Naomi James came to NZ to head up a loss-making oil refinery. This week she leaves as the CEO of a profitable fuel import terminal operator. She gave her exit interview to Nikki Mandow

When Naomi James announced her company’s annual result at the end of February, a couple of weeks before she headed back to her native Australia, she was speaking as the outgoing boss of a stock market darling.

Channel Infrastructure’s share price had increased 50 percent over the year, in a market down 8 percent. The company was making money for the first time since 2019, and paying a dividend again.

Congratulations, purred the analysts on the conference call.

The success is bittersweet. James arrived in the country three years ago to lead New Zealand’s only oil refining company, Refining NZ.

These days Refining NZ is no more. Instead the company is called Channel Infrastructure, a fuel import storage company and pipeline operator. The refining equipment is being decommissioned; the plant could be sold overseas.

But the company survived. More than 95 percent of staff have a new job or opportunity, James says.

And that was far from a foregone conclusion.

Newsroom did one of the first media interviews with James when she first arrived. Over the previous five years the company had gone from a $151 million net profit after tax to a $4m profit to a $198m loss.

“Can our oil refinery survive?” we asked.

READ MORE: * Can our oil refinery survive? * Grim news for the planet, great news for Channel Infrastructure * Closing our fuel insurance policy

James must have been wondering that too. She’s a lawyer by training but arrived in New Zealand with 20 years of experience working in heavy industrial businesses – steel, iron ore, oil and gas.

She knew the impact of the commodity cycle on these industries – you need to be able to survive the bottom of the cycle, and that often requires major restructuring.

She knew too it didn’t always end well. James was working for the Australian steelmaker Arrium in the 2010s as the heavily indebted company moved towards catastrophic failure. It announced a AUD$1.9 billion loss in 2015 and went into voluntary administration in April 2016, owing more than A$2.8b to creditors.

The external facts were dire. “It was like every driver for our business went the wrong way at the same time – low iron ore prices, incredibly low steel prices and market, and low copper prices.”

And the company didn’t move fast enough. “It ran out of runway,” James says. “It ran out of money and time to trade through that.”

James wasn’t the overall boss at the time, but she was was appointed chief executive of strategy in 2014. She couldn’t save the company.

She says she experienced at Arrium a people-focused approach to leadership, which created loyalty and commitment, but also at times creating a reluctance at the top to make the hard decisions.

“It taught me the importance of time, of not running out of time.”

Her next job, for the oil and gas company Santos, was different.

“I learnt the hard edge of strong performance management and how setting ambitious targets and keeping score of what counts delivered results,” James says. But at times people could be a side-thought.

The Refining NZ role gave James her first opportunity to test and evolve her version of transformational leadership.

“I wanted to test if it was possible to combine people-centred leadership with strong performance management.

“I have a love of complex change situations – the imperatives of those situations force you to really test what is possible, can bring out the very best in people and drive people and organisations to work to their full potential in order to survive."

“I had no idea at this point whether or not we could make the refinery work. Nor did I know with confidence whether we could find a plan that would enable our business to survive.” – Naomi James, Channel Infrastructure

If James thrived on complexity, the 2020 Covid lockdown took it to the next level. Added to a tough global situation – slumping refining margins and smaller, older plants being made uneconomic by bigger regional players – was the short term pain of being the main supplier of petrol, diesel, kerosene, bitumen, and fuel for planes and ships for a country that (mostly) didn’t need any of those things.

New Zealanders weren’t driving, we weren’t flying, we weren’t repairing our roads or making much stuff in our factories. At the same time ships were still arriving with crude oil for processing.

“I had no idea at this point whether or not we could make the refinery work. Nor did I know with confidence whether we could find a plan that would enable our business to survive.”

