On December 27, 1969, just a few days before the dawn of the new decade, the music world witnessed an extraordinary changing of the guard as Led Zeppelin II reached Number 1 on the Billboard charts, dethroning the Beatles’ final full-on studio effort, Abbey Road.

After hearing Zeppelin vocalist Robert Plant proclaim “I’m gonna give you every inch of my love” on their hit, Whole Lotta Love, the Beatles probably realized their days of singing sweet harmonies in an octopus’s garden were numbered.

And if the cover of Abbey Road is any evidence, the Fab Four apparently saw no other choice but to immediately vacate their recording studio and march, single file, into the streets of London, never to be heard from again.

Zeppelin would go on to dominate the sound and psyche of the ’70s. Their first four albums created templates for almost everything that was to follow in the next decade, including riff rock (Whole Lotta Love), heavy metal (Immigrant Song), prog (Dazed and Confused), power balladry (Stairway to Heaven), arena blooze (The Lemon Song), glam (Black Dog) and country rock (Bron-Yr-Aur-Stomp).

They even paved the way for late-’70s punk and the first Van Halen album. Guitarist Johnny Ramone once confessed that he honed his pioneering punk-rock skills by playing Zeppelin’s Communication Breakdown repeatedly. And Edward Van Halen told Guitar World in 2008 that, “I think I got the idea of tapping [while] watching Jimmy Page do his Heartbreaker solo back in 1971.”

But perhaps Led Zeppelin’s most important contribution to the ’70s was their fierce, uncompromising attitude. The band revolutionized the music industry when they negotiated their game-changing record deal with Atlantic Records that allowed guitarist Jimmy Page to produce their albums without any label interference. Additionally, the group retained control of all jacket artwork, press ads, publicity pictures and anything else related to their image.

As Page explained, “I wanted artistic control in a vise grip, because I knew exactly what I wanted to do.”

And what Zeppelin wanted to do was… everything and anything! They had this crazy notion that musicians should have the artistic freedom to play what they want — and that their fans might enjoy it. As it turned out, people did indeed love their wild experimentalism, and so did the record companies, who discovered they could make a ton of cash by allowing the band to have their own way.

Zeppelin’s example opened the floodgates to an intensely creative era that ushered in dozens of astonishing new genres of music, all played on adventurous FM radio stations.

Just a tiny sampling of the albums released in ’70s is enough to make any guitar nerd choke on their Ernie Balls – The Dark Side of the Moon, Sticky Fingers, Hotel California, Marquee Moon, Night at the Opera, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Van Halen, Never Mind the Bollocks Here’s the Sex Pistols, Machine Head – the mind boggles.

Given the vast scope of music made during the ’70s, trying to sum up guitar playing in the era is like attempting to solve a Rubik’s Cube blindfolded while riding a roller coaster in sequined bell-bottoms. It’s damn difficult! But let’s give it a shot…

The rise of heavy metal

You could argue that heavy metal was forged in the Sixties by bands like Cream, Jimi Hendrix, the Jeff Beck Group and, of course, Led Zeppelin. But you’d be wrong.

Sure, those bands started the ball rolling by chugging power chords through big-ass 100-watt Marshalls, but most of what they were playing was just amplified blues mixed with a bit o’ weird hippie psychedelia.

To make real heavy metal – 100 percent certified heavy metal – they were missing two ingredients: the devil… and Tony Iommi.

Hailing from the sooty factory town of Birmingham, England, Black Sabbath, featuring guitarist Iommi, along with vocalist Ozzy Osbourne, bassist Geezer Butler and drummer Bill Ward, set the world ablaze in 1970 with two groundbreaking albums, Black Sabbath and Paranoid. Their ominous riffs and occult-inspired lyrics on anthems like Iron Man, The Wizard and Electric Funeral would inspire thousands of bands, including Judas Priest, Van Halen, Slayer, Metallica and Ghost.

Given their preoccupation with the supernatural, it’s no surprise that their backstory reads like something out of Grimm’s Fairy Tales… but a whole lot grimmer. On the day Iommi was quitting his sheet metal factory job to become a full-time musician, catastrophe struck – he lost the tips of the middle and ring fingers of his right hand in a gruesome industrial accident.

A machine press came down and caught his fingers, and when he recoiled, the ends were ripped right off! (If there was ever a sentence that deserved an exclamation mark, it’s that one.)

