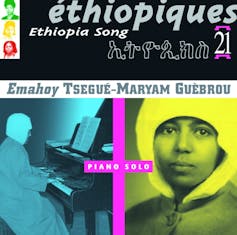

As the Ethiopian pianist Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou approached the age of 100, fans and music critics from the US to Ethiopia, Israel to Europe have been eagerly rediscovering her work. But the Addis Ababa-born pianist, who has died at the age of 99, has been a source of fascination to connoisseurs. Especially after a disc in the iconic Ethiopiques series (issued by Buda Musique) was dedicated to her work in 2006.

The classically trained musician was associated with the jazz genre and spent her life in a convent. She will remain in death as much as in life a figure of beautiful contradictions. Her legacy as a female instrumentalist, a religious composer of secular music and an ascetic who created work of astounding beauty requires of fans to listen for nuance.

A monastery in Jerusalem

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Christian quarter of Jerusalem is as good a place as any to begin to explore that legacy. Enthusiastic fans of Ethiopian music might turn up, having heard a rumour that there is an Ethiopian monastery on the roof. The church has been embroiled for decades in a quarrel over land rights. But in all seasons, Ethiopian monks sleep here in austere pods with close proximity to history and little protection from the elements.

Guèbrou lived this monastic life for decades, having moved to Jerusalem in the 1980s during a difficult period of military dictatorship under Mengistu Haile Mariam and never returning permanently to Ethiopia. She was known to continue to practise the piano in her room in the convent well into her 90s.

While musicians spotlighted in the Ethiopiques series tour Jerusalem periodically, she was the only one to move there. So, among her other legacies, her life story brings the Kebra Negast – the foundational epic literary work of Ethiopian civilisation centred on the transfer of the Ark of the Covenant from Jerusalem to Ethiopia – full circle into the complex geopolitics of the present day.

Who was Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou?

Guèbrou was photographed extensively in the bedroom of her Jerusalem convent, the scene of her remarkable fourth act. How she got there is as unbelievable a story as any of the 20th century.

Guèbrou’s life has been well catalogued in profiles and documentaries, and by a foundation created by her family.

She was born in 1923 to an upper-class family in Addis Ababa, and she was trained in western classical music as a young woman. She is known in particular for her virtuosity on the piano, but her training was wide-ranging, including expertise on the violin.

As Ethiopia underwent a series of dramatic political changes across the 1900s, Guèbrou’s rights as an educated woman shifted, too. With the Italian occupation in the 1930s, she and her family spent time in a prison camp.

Under the rule of Emperor Haile Selassie, she spent time as a working musician alongside the Imperial Bodyguard. With the rise of a military junta that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991, she departed for Jerusalem. She remained there until the end of her life, a religious Christian adopted as a figure of reverence among the music fans of Israel’s 140,000 citizens of Ethiopian lineage.

The power of her music

Guèbrou’s work is usually described as highly syncretic – drawing from a wide variety of musical sources – mostly non-Ethiopian references from the western and jazz canons. Critics point to her long improvisations and her free adoption of the tonal ranges that the piano can accommodate. No doubt, her gender and instrument influence this description. Women in Ethiopia are most often singers and dancers, not instrumentalists. If they do play an instrument, it is the krar, a six-stringed lyre on which they accompany their own singing.

Then there is the sound of her piano playing. Western instruments have been long familiar to Ethiopia; the Arba Lijjotch, an orchestra of 40 Armenian orphans, made an impression on Selassie in 1924. The emperor took a liking to brass bands and was rarely received in public without one. The sound of the brass band merged in the 1960s and 1970s with the sound of the Azmari, a self-accompanied folk-poet, creating the musical style that is so well captured in the Ethiopiques albums.

Each volume is dedicated to a different musician, such as singers Mahmoud Ahmed and Asnaqetch Werqu, and volume 21 is a comprehensive study of Guèbrou’s repertoire. As music critics have noted, her work sounds markedly different from the heavy brass of the 1970s scene in Addis Ababa. But that is sometimes more a question of instrumental timbre than tonality. A careful listen helps to identify close engagement with a variety of Ethiopian musical traditions.

Guèbrou recorded over 100 tracks, but footage of public performances is exceedingly rare. Most fans will know the image of her sitting by her piano in religious garb as she speaks to the journalists who sought her out over the years. Religion, music and good deeds are indistinguishable from one another, as she explains the purpose of the charity founded in her name:

After I asked God for his will, I determined to publish and use the money to fund children and young people for their education.

The track Homesickness has no lyrics, so it can be mistaken for an original composition. But its first measures reveal that it is none other than Tezeta, arguably Ethiopia’s most famous and widely recorded song.

Guèbrou has started it with the same ascending pentatonic motive (a musical scale with five notes per octave) as several of the artists who cover the song on Ethiopiques Volume 10: Ethiopian Blues and Ballads. While this particular version has no lyrics, the homesickness described in the song refers to a lost lover and to a lost time and, for an emigrant, a lost homeland.

The amazing contradictions in Guèbrou’s life layer alternative readings on top of this loss. And they pose to the close listener the possibility that this iconic performer of Tezeta – a woman in exile without romantic entanglements – embodied for Ethiopians an elusive state of total artistic and spiritual unity.

Ilana Webster-Kogen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.