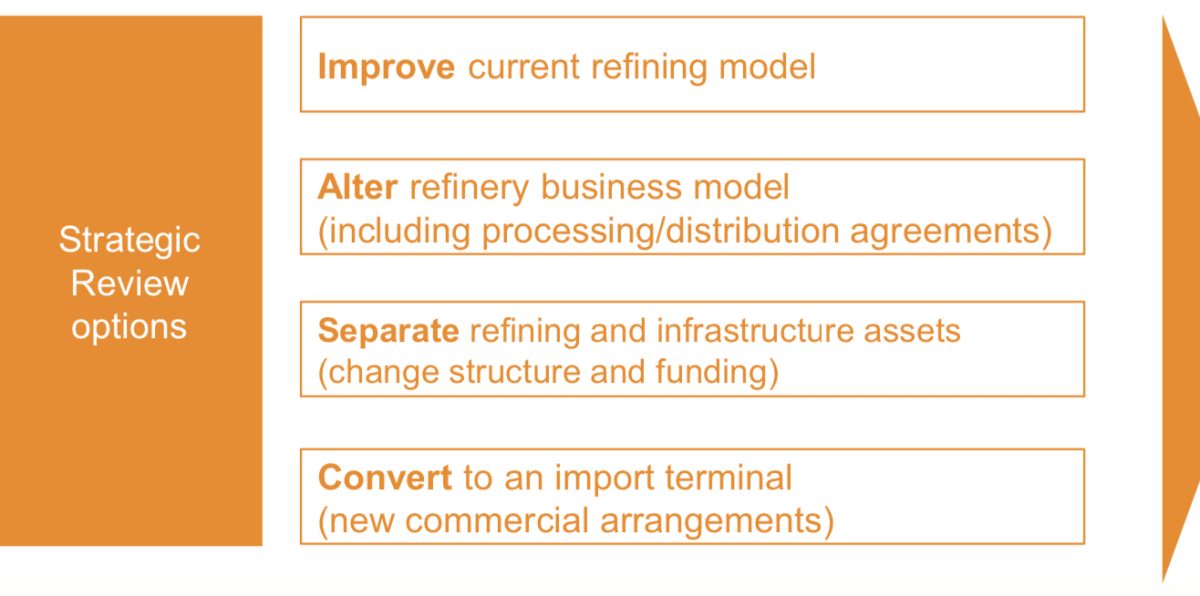

So in her first week in the job, stuck in Adelaide because of the Covid border closures but with lessons from her time at Arrium top of mind, James announced short-term measures to get the company to break-even – including a three-week-on, three-week-off production schedule very few, if any, international refineries had tried before, followed by a six-week Covid-induced shutdown – and a wide-reaching strategic review.

“I knew we couldn’t waste time because of the situation we were in. I knew there was going to be a business which could survive, but I needed to work out what it was and I needed enough runway, enough time to build and execute a plan to get there.”

Three weeks later James managed to get to New Zealand, and for the next fortnight ran Refining NZ out of a quarantine hotel, her three sons down the corridor.

(One of her clearest family memories of that time is how, in the absence of weights to do his workouts, the oldest boy used to carry the youngest when he did his lunges.)

Within a month there were four options on the table, from adjusting the status quo, to closing the refinery.

By the end of the year, Refining NZ was in parallel discussions with its customer shareholders (Z, BP and ExxonMobil) over short-term moves to “simplify” refinery operations to get costs down, and longer term plans to move to a import-only model.

In August 2021, shareholders voted in favour of the import terminal plan and name change, and that went through in April 2022.

If that sounds smooth sailing, it wasn't.

"What we forget is change is about bringing people with us and that’s about hearts and minds, that’s the 'how' of change. The rightness of the decision doesn’t make it any easier to execute. In fact, it’s often the opposite. Doing nothing, maintaining the status quo, is almost always the easier path."

James’ “stakeholder puzzle” – the different hearts and minds on her radar – ranged from Government, which needed to consider the wider implications for NZ’s fuel security, through customers – large global companies with a combined market capitalisation of over $500 billion, compared with Refining NZ’s size of only a few hundred million – through lenders and shareholders, to staff and the local community.

“We needed to plan for and work through what would be a huge transition for our workforce and our local community, making sure we retained the capabilities we would need to safely run, close and decommission a highly hazardous facility and establish and operate as an import terminal, as well as consult with iwi and other local stakeholders on the impacts of our changes.

"The rightness of the decision doesn’t make it any easier to execute. In fact, it’s often the opposite. Doing nothing, maintaining the status quo, is almost always the easier path." – Naomi James

“And through all of this, we needed to continue to operate a major hazardous facility until the day we closed, keep our people safe, keep fuel flowing to New Zealanders, while transforming every aspect of our business.”

James believes it is possible to combine complex transformation and people-centred leadership. The turnaround story, combined with the fact 97 percent of staff either have new jobs or are in training or have gone on to “other opportunities” speaks to that, she says.

Same with the company’s ‘six plus six’ decision – a commitment in early 2021, several months before shareholders agreed the final plan, to give all staff a minimum of six months’ notice plus six months’ redundancy pay.

“This wasn’t just the right thing to do but also made good business sense as it helped us retain our staff. We saw incredibly low staff turnover through our transition,” James says.

Whangārei-based Edward Miller, a researcher and policy analyst for the First Union, which represented workers at the plant in negotiations, disagrees strongly with James’ decision to close the refinery. He argues by the time the plant actually shut, the fundamental financials had shifted and closure was not the best option.

Still, given that caveat, Miller accepts Channel Infrastructure “did more than we expected” to get people placed into jobs.

“In some instances, they went further than most employers, and people ended up with decent work by and large. The process was pretty good.”

Financial controller Kylie Linton joined Refining NZ in 2009 on secondment from KPMG and never left. She says an important part was keeping staff in the loop with what was going on.

“Naomi and the corporate leadership team were really aware of what the uncertainty was doing to people on site. We craved information.

