most significant bands in modern American history? That might have been it. Or maybe The Bangles began fraying much earlier, the inevitable finale for a group whose most famous tracks were sonically at odds with their initial punk-rock leanings. Perhaps, even, it was all to do with their name. Because of a potential lawsuit from a pre-existing band, The Bangs – loud, made-you-look, not rigidly gendered – became the softer, more overtly feminine The Bangles. The writing may have been on the wall from there.

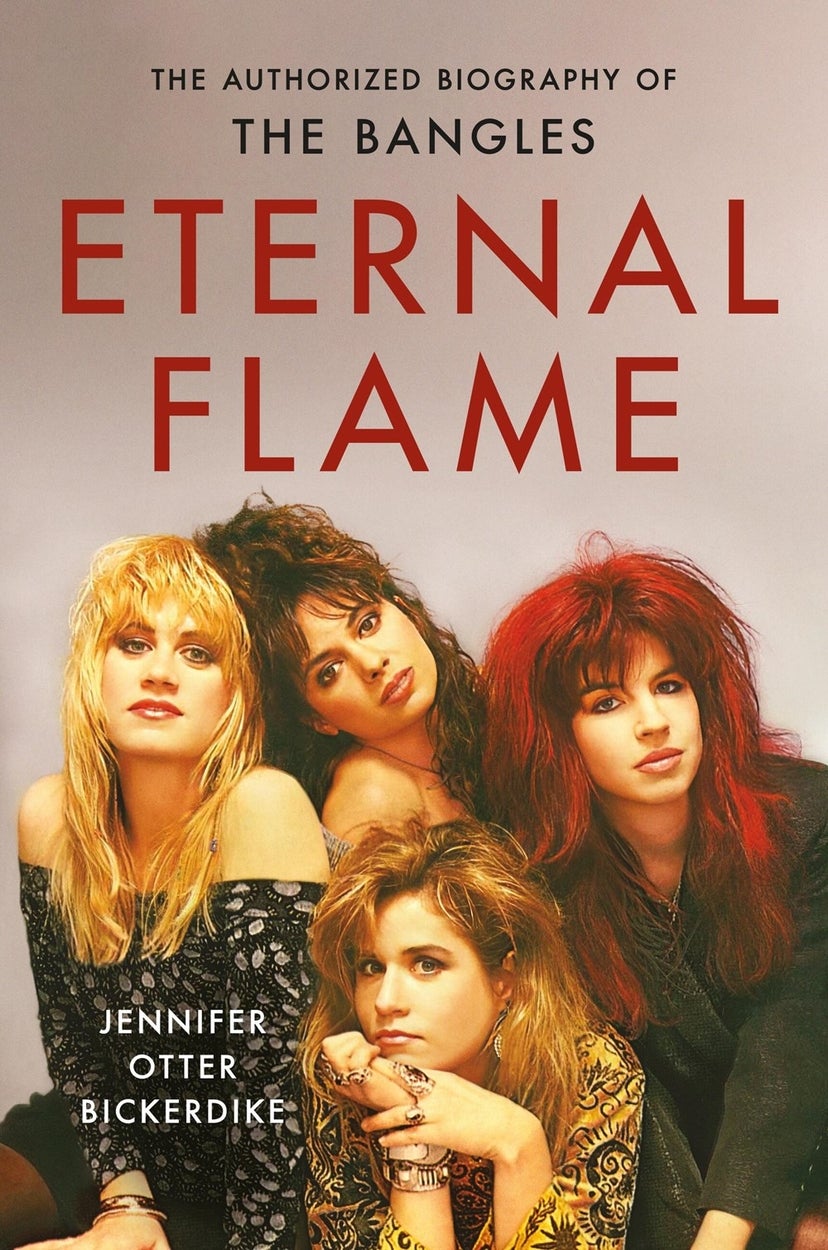

Eternal Flame, a new biography cum oral history of the group by the music journalist and cultural historian Jennifer Otter Bickerdike, does not provide an easy answer to the demise of The Bangles – but therein lies its unexpected thrill. The same incidents are recalled in different ways. Three members of the band’s lineup – Susanna Hoffs and sisters Vicki and Debbi Peterson, who all shared vocals while playing different instruments – contribute separately, celebrating their incredible highs and often disagreeing on their most destructive lows. Producers, songwriters and friends including Boy George and Terence Trent D’Arby supply their two cents.