However, Iommi wasn’t going to let a little thing like a couple of severed fingers stop him from playing guitar. Resourcefully, he used his machine-shop skills to custom-make special fingertip pads out of plastic and leather. Then, to make his guitar easier to play, he set his instrument’s action as low as it could go and detuned his strings to lessen the tension even further.

To Iommi’s surprise, when he plugged in his guitar into his Laney amp and cranked up his Dallas Rangemaster overdrive pedal, those elements coalesced into a deep, gut-rattling sound unlike anyone had heard before.

As Iommi later observed, “Some people believe the accident invented heavy metal, and it probably did. It helped me invent a new kind of music – a new sound and different style of playing.” He probably should’ve added, “But kids, don’t try this at home…”

Southern Harmony

Every action has an equal and opposite reaction, so while Black Sabbath were busy serving up doom and gloom in U.K. in 1970, the Allman Brothers Band were spreading good vibes and magic ’shrooms throughout the southern United States.

Traditionally, when you had two guitarists in a rock band, one played rhythm and the other played lead. Betts and Allman threw that playbook out the window

Formed in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1969, the Allman Brothers Band migrated to Macon, Georgia, where they began building a reputation for their incredible live shows that combined elements of rock, blues, jazz and country music into memorable songs and explosive improvisations.

Their exciting smorgasbord of influences was unlike anything audiences had ever heard, but what really made the six-piece band unique were the soaring, harmonized twin lead guitars of Duane Allman and Dickey Betts.

Traditionally, when you had two guitarists in a rock band, one played rhythm and the other played lead. Betts and Allman threw that playbook out the window, trading leads and orchestrating tight harmony parts similar to the way jazz horn sections worked together.

The concept wasn’t completely new. Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck briefly experimented with the idea when they were both in the Yardbirds in 1966, but Allman and Betts elevated their two-guitar attack into a brilliant artform – one that would influence and shape dozens of Southern bands like Lynyrd Skynyrd, Molly Hatchet, the Outlaws, 38 Special and the Marshall Tucker Band throughout the ’70s.

It helped that both Allman and Betts were terrific musicians with distinct sounds and approaches to their instruments. Allman brought a new level of virtuosity and aggression to the electric slide guitar that remains influential today, while Betts added a sophisticated sense of composition and melody to the duo.

Their landmark live album, At Fillmore East, released in July 1971, sent shockwaves through the guitar community. It not only changed the way blues and metal guitarists thought about two-guitar bands and improvisation, but it also influenced the sound of country music in ways that can be felt today.

The Allmans were primarily a U.S. phenomenon, but British blues rock legend Eric Clapton took notice. After seeing the Allmans play in Miami, Clapton was so blown away by Duane’s slide technique, he invited him to play an equal role on Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, one of the greatest albums of the ’70s and one of the most exciting blues rock albums of all time.

The Allman Brothers were unbelievable. Duane and Dickey Betts were in such harmony

Eric Clapton

“The Allman Brothers were unbelievable,” Clapton told journalist Sam Hare. “Duane and Dickey Betts were in such harmony. Their playing was very strong and well thought out. When Duane came to the studio [to play on Layla], I was so taken with him that I started ignoring my own band.

“I just tried to keep thinking of songs we’d both know so we could duet. We’d play blues standards like Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out and Key to the Highway. All these things were just really vehicles so we could play – just excuses to jam with one another.”

Tragically, on October 29, 1971, Duane Allman, then 24, was killed in a motorcycle accident. But despite the loss, the band miraculously carried on, recording their most commercially successful album, Brothers and Sisters.

Without Duane, guitarist Betts flourished, his sunburst Les Paul planting the seeds for modern country artists like Chris Stapleton, Eric Church, Lucinda Williams and the Zac Brown Band, all of whom have covered Allman songs in more recent years.

Just say Yes to prog rock

They say the best comedy is based on the truth, and that certainly goes for the one guitar joke that everybody knows:

Q: How many guitarists does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: One to screw it in and another dozen to say, “I could do that.”

Guitarists have always been competitive, and that was certainly true in the ’70s. It was no longer enough to write great songs and look good – you also had to have serious chops.

Musicians playing under the banner of “progressive rock” or simply “prog” turned technique into a religion, and the result was some of the strangest and most ambitious music to ever grace the Billboard Top 20 charts. The most interesting prog bands were King Crimson, ELP, Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull, Rush, Kansas, U.K. and Gentle Giant, but it was Yes who were the most commercially successful exponents.

