A series of recent events in France have shown that younger generations are increasingly dissatisfied with current science programmes. During a graduation ceremony on May 10, a group of students from AgroParisTech, an institution specialised in agricultural sciences, called on their fellow students to abandon their studies in light of the current ecological crisis. The following day, in an opinion piece published in Le Monde, students from France’s Écoles Normales Supérieures voiced their concerns about science not meeting today’s challenges.

These and other initiatives show that while teaching students equations is still necessary, it’s no longer sufficient. Young people need to understand why studying science can help them tackle future crises, starting with the environment. To help, we need to teach them how to work as a group, create, put theory into context, and – even more challenging still – make them feel like they’re agents of change, and not just bystanders.

Many of our peers have already developed teaching methods to this end, but individual initiatives are not enough. We need to rethink entire curricula, seeking inspiration in pedagogical innovation and education science research, and work together at an institutional and disciplinary department level. In short, we need to form a community that can grasp the urgency of this critical challenge, and quickly.

The “anti-conference”

Nevertheless, a technical obstacle remains. When we come together as colleagues to discuss educational innovation, ironically, we opt for conventional meeting formats. I have lost count of the number of times I have given presentations on innovative and active learning – and doing so with a PowerPoint presentation, facing a silent audience.

I have been invited to endless working groups on innovation, where we all sit around a large table, as if we were in a meeting, with everyone discreetly checking their e-mails. When the format of these meetings is so fundamentally opposed to their content, these meccas of “innovation” rarely lead to new ideas.

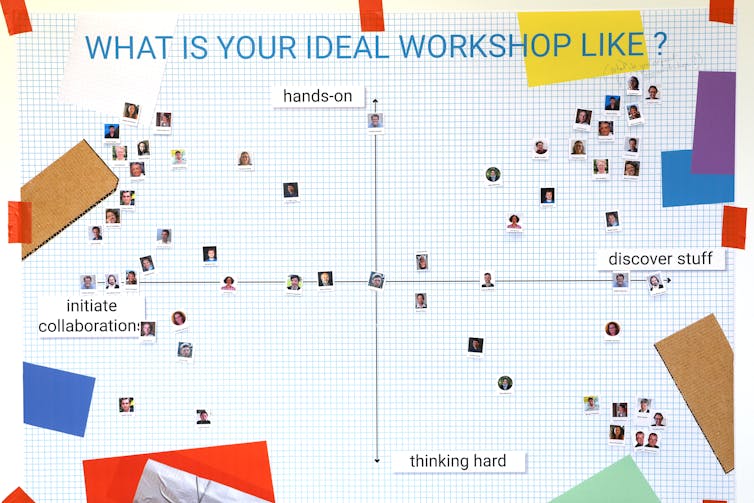

Wanting to organise a workshop to rethink the way we teach physics, this was the problem that my colleagues from Université Paris-Saclay and I faced. What setting could we offer participants so that they could come up with new teaching methods together?

To create something which avoids the shortcomings of conventional conferences, we decided to work with designers, something we already do for our outreach and teaching activities. Design is much more than mere decoration; it is also a way of imagining the construction of an event in all its forms. For this workshop, two designers helped us to develop the programme, come up with the activities and create a coherent graphic identity for the visual elements. They then helped us to carry out and film the event, before transforming it into a website to ensure the workshop’s sustainability.

To find the right workshop format, we decided to do the exact opposite of traditional conferences, as exemplified by the American Physical Society’s annual meeting. The meeting brings together some 10,000 physicists every year for five days in a large convention centre. The programme respects a certain military precision: 12 minutes per presentation, 10 presentations per session and 60 simultaneous sessions. In recent years, the event has become hybrid but ultimately, this format goes against what we are working to promote. So, we decided to create the exact opposite, step by step.

Instead of inviting a large number of participants, we limited ourselves to 30. Rather than a daylong series of speeches and posters, we had one presentation per day. Instead of a large convention centre, we were fortunate enough to use the spaces available at the Institut Pascal, which have been designed to host researchers so that they can work together collaboratively, with dedicated work and discussion areas, rather than conventional classrooms and auditoriums.

Instead of calling on some of the biggest names in education to inspire participants with impressive keynote speeches, we invited colleagues working directly in the field who lead innovation on their level, without necessarily trying to change the world. Denis Terwagne, a researcher from Brussels, develops teaching methods inspired by fab labs, bringing together students in Physics and Architecture. Claire Marrache, a researcher from Université Paris-Saclay, teaches a course on climate issues in which she asks her students to take measurements directly on the teaching building. Giovanni Organtini, from the University of Rome, uses low-cost tools like smartphones or Arduino boards to teach experimental physics. Fun Man Fung, a Singaporean chemist, uses a 360° camera to film live from the lab bench to show his students how to carry out an experiment. Rebecca Vieyra helps to share interactive simulations around the world.

Instead of a hybrid conference lasting a few days, we asked the participants to come for two weeks to attend the workshop in person. While this duration can be dissuasive and pose practical problems, it ensures active engagement throughout the entire workshop. Furthermore, in today’s current ecological context, it is increasingly difficult to justify round trips by plane for just a day or two. Lastly, this duration allowed us to come up with a programme built on two main parts.

Creating a community

Over the course of the first week, we organised a series of creative and intense activities. We wanted to help the participants to get to know each other, and show them that they could work together and develop new ideas in good spirit.

