Aperitivo culture on the whole, if you will, has had quite a moment recently — both at restaurants and in bookstore aisles. One of the first cookbooks I can recall tapping into the bounty of Italian snacking was Stacy Adimando's "Piatti: Plates and Platters for Sharing, Inspired by Italy," but in the years since, there's been such a huge surge in interest.

Much like everything lately, TikTok has been the thumb on the scale. The amalgamation of pandemic snacking, the second Italy-set season of “White Lotus” and the rise of “girl dinner" have actually catapulted the trend.

To be clear, I’m not upset about it. I am half Italian and was born and bred in Northern New Jersey, so it should go without saying that my food lens is entirely colored by Italian and Italian-American flavors and influences. There has been many a meal during which I just eat my body’s weight in Parmigiano Reggiano, mozzarella and olives. I used to be obsessed with prosciutto and bresaola and the like, but since giving up all non-poultry proteins, I’ve been relegated to the wide, wonderful world of Italian cheeses, breads, condiments and primarily vegetarian treats.

There’s a certain live-and-let-live, laissez faire quality to eating like this. For people cosplaying as a vacationer on the Amalfi Coast, there may be no better gustatory way to approximate the sensation.

At its core, though, aperitivo, Italian happy hour and snacking culture is so much more than a trending topic or how one eats on holiday — it’s a years-old, cherished custom that has been commonplace and the “default” throughout Italy for generations.

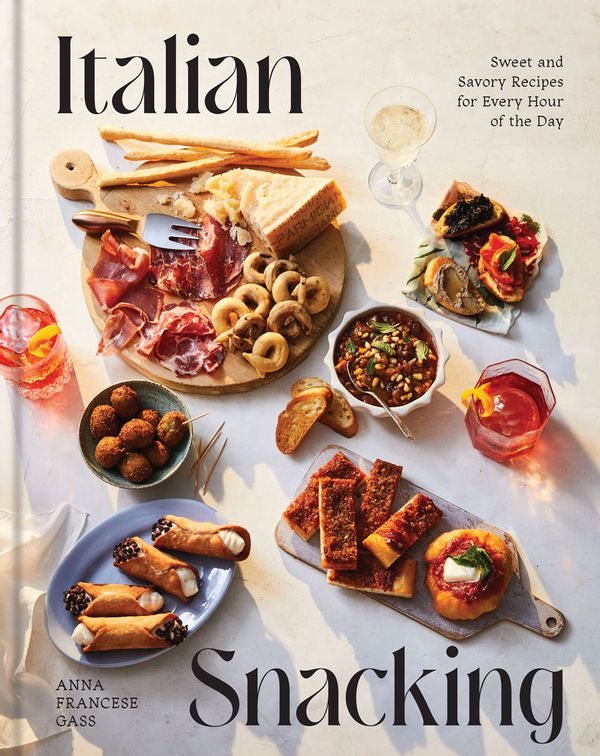

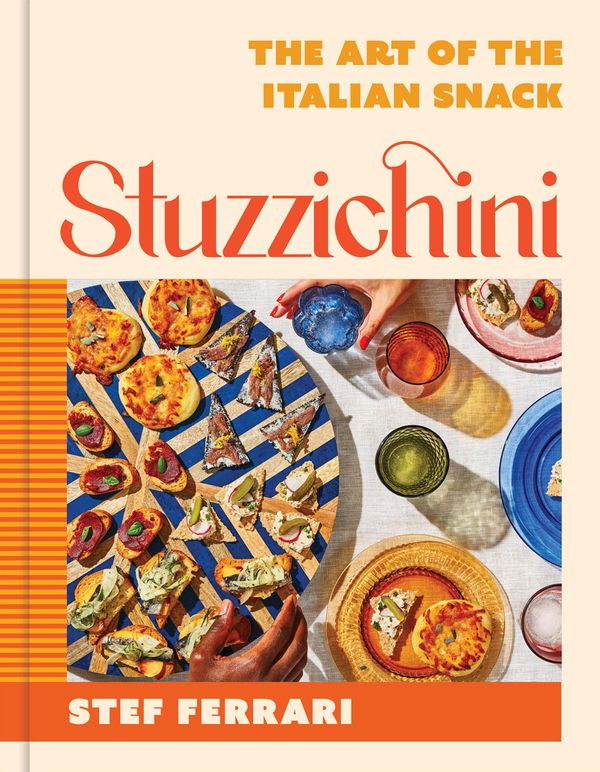

Two recent cookbooks which best capture the true essence and ethos of aperitivo culture are Anna Francese Gass's "Italian Snacking: Sweet and Savory Recipes for Every Hour of the Day" and Stef Ferrari's "Stuzzichini: The Art of the Italian Snack." Salon Food spoke with both Gass and Ferrari to get a bit more insight into the trend, its storied history and, of course, their favorite snacks.