Each member of Yes was an exceptional musician. Singer Jon Anderson – with his sweet tenor – had one of the most distinctive voices in rock; and virtuoso keyboardist Rick Wakeman – who wore sequined capes on stage – was flashy both visually and technically.

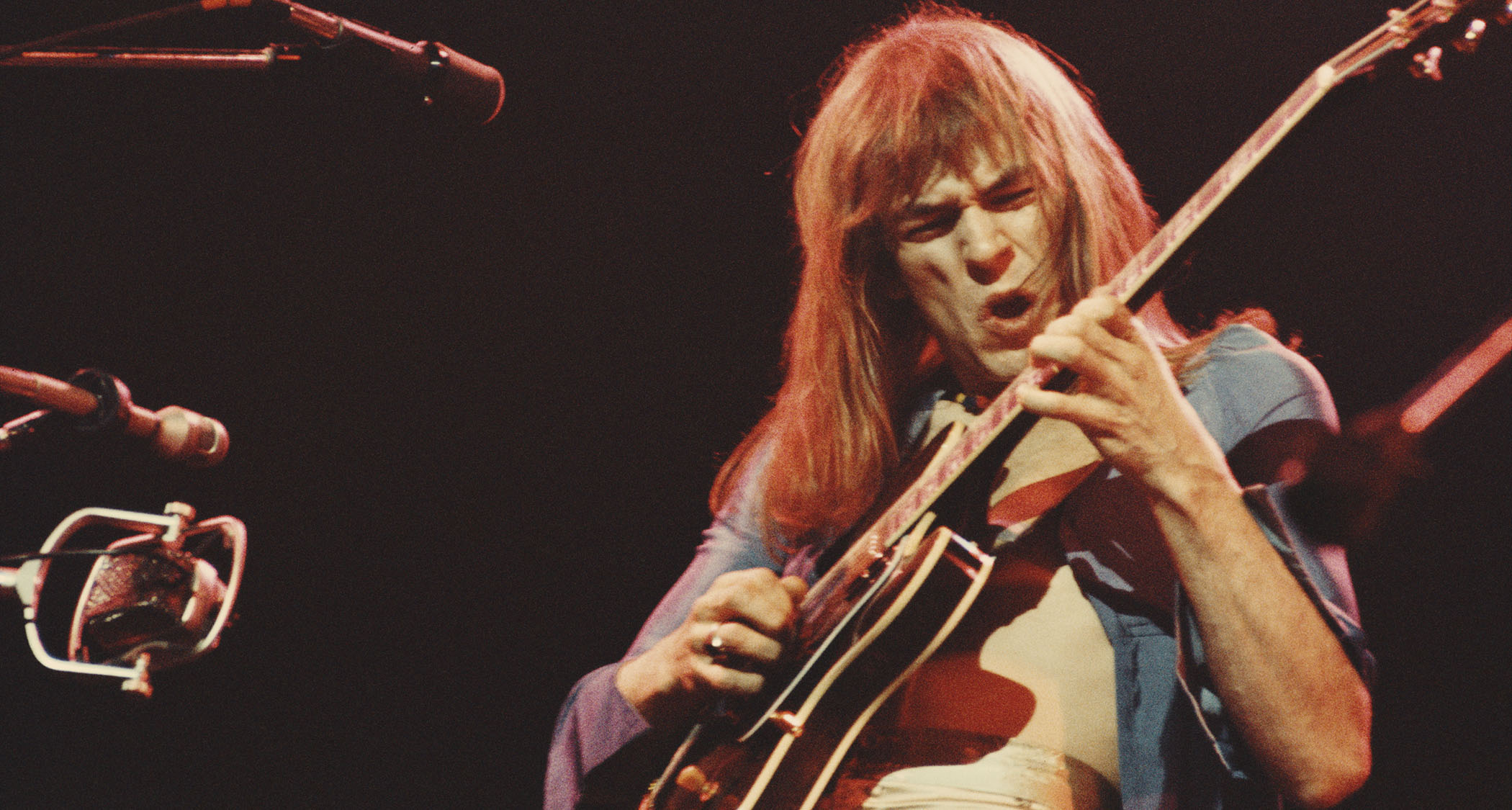

But the real star of the group was guitarist Steve Howe. Howe thrilled audiences by playing in a formidable assortment of styles on an astonishing array of electric, acoustic and steel guitars… often during the same song. Some critics accused him of being excessive, but for the most part, he was tasteful and generous, allowing his Yes compatriots to shine and take turns in the spotlight as evidenced by the band’s biggest hit, Roundabout.