“There are multiple unreliable narrators in the book,” explains Hoffs today from her home in Los Angeles. (She was that aforementioned member with eyes on solo stardom… or not.) “Even within the band, everyone has their own point of view. Vicki and Debbi had one way they saw things. I had mine. [Bassist] Michael Steele had hers. I suppose that’s what makes it interesting.”

For Bickerdike, an early Bangles superfan, her book felt essential. “The group showed me that you could be totally gorgeous, smart, talented and in control,” she remembers. “And I asked myself, ‘why is there no book on this band that meant so much to me and to other women?’” She corrects herself. “And not just to other women – The Bangles showed men what women could be.”

But the story of The Bangles – as told by its key members – was a lot messier than she had anticipated, serving as a microcosm not just of how the music industry chews up and spits out its talent, but also of the heated interpersonal dynamics of pop groups that attain unimaginable success, then splinter.

Yes, there would be squabbles. There would be jealousies. But that’s what you would expect in any family

“This was the Eighties, and everything was changing,” Vicki recalls. “As a band, we were [representing] complete and utter freedom, liberation and power.” She chews it over. “And yet… did we really have those things? There were things we thought were happening, and then this subtext underneath being decided behind closed doors, and mostly by men in suits.”

The early days, at least, were blissful. The Petersons grew up in California’s San Fernando Valley, raised on a diet of The Beatles, The Mamas & the Papas and The Beach Boys, bands that fused rock and roll with sunny, melodious harmonies. They were determined to start up a band themselves, later recruiting LA native – and fellow Beatles fan – Hoffs via an ad in The Recycler, a Los Angeles newspaper that played a part in forming all sorts of bands from Guns N’ Roses and Metallica to Hole. Steele, who’d played with Joan Jett in The Runaways, would join later. The music the quartet produced was jangly, earnest and lightly psychedelic, with a scrappy, lived-in feel. Think the foot-tapping groove of “Hero Takes a Fall”, or their winsome cover of Katrina and the Waves’ “Going Down to Liverpool”. “There was a lot of punk in us,” Hoffs recalls. “Even though we were kind of power-pop, we were never polished or thought-out.”

“It was raw and so exciting,” adds Debbi, over Zoom from her home in Washington state. “We were playing these sweaty, disgusting clubs and having a fabulous time, and everybody was going in a similar direction. But then all the other voices came in and kind of tore that apart.”

Even today, spread across continents and time zones (I connect with Vicki in London, where she’s on holiday), the women occupy clear roles in the Bangles’ ecosystem: Vicki feels like the leader, bracingly honest while also a natural peacekeeper; Hoffs is the most emotional, tearing up at one point, and full of positive enthusiasm and enjoyable digressions; Debbi is the most open, both about the harsh realities of being in the group, and how much she was personally affected by its drama. All wax nostalgic on the early years of The Bangles, and their DIY approach to gigging, promoting and dressing. And they’re quick to pinpoint the arrival of major-label attention as the moment things went awry.

“These were young women,” Bickerdike says. “It was a s***load of work, and they’re in their early twenties and on the road having to make all these decisions with no one looking out for them. Because the label’s looking out for the product.”

The band’s debut All Over the Place was released in 1984 to moderate success, but a tour with Cyndi Lauper raised their profile exponentially. Sensing an opportunity, Columbia Records took a vested interest in the group’s second album. “The pressure changed, and budgets changed and attitudes changed,” Vicki sighs. Recording of 1986’s Different Light was therefore a tortured affair, with producer David Kahne insisting upon a pop polish, one that came into sharper focus after Prince – having become besotted by Hoffs in music videos – presented the group with “Manic Monday”. That track gave the band their first mega-hit, alongside enormous amounts of free publicity courtesy of Prince and Hoffs, who were never an item – and barely even met – yet became a media fixation. (“Who’s the one that slept with Prince?” Joan Rivers once asked the band during an interview.)

The general focus on Hoffs became an issue. Songs featuring her lead vocals repeatedly became singles; music videos and TV performances seemed to zero in on her face. Some of the book’s participants insist that Hoffs was a natural pop star, able to better work the camera than the rest of the band. (This, inevitably, gets disputed too.) Hoffs herself, though, insists that she was blameless in her increased visibility, and would always correct journalists and label execs who framed her as The Bangles’ frontwoman. She says, too, that a famous shot in the “Walk Like an Egyptian” video – in which her wide eyes glide from side to side – was a fluke.