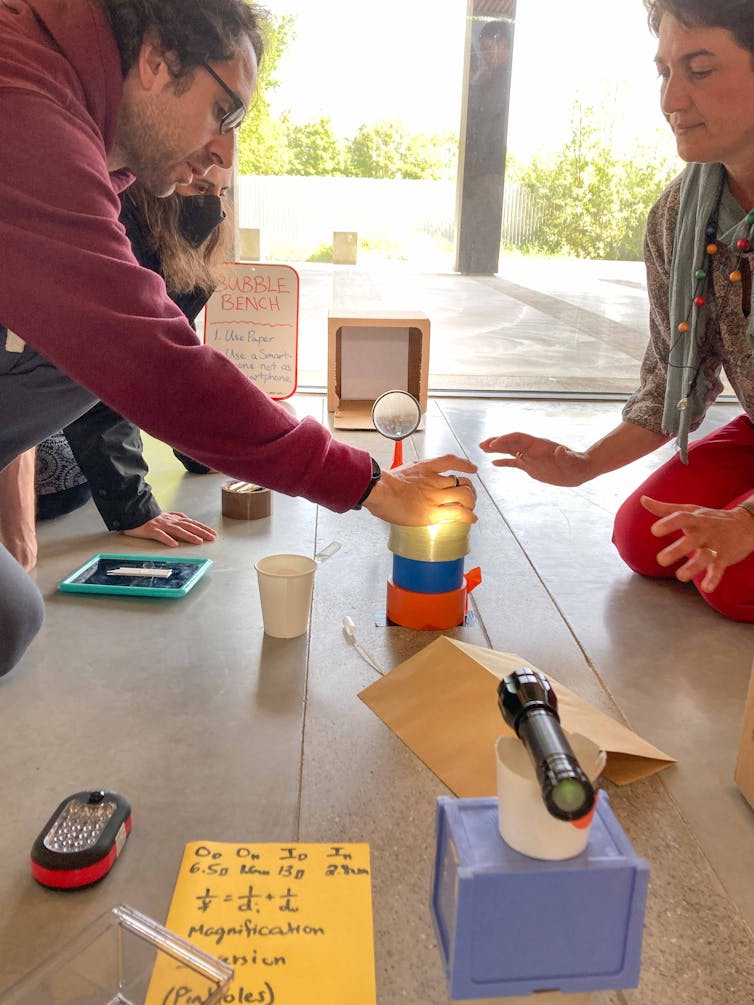

To do so, we provided them with fun and immersive Physics experiments. For example, we immersed them in a fictional world of espionage where they were asked to invent an egg protection device which would make as much noise as possible when dropped from a height of five metres. We also wanted colleagues to talk about their best practices. Instead of a series of presentations, we offered them new ways of exchanging and sharing.

For example, in the “snowball” setup, each participant explains his or her innovation to another participant, who takes notes on a dedicated sheet. Each pair then teams up with another pair to share and summarise their discussion. They then team up with another two pairs, and so forth. At the end of the workshop, the sheets are displayed in the form of a mini-exhibition, which everyone can view as they wish. In short, everyone has heard about each other’s innovations, and the sheets act as raw material for future workshops. We have also tested theatre, mime, and brainstorming sessions which end with a potential video, etc.

This first and intense part of the workshop helps to form a small professional and trusting community who are ready to innovate in the second part of the workshop.

Building and inventing together

For the second part of the workshop, we deliberately chose not to plan it. At the start of the second week, the participants developed the programme themselves. New ideas came flooding in by the dozens:

“Let’s think of how to teach a class in the local forest.”

“Let’s organise an Alcoholics Anonymous – style session where we share our problems as teachers and ask others to help us.”

“Let’s plan a ‘teach me anything’ morning, where we all teach each other something new.”

“Let’s come up with an international network to support education and innovation.”

We spent a wonderfully creative and liberating week together. Trusting one another and relaxed, we were able to create, research, think and even have fun together.

We spent a morning in the forest working on an immersive teaching method for our first-year students. We went to a cello concert combining physics and music. We learned how to use mime during educational breaks for lectures in auditoriums. We explored new teaching methods. In short, we felt that we had been innovative, or at least that we had been able to share and discuss productively.

All in all, we succeeded in providing approximately 30 researchers and lecturers with an inspiring and fruitful workshop. But is this enough to reinvent the way we teach? Certainly not, as we still need other colleagues, and more time to test, assess and consolidate. We also need institutional involvement and a more political perspective.

Ultimately, this mini-conference was a way of testing a new and more participative workshop format. This is why the dedicated website includes all of the content created during the event as well as the activity “recipes” so that colleagues can try them out. Certain ideas and activities can be redone and adapted to different contexts, even if less time is available. To put it simply, if you expect a group to come up with new ideas for educational innovation, a meeting or a brainstorming session with Post-its simply won’t do the trick.

Take the time to create the right format. Provide your colleagues with a creative environment and they will be more creative! Behind this truism lies perhaps one of the major challenges of change to come.

The author would like to thank the workshop’s organisers: Frédéric Bouquet (Université Paris-Saclay), Jeanne Parmentier (Institut Villebon-Georges Charpak), Fabienne Bernard (Institut d’Optique Graduate School) and the designers Lou-Andreas Etienne and Adèle Nyitrai. We also thank Katie Odowdall for the translation from French.

Julien Bobroff has received public funding from the Université Paris-Saclay, its Foundation and IDEX, the CNRS and the ANR.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.