During the band’s heyday, which lasted throughout the ’70s, his work on The Yes Album (1971), Fragile (1971), Close to the Edge (1972), Tales from Topographic Oceans (1973) and Relayer (1974) opened huge doors for guitar players looking to expand the techniques and colors they could use within a rock context.

Howe experimented with flamenco, Chet Atkins-style fingerpicking, classical harmonies and exotic chord voicings while shredding some of the speediest, harmonically advanced soloing ever heard on a rock album.

He was an amazing technician, but his lead playing also had an appealingly jagged edge that always kept the music rooted in rock ’n’ roll, no matter how complex it got.

Howe pushed the boundaries of popular music about as hard as any musician in the Seventies, and he did much of this on electric f-hole guitars like the Gibson ES-175, which was more associated with jazz players.

“The decision to buy the ES-175 set me on a course,” Howe said. “I didn’t consider myself to be someone who played solid bodied guitars at the time. It’s helped me to forge an identity as a guitarist with a full sound that isn’t reliant on distortion or tremolo or other gadgets.”

The decision to buy the ES-175 set me on a course... It’s helped me to forge an identity as a guitarist with a full sound that isn’t reliant on distortion or tremolo

Steve Howe

He was so dominant in the ’70s that he won “Best Overall Guitarist” in Guitar Player magazine an unprecedented five years in a row, influencing players as diverse as Alex Lifeson (Rush), John Petrucci (Dream Theater) and John Frusciante (Red Hot Chili Peppers). But unlike Jimmy Page or Eddie Van Halen, few people attempted to sound like him, probably because it was so difficult to do.

His lasting impact has been more about his grand concept than his style. He is the guy you can thank for introducing the idea of owning dozens of guitars for different colors and sounds. So, the next time anybody gives you shit for buying yet another Les Paul Junior or Epiphone Casino, just blame it on Steve.

Lighting the fusion

Guitarists like Howe, Frank Zappa, Tommy Bolin and Jeff Beck shaped the sound and style of Seventies rock by incorporating elements of jazz into their arsenal of licks. But just as significant were a new crop of young jazz players who started experimenting with the volume and aggression heard in rock music.

Guitarist Larry Coryell, sometimes called the “godfather of jazz-rock fusion” summed it up when he said, “We loved [jazz trumpeter] Miles Davis – but we also loved the Rolling Stones.”

Starting in the early ’70s, a gang of extraordinarily gifted young jazz shredders like Coryell, Pat Metheny, Al Di Meola and John Scofield scared the bejeezus out of rock’s greatest players with their command of the electric guitar. But the jazz shredder who made the most impact was the fast and furious John McLaughlin, who played a double-neck Gibson EDS-1275 through a 100-watt Marshall amp “in meltdown mode.”

Starting his career as a session musician in England, McLaughlin moved to the U.S. in the late ’60s, where he played with jazz drummer Tony Williams’ group Lifetime.

He then performed with the legendary Miles Davis on several pioneering electric jazz fusion albums, most notably In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew and Jack Johnson. But it was his work in the ferocious Mahavishnu Orchestra that made him a superstar in the rock world.

The five-piece Mahavishnu Orchestra combined elements of metal, jazz, funk and Indian classical music into their compositions, which they performed at lightning tempos. As Guitar World once put it, the band left you feeling as if they “were always on the very edge of exploding into a thousand pieces, so far did they push and extend themselves and each other.”

Guitar legend Jeff Beck was particularly floored. “Things took a funny turn for me in the early ’70s,” Beck recalled. “But it all turned out well after hearing John McLaughlin play on Miles Davis’ Jack Johnson album and with the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Every musician I knew was raving about him, and I thought, ‘I’ll have some of that.’ The mastery of his playing was unequaled.”

Soon after hearing McLaughlin, Beck turned down a spot in the Rolling Stones and began experimenting with his own jazz-rock band. He was warned that playing fusion was commercial suicide, but ironically, it resulted in his most commercially successful album, Blow by Blow, released in 1975.