“What resonated from the beginning was there was a timeline and there was always feedback on where on the timeline we were.”

Linton says her own leadership style changed working under James. Coming from an accounting background, “I’ve been all about the numbers,” she says. “Naomi showed me the importance of the human aspects.”

It can be as simple as taking time to chat to staff in the lunchroom, or maintaining an open-door policy.

“I was gutted when she said she was leaving, although I always knew it was going to happen.”

James Miller wasn’t surprised either. Miller was a director of Refining NZ right through the transition and was appointed chair in June last year. His portfolio of directorships includes the NZX, Mercury and Vista; in the past he’s been on the boards of ACC, Auckland Airport and Vector.

“I’ve never seen a chief executive like her – not even close,” he says. “I personally found her amazing to work with. I’d hire her in a flash if I had a high complexity turnaround situation. But I probably wouldn't hire her for a boredom job.”

Another CEO might not have saved the company, he says.

“She’s phenomenal in a situation of major change. She can handle complex law and complex finance. She is both tactical and strategic, but at the same time has a high level of empathy.

“This was a very painful situation for the staff, and for Northland, and she can be really caring, and understand the subtleties of people."

Planning for failure

Miller says James brought an extraordinary attention to detail to her leadership.

“She was phenomenally well prepared in board meetings – she left nothing to chance. ‘How will this play out?’ is a great Naomi line.”

James talks about the importance as a leader of thinking backwards as well as forwards – anticipating potential future roadblocks and working out how to deal with them before they happen.

In a speech to the University of Auckland’s Business School the week before she left, she quotes James Clear, the author of Atomic Habits, about the concept of ‘inversion’ as a critical thinking tool.

“Success is overvalued. Avoiding failure matters more.”

She remembers there were more than 50 board meetings during 2021, as opposed to the usual one a month, as the company developed detailed transition plans to move from refining to being an infrastructure player.

“It was painstaking, but by looking at every element of how we executed our plan – our workforce, our assets, our operations, our commercial arrangements, our balance sheet, and each of our stakeholders – and bringing a strong risk focus across these areas, we identified the things that could go wrong.”

Another of James’ leadership mantras comes from Admiral Jim Stockdale, via 1990s management book Good to Great by Jim Collins.

Stockdale was the highest-ranking US officer captured during the Vietnam war and spent seven years in a prisoner of war camp, including being tortured on multiple occasions.

“What Stockdale discovered was the key to survival,” James says. “Prisoners of war who were full of hope, saying ‘We’ll be home by Christmas’ would die, as the reality of ‘We may not be home for many Christmases' became evident.”

The ones who survived were able to confront the reality of their situation, while maintaining an unwavering belief they would prevail, and that philosophy works for companies in difficult situations, including Refining NZ as it was in 2020 and 2021, James says.

“What drives high performance in organisations is combining a fully realistic view of what it’s going to take, with an overly optimistic belief in your ability to achieve it.”

An Australian in Aotearoa

What else has she found in her three years in the Refining NZ job?

First, surprising as it may seem given the experience of former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern as a female leader, it might have been worse in Australia.

“I never found being a woman an issue in New Zealand. And I would say that is different from Australia, and that’s a really good thing. I’ve worked with men all my career, women too, but mostly men, including incredible leaders who have taught me a lot and a few who taught me who I didn’t want to be as a leader.

“But in New Zealand, less often did I feel there was a reaction of: ‘Oh there’s a woman running the show’, and that’s unusual.

“Perhaps there is a little less ego here in leadership, though that’s not to say it’s absent. But I’m optimistic because I think there’s never been a better time to be a woman.”

Second thought: the Government needs to do more to deliver certainty to businesses around its policies for dealing with climate change.

“If you go back to 2019 and the Zero Carbon Act, we legislated an aspiration, and it’s a good aspiration, but we did not have a plan to meet that aspiration.”

And although Government has made some progressive, particularly with the work of the Climate Change Commission and the carbon budgets, New Zealand still doesn’t have a plan to meet its aspirations, she says.

“We’ve got a plan to make a plan; we’ve said we’re going to build an energy strategy. Terrific. Now we actually need to go and do it.”

Third: the conundrum of innovation and execution. As an Australian with a Kiwi mother, James worries about passing judgment on the NZ psyche – but she has views on New Zealand’s number 8 wire mentality, born of our physical distance from the rest of the world, and a perilous landscape of volcanoes and earthquakes.

“I came to understand that it was in a crisis that people and organisations like ours were at their best. The innovation was incredible. But the question I asked our team was, ‘What if we led and worked like we do in periods of crisis at other times, to avoid the crisis?’

“At the same time, as I drove back and forth from Auckland to Marsden Point each week and saw the same roads still being built after three years, there seemed to be a challenge here in execution ... The question is: Can we build more capability by planning for success and planning for failure to remove the things that get in the way of getting things done?”