"Italians have undoubtedly mastered the art of the snack,” Gass said. “Bites of food, eaten at designated times of day can be found from the tip to toe [into] the land of the boot. Moreover, the intersection of food and tradition are central to Italian culture. Most snacks are connected to a particular region with each of Italy’s regions having a distinct identity, not only in architecture but in gastronomy based on climate, geography and topography."

Gass jokes with me that Italian food runs in her veins — and she’s not exaggerating. Her grandmother worked as a lunch lady at her mom’s elementary school. Gass’ mother eventually became a banquet chef (with Gass helping alongside her eventually) while five of her aunts work in the industry, two as restaurant-owners in Italy and another as the head of a fine dining restaurant kitchen.

Ferrari similarly said Italian food is a key part of her genetic make-up. “This sounds trite at this point, but in true Italian-American style, some of my earliest memories are helping my nonna roll gnocchi down the tines of a fork,” she said. “It is truly in my blood.”

She was soon exposed to “proper Italian aperitivo” through her family.

After eventually moving to Florence in 2020, Ferrari sought community, as well as affordable dining options. “Going out to public spaces for a drink and finding myself swimming in complementary snacks was appealing for many reasons,” she said. “But once I started to dig into the culture and history, I was even more compelled.”

Obviously aperitivo drinks, like the perennially popular Aperol spritz, had gained huge traction in the United States and elsewhere globally, but Ferrari didn’t see this particular style of snacking growing along with it. “To me, it seemed like a missed opportunity since in Italy, you don’t have one without the other!” Ferrari said.

“When I began working in food more than 20 years ago, I tried to step away and learn other cuisines in the world and that’s been a big part of my career,” Ferrari explained. “But what feels most natural to me — and easiest to execute intuitively — always comes back to Italian.”

Gass’ book on Italian aperitivo culture is also deeply rooted in her family’s experiences.

"I started thinking how snacking, both sweet and savory, had been such a big part of my childhood,” Gass said. “I was born in Italy and came here at a young age. My mother maintained Italian traditions in our home and I was lucky enough to visit Italy regularly to spend time with our family."

She continued: "In Calabria, my grandmother was always baking taralli or preparing an antipasti platter. It wasn’t fancy but it was a constant and I loved it. Truly enjoying these moments more than lunch or dinner, I decided to take a deep dive into this cultural norm, region by region.”

For instance, there’s stuzzichini, which according to Ferrari is a derivative of the word for toothpick, stuzzicadenti.

“But I’ve also been told it relates to 'stuzzicare,' which means 'to tease,’ in this case, the appetite,” Ferrari said. “Regardless, the resulting word stuzzichini refers to the type of snacks you find served with aperitivo drinks. There are other names for these bites around the peninsula, too.”

Aperitivo culture doesn’t stop at savory snacks. Small sweet treats are on the menu, too.

"I find desserts to be too sweet here in the States,” Gass said. “I am not a fan of frosting or over-the-top desserts. That being said, when in Italy, I can’t stop eating dessert. Reason being, Italians really don’t rely on sugar for flavor. Desserts have a much more subdued sweetness with zests of lemon, orange, hints of vanilla, nuts, dark chocolate and fruits always shining through. [So] I really used that process and goal when developing these desserts."

Ferrari feels similarly.

“I’m a huge nerd about food,” she said. “Not only do I love to eat and experiment, but I’m really interested in understanding why and how something works. In the case of the green pea cannoli, you have the sweet, creamy filling, the salty, crisp shell, the earthy pistachios. And the Aperol nuts have this bittersweetness that is just so representative of Italian aperitivo in general.”

From their books, Gass names her Torta Tenerina and her Pizzette Delizia as two of the standouts from "Italian Snacking," while Ferrari highlights her Salvia Fritta Nella Birra (fried sage leaves), Cracker con Acchiughe, Cioccolato Fondente & Ricotta (dark chocolate, anchovy and ricotta crackers), as well as the classic roasted chestnuts.

Through their writing, both authors hope to offer readers a different look at Italisan cuisine, which can sometimes erroneously be discarded as heavy and homogeneous.

“Italian food gets cast as this single thing — very culturally flattened at times — and I cannot be more emphatic about its diversity and inventiveness,” Ferrari said. “It’s also, without ever being precious about it, extremely sound from a culinary construction standpoint. No one talks about hydration levels or the balance of acidity and fat, salt, umami, sweetness — all the elements that make a great dish. They just create things intuitively, based on seasonality and availability, and it works. Which is why there’s so much simplicity in the cuisine and yet it’s infinitely satisfying and craveable.”

I couldn’t agree more.

"At dinner, overindulgence doesn't happen because you don’t come to the table famished," she added.