In the early ’70s, the radical Mahavishnu Orchestra recorded two brilliant studio albums, The Inner Mounting Flame and Birds of Fire, and performed more than 500 shows, playing unlikely bills with straight-up rockers like Aerosmith, Blue Öyster Cult and the Eagles.

While many rock audiences were confused by their weird, explosive music, others were intrigued, catapulting 1973’s Birds of Fire to Number 15 in the Billboard charts. However, just as it looked as though they were about to achieve the impossible by bringing avant-garde, freak-out jazz to the masses, they imploded.

It was fantastic that we had popularity, but I think we had too much success too quickly. The band ended very acrimoniously, and that upsets me to this day

John McLaughlin

“It was fantastic that we had popularity, but I think we had too much success too quickly,” McLaughlin said. “The band ended very acrimoniously, and that upsets me to this day. I have great relationships with all the musicians I worked with. Except that bloody band.”

Despite their brief lifespan, Mahavishnu left a lasting mark. Not only did they influence classic rockers like Beck and Carlos Santana, but their albums have also inspired current avant-garde heroes like Guthrie Govan, Omar Rodriguez-Lopez (the Mars Volta) and Ben Weinman (Dillinger Escape Plan), proving that musical boundaries are meant to be shattered.

Glam bam, thank you, ma'am

While it was exciting that bands like the Allman Brothers and Yes were stretching the boundaries of popular music with their technical skills, many musicians were less than enthusiastic about prog. It was too damn complicated, and besides, who was going to piss off parents, disrupt social norms and have fun while looking cool? It didn’t take long to find out.

The answer came slinking out of Phoenix, Arizona, in 1971 when the Alice Cooper Band rose to fame with the hit single I’m Eighteen. Featuring a male singer with a woman’s name, the five-piece group were notorious for their theatrical stage shows, androgynous outfits and playing loud, obnoxious rock.