“The camera was very far away – I could hardly see the camerawoman as she was using a long lens and just zoomed in for that moment. It was what it was. It wasn’t intentional.” She admits to being hurt by the way she is characterised in some of the book. “It was upsetting to read words being put in my mouth, and painting me as somebody ambitious in a way that the rest of the band wasn’t. Because we were all ambitious to have success. Yes, there would be squabbles. There would be jealousies. But that’s what you would expect in any family.”

For the Petersons, it literally was family, which added its own difficulties for Debbi. “I didn’t know where I fit in,” she says. She had only just graduated from high school before hitting the road with the band. “I had a very strong older sister, and Susanna was very strong and self-aware. I felt like lukewarm water.” She struggled, too, with the increased focus on the band’s appearance. “This was the start of the video generation, so you had to look amazing at all times,” she sighs. “I remember after we did Top of the Pops or something, Susanna saying, ‘How did we look?’ – because this stuff would get stuck in your head. I remember thinking, ‘shouldn’t we be asking ‘how did we sound?’”

Everything, released in 1988, would prove to be the final Bangles’ album released at their commercial peak, and was the product of each Bangle working with their own producers on their own songs. The label also preferred Hoffs’s more radio-friendly tracks, among them “Eternal Flame” and the rockier, sexier “In Your Room”. This only provoked further discord. Vicki is quick to praise “Eternal Flame” today, but she admits to having problems with it at the time. “I was a freakin’ rebel,” she says. “I was determined to make The Bangles the rock band that we started out as. And I knew that to do something so blatantly pop … there was a resistance [on my part].”

The group toured the Everything album, but friction between all four Bangles became overwhelming. Management dangled potential solo deals in front of Hoffs and Steele, while the band as a whole were overworked, unhappy and non-communicative. “If we were a boyband, we’d have just punched each other out,” Debbi laughs. “But we didn’t want to confront things. I remember once Michael Steele got really mad and threw a chair across the dressing room – so there were episodes, but generally there was nothing. We just didn’t talk. And we should have.”

“Communication is crucial in bands,” adds Vicki. “Unless you’re working as a unit and talking as a unit, the band will fracture and then, of course, plenty of people will start jumping in to divide and conquer. Which is what happened with us, ultimately.”

At management’s behest, a meeting was held in 1989 to discuss the future of the band, where Hoffs and Steele announced that they couldn’t move forward with The Bangles. The Petersons felt blindsided. “It was like the worst break-up you could ever imagine,” Debbi says. It took years for the three factions to speak to one another again. At the insistence of Hoffs’s husband Jay Roach, the filmmaker behind the Austin Powers movies, the group reunited to record a song for the Austin Powers 2 soundtrack in 1999, and later toured and made a reunion album, 2003’s Doll Revolution. More touring followed, before the mercurial Steele departed (she has since retired from public life and declined to contribute to Bickerdike’s book) and the band went their separate ways – potentially forever. “But it was so good to connect again,” Debbi says. “We’d had space to mature.”

Today, the group is sanguine about their history and grateful for their time in the spotlight, even if looking back on some of it was painful. “I have a very deep and abiding love for my bandmates,” Vicki says. “So many times I wanted to kill them all, you know? Yet I just adore them.” All are eager, too, for Bickerdike’s book to serve as a reminder of the band’s significance: along with The Go-Go’s, with whom they were endlessly compared at the time, they served as one of the first and certainly most visible all-female pop-rock bands in American music history.

“The last 10 or 15 years, there’s been a more superficial appreciation for The Bangles,” Vicki says. “The hits still resonate, but not necessarily the band or our story, or how we fit into the giant scheme of things. And if somebody wants to learn what was going on in music in the 1980s, I want The Bangles to be a part of that story – we deserve to be. I don’t know that we’ve ever gotten that kind of respect.”

“I’m so grateful for those years,” Hoff says, her eyes moistening. She still remembers the feeling she had during her first meeting with the Petersons, where the three of them sang Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” together. “I knew in that instant that something huge had just occurred in my life.”

She apologises, mopping at her eyes.

“I had no idea what was to come, and yet it happened,” she says. “It was a magical, miracle thing.”

‘Eternal Flame: The Authorised Biography of The Bangles’ by Jennifer Otter Bickerdike is available now via Hachette

Clara Mann: ‘We’re very alienated from each other – live music is a remedy for that’

Lady Gaga’s 123 songs ranked, from Born This Way to Abracadabra

Lady Gaga lost her edge – her new album needs to bring it back

Glastonbury is finally taking the risk and putting Gen Z artists front and centre

19 hit songs hated by the musicians who wrote them

Boygenius’s Julien Baker and Torres on their queer country album