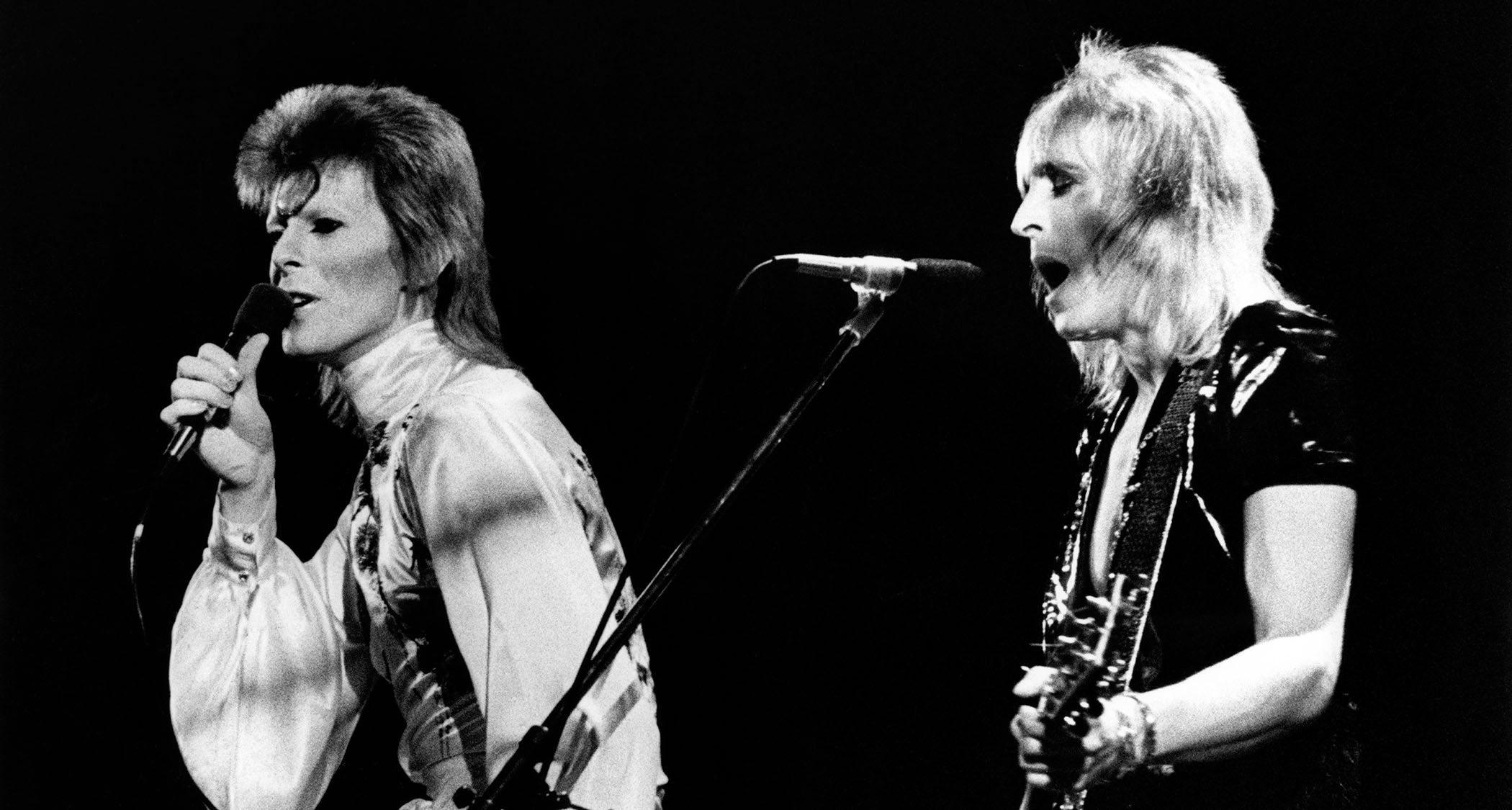

Boring old farts called them “degenerates,” but the press referred to them as “glam rock,” and it wasn’t long before the glitter craze took off, especially in England where David Bowie and the Spiders from Mars, T. Rex, Slade and Queen became mega-stars.

Glam was primarily about “the look,” but the bands also shared a common approach to their music. Unlike the progressive movement, glam rockers kept their songs tight, danceable and catchy. Instrumentally, their tunes were often powered by chunky heavy metal guitars and short, memorable guitar solos.

Mick Ronson, the iconic blond guitarist for David Bowie’s Spiders from Mars band, made no bones about being more interested in composing great riffs than diddling around with weird scales or playing 30 different guitars. Ronson believed if you wanted to play like John Coltrane or Mozart, go fuckin’ do it – but leave rock ’n’ roll out of it.

He had a point. It didn’t mean Ronno was a primitive musician. In fact, he was quite sophisticated. In addition to providing killer guitar parts to memorable rockers like Bowie’s Suffragette City, Panic in Detroit and Jean Genie, he was also a deft arranger, composing the dramatic orchestral parts on Bowie’s 1972 glam rock classic, Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

One sterling example of his artistry can be heard on the album’s classic, Moonage Daydream. He begins the song with a couple thunderous power chords, then slowly layers parts on his blonde 1968 Gibson Les Paul Custom through a half-cocked wah-wah pedal, until the song reaches a soaring, spiraling conclusion of ascending strings and tape-delay guitar.

While his parts aren’t particularly difficult to play, they are beautifully constructed, executed, and perfect for the song. In other words, totally rock and roll.

Ronson’s smart, economical playing (and glittering stage outfits!) helped create the template, not only for glam rock in the Seventies, but also Eighties hair metal. Ozzy Osbourne guitarists Randy Rhoads worshipped Ronson, meticulously imitating his look and use of a blonde Les Paul.

“Randy was a big fan,” said his brother, Kelle Rhoads. “That’s where his obsession with polka dots came from. He saw Mick Ronson with polka dot knee pads and Randy took it to another level.”

However, it would be wrong to imply that Ronson was the only influential glam guitarist in the ’70s. There were plenty of others including Johnny Thunders of the New York Dolls, Marc Bolan of T. Rex and Glen Buxton of the Alice Cooper Band. But perhaps the most famous and fairest of them all was Queen’s tall and elegant Brian May.

Queen have become so ubiquitous in our modern music culture that it’s easy to forget that in the ’70s they were originally a huge part of the same glam movement that spawned Bowie and the likes of Roxy Music and Sweet. But it might also be because Queen didn’t really sound like anybody else, and that was primarily due to May’s unique approach to playing and recording.

Far more ambitious than his fashionable contemporaries, his multi-layered guitar orchestrations on songs like Killer Queen and Bohemian Rhapsody ventured perilously close to being “prog.”

But May also knew how to boogie and always balanced his excesses with some good old-fashioned hard rock, as on We Will Rock You, Stone Cold Crazy and Keep Yourself Alive. Yes, Brian May could go over the top, but with Queen, he also knew when to kick royal ass – even while wearing flowing silk blouses and crushed velvet trousers.

Never mind the bollocks here's punk

Given how disheveled the typical punk rock musicians appeared with their ripped-up jeans and spiky hair, it was almost comical how much in they had in common with their glam rock counterparts. The Clash, Dead Boys and the Sex Pistols also believed that rock music should sound gritty, dangerous and close to the streets.

Punk guitarists didn’t just dislike progressive rock – they actively hated it. They were repulsed by what they perceived as the bourgeoisie snobbery of bands like Yes and Genesis. As for the Mahavishnu Orchestra… they couldn’t even pronounce it.

Punk musicians wanted to return rock and roll to its “everyman” fundamentals, so that anyone wanting to master three chords could take the stage and become a star. No one represented this attitude more singularly than the Ramones, a raucous four-piece juggernaut from New York City.

All members of the Ramones looked the same (shaggy hair with bangs), wore the same clothes (jeans, leather jackets and Converse All-Stars) and even shared the same surname.

Their songs all sorta sounded similar and their lyrics were hilariously moronic with titles like I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend and Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue. From a guitar perspective, it was the same story: every song consisted of an interchangeable series of power chords played with the same jack-hammer downstrokes by Johnny Ramone on his cheap Mosrite guitar.

On paper the Ramones sounded stupid and one-dimensional – and they were – but it’s also what made them great. They say the hardest thing about making great art is deciding on a direction and sticking with it. If that’s true, then the Ramones were the Picassos of punk.

They did one thing, and they did it incredibly well, and in concert, the band was as direct and as powerful as a locomotive. (I was tossed around so much during an out-of-control Ramones show that I lost one of my shoes after the third song and never saw it again.)

When the band were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002, it was said that their first album, Ramones (1976), saved rock from becoming “bloated and narcissistic.” While that’s not completely true – there was certainly plenty of bloat and narcissism to go around – they did provide a compelling alternative.

AOR in the USA

Punk wasn’t for everyone. But neither was metal, Southern rock, glam or any of the junk we’ve been talking about. That was the great thing about the ’70s. A lot of the music was kinda weird or extreme in some way. Even the biggest bands were odd when you really examined them closely.

That was the great thing about the Seventies. A lot of the music was kinda weird or extreme in some way. Even the biggest bands were odd

The Wall by Pink Floyd was psychotic. Stairway to Heaven by Led Zeppelin was fantastic, but totally wacky. And let’s not even get started on progressive bands like King Crimson and Jethro Tull.

Was there anything that was normal in the ’70s? Well, yes, there was plenty of meat and potatoes to be had. About halfway through the decade, many of the FM stations that were adventurous during the early part of the ’70s discovered they could grab more listeners and sell more advertising if the music they played was a little shorter and a bit more conventional. The stations shifted gears, and so did many rock bands who discovered they could sell more records if they did the same.

Suddenly, bands that appealed to more mainstream tastes started popping up like toadstools in Pennsylvania. Some called it “pop metal,” but most referred to it as Album Oriented Rock or AOR.

Platinum-selling bands like Foreigner, Journey, Boston, Styx, Eagles, REO Speedwagon, Steve Miller Band, Kiss, Toto, Pat Benatar, Kansas, Heart, Triumph, Bad Company and Fleetwood Mac were not particular innovative, but they wrote catchy songs that sounded great in the car.

While that might sound like an insult, it isn’t. Much of the music was very good and featured incredibly skilled guitarists like Neal Schon, Joe Walsh, Rick Nielsen, Ace Frehley, Steve Lukather and Gary Richrath, among others.

Now mix a bit of AOR with some Led Zeppelin, a bit of Pink Floyd and the more accessible “hits” of some of the more adventurous bands we’ve mentioned, and there you have the ’70s in a nutshell.

But wait… wait, wait, wait. What about Van fuckin’ Halen? Weren’t they part of the ’70s?

Well, the truth is – and this is highly classified information – that even though Van Halen’s first two albums came out in 1978 and 1979, they did not belong to the ’70s – they belonged to the ’80s. It was all a big mistake.

Eddie Van Halen insisted on arriving two years early, so he could gently guide guitarists to the next decade, where he would rule like a king for the next 10 years.

But you gotta promise not to tell anyone! If you do, I’ll deny everything. You know, conspiracy theorists, they’re